All the past, except that tiny part in pur memories, is peopled for us out of books. That is why we look at the past with either reverence or dislike, according to our temperaments. For the people that come to us out of books are rarely like live people, but only shades, not human, with qualities not ours. Books of history and biography have not often made their people like us, but more or less than us. And that is natural, for it provides the authors with an excuse for writing.

But Mr. Strachey and the large school of biographers who have followed him are attempting a different apologia for their writing. They say, in effect, "We will show you human beings as they were, which you will see is very much like what they are now. Our excuse for doing this is that the truth needs to be told, and even if you don't enjoy that truth we will make you enjoy our way of telling it."

Now this attempt with its justification is sometimes called "debunking," and in the temper of 1928-29 the term is reproachful. The tune of the time is "God Save Our Myths." And that is unfortunate, for surely not all the myths should be saved. No attempt at debunking seems able to hurt Lincoln, for instance, but it is probably healthy for us to learn that Queen Victoria was stupid and opinionated, or that Queen Elizabeth was not so much wise as lucky. For if these heroes are shown to have feet as muddy as ours, faults as crass, minds as uncertain, with how much more courage we can each look at both past and future, since we need no longer feel degenerate. Mr. Strachey, in short, is giving us boldness and high hearts for progress, for change, for aspiration.

Not that he tries to. He no doubt despises unthinking reverence or unthinking dislike of the people of the past, and the attitudes toward the present which spring from them, but he does not aim at their conversion. It is true, nevertheless, that his are heartening books, wise, witty, impartial yet sympathetic. In this book Queen Elizabeth remains a puzzling, incalculable creature, but mysterious only as everybody is mysterious. Strachey makes us know her, however puzzling. And not only her, but Robert Cecil, and Walter Raleigh, and Francis Bacon, and that strange semifeudal, semibarbarous England of the late Renaissance. But with Essex, somehow, he is not quite so successful. Perhaps Strachey can do best those persons who have minds definitely charactered, of clear colors, like Cardinal Manning's, or Victoria's, or Elizabeth's. Essex's mind was water, reflecting only the circumferential, without heat or light of its own.

And besides knowledge of its people, the book gives us the drama of high politics, which seems so farcical now, and the tragedy of one of history's strangest love affairs, which seems so real, and many, many, gentle smiles of wonder, both at our forefathers and at our- selves.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Lettter from the Editor

Lettter from the EditorEditorial Comment

February 1929 -

Article

ArticleThe Dartmouth Round Table

February 1929 By Leonard W. Doob '29 -

Article

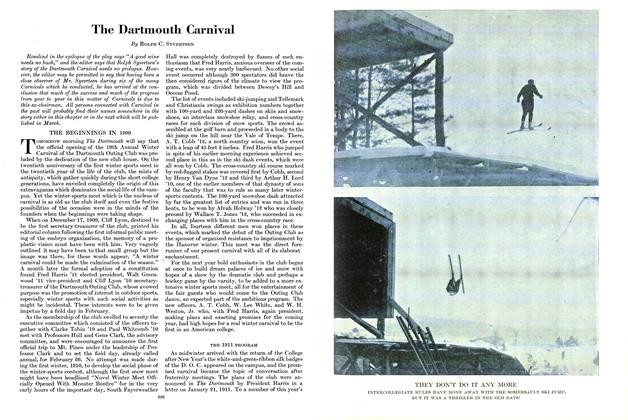

ArticleThe Dartmouth Carnival

February 1929 By Rolph C. Syvertsen -

Article

ArticleAn Umpire Talks!

February 1929 By Albert D. (Dolly) Stark -

Article

ArticleThe Story of an Indian

February 1929 By Samson Occom -

Class Notes

Class NotesCLASS OF 1923

February 1929 By Truman T. Metzel