By Hugh Morrison '26. The Museum of Modern Art and W. W. Norton & Company, Inc., New York, 1935.

Louis. Sullivan once expressed his architectural credo in the following terms: "Architecture is not merely an art, more or less well or more or less badly done, it is a social manifestation." Architecture was for him the study and expression of the social forces of a particular time and place, and the function of the architect was to produce buildings that would correspond to the most vital cultural needs of a people. The success with which Sullivan realized this high social purpose is pointed out by Lewis Mumford: "Sullivan was the first American architect to think consciously of his relations with civilization .... he knew what he was about, and what is more important, he knew what he ought to be about."

Professor Morrison's excellent study of the life and works of Louis Sullivan is thus in a very real sense a study of a movement, social as well as architectural in its broadest implications, in addition to being a study of a prophet and practitioner of this movement. Sullivan is best known to Chicagoans for his work on the great Auditorium unit, the scene of so many operatic triumphs before the brave days of Samuel Insull and his new opera house; for the magnificent Transportation Building at the World's Fair of 1893; and for his numerous creations in the otherwise prosaic field of commerce, such as the Marshall Field Wholesale Building and the Carson Pirie Scott store building, both of which are still sturdily fulfilling the function for which they were designed for over thirty years ago.

These buildings and the rest of the 134 structures of various types and functions with which Sullivan was closely identified either before or after the dissolution of the famous firm of Adler & Sullivan, are all strikingly illustrative of his fundamental belief in functionalism. Briefly stated, this architectural thesis is that "form follows function," that the architectural form should clearly express the utilitarian purpose of the building, the use to which it is to be put. Thus a railroad station should look like a railroad station and not' like a Roman bath, a library should look like a place to keep and read books and not like a Gothic cathedral, the facade of a bank building should not look like a Greek temple, and if the structure of an office building demands a blank wall, it should be left blank and not interspersed with a number of false windows for the sake of a specious symmetry.

The life of Louis Sullivan is thus the biography of an idea. Professor Morrison is to be congratulated for the painstaking care with which he has traced the evolution of this idea in the life and works of the master, and for his lucid interpretation of its theoretical foundations. The ultimate validity of this idea is apparent from even a casual glance at the work of the great contemporary European architects, whose efforts have the clean-cut, angular simplicity of line, the intimate fusion of form and function that Sullivan so consistently and so ably presaged. And finally, one of the most impressive characteristics of this book is its unusually attractive format, particularly the 87 plates which reproduce many of Sullivan's greatest buildings, the inclusion of which was made possible by the cooperation of the Museum of Modern Art.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Article

ArticleCURRICULUM VIVENS

March 1936 By E. Gordon Bill -

Article

ArticleHANOVER BROWSING

March 1936 By Herbert F. West '22 -

Class Notes

Class NotesClass of 1911

March 1936 By Nathaniel G. Burleigh -

Class Notes

Class NotesClass of 1910

March 1936 By Harold P. Hinman -

Article

ArticleAbout Twenty-Five Years Ago

March 1936 By Warde Wilkins '13 -

Class Notes

Class NotesClass of 1928

March 1936 By LeRoy C. Milliken

Francis E. Merrill '26

-

Sports

SportsHOCKEY

February 1946 By Francis E. Merrill '26 -

Sports

SportsTENNIS

May 1946 By Francis E. Merrill '26 -

Sports

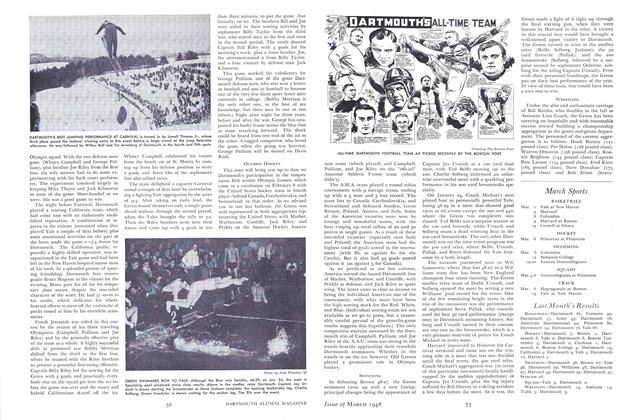

SportsOLYMPIC HOCKEY

March 1948 By Francis E. Merrill '26 -

Sports

SportsLEHIGH 16, DARTMOUTH 14

December 1950 By Francis E. Merrill '26 -

Article

ArticleBASKETBALL

January 1951 By Francis E. Merrill '26 -

Sports

SportsWith Big Green Teams

June 1951 By Francis E. Merrill '26

Books

-

Books

BooksPUBLICATIONS

May 1925 -

Books

BooksIT WAS FUN WHILE IT LASTED.

July 1960 By C.E. WIDMAYER '30 -

Books

BooksPRIVATE.

DECEMBER 1970 By HENRY B. WILLIAMS -

Books

BooksWALT WHITMAN RECONSIDERED.

December 1955 By KENNETH A. ROBINSON -

Books

BooksHOW TO CATCH A CROCODILE.

MARCH 1965 By R. J. B. -

Books

BooksTHE PROPHET OF CALVARY CHURCH

JUNE 1963 By Roy B. CHAMBERLIN