For opinions which appear in these columns the Editors alone are responsible

HANOVER IN WINTER

THE human body is so constituted that it can endure without too much hardship rather marked degrees of heat and cold. This is especially fortunate in Dartmouth's case because in normal years the winter comes early and stays late. One harks back to the time when this fact was regarded as a liability. It is the more amazing, when one does so, to discover that in current conditions the Hanover winter is treated as an asset so conspicuous in its virtues as to constitute one of the chief reasons why many of the young men now in college saw fit to come thither.

If memory serves, the Dartmouth lutanists have not as yet taken up very seriously the praise of the out-door rigors, but doubtless they will. Our most notable laureate has hymned the gathering by the fire (pass the pipes, pass the bowl!) and extolled the situation of such as are snugly harbored before blazing logs, with various creature comforts suggestive of ease rather than of effort. Even Horace, beholding the snowy cone of distant Soracte, omitted to praise it save as a bit of beautiful scenery, inviting one to pile high the logs and call for another flagon of Falernian. Nous avons change toutcela. It pleases this modern age to go forth to grapple with winter at close grips and to discover that there is a zest in mastering the rigors of the northern cold. One appears to enjoy it—to a degree which some forty years ago would have been voted incomprehensible.

Hanover now enters on the time when, barring exceptional climatic conditions, one may expect a fair amount of snow and many days when the mercury ventures not to raise its head above the zero mark. Who cares? Who is going to seal his rooms hermetically and strive to counteract a temperature of 30 below outside with one of 80 degrees inside? The men of a generation or two ago, who boasted themselves as hardy Norsemen, usually did precisely that. It is these effete modern youths who swathe themselves in weird garments and set forth over the frozen wastes to ascend peaks which their fathers climbed—if at all—only in mild autumn weather and with much groaning of spirit, even then.

The Dartmouth of the Mauve Decade fancied itself as the abode of men with a lot of the bark on, mainly because there was no running water, and bathing was unfashionable. It endured the winter because it must. To rush out in joyous greeting when old Boreas came down from the polar cap was the thing it did everything else but, as the modern saying is. There was no Outing Club. Skis had been invented, but were used mainly by Scandinavians in Scandinavia. Snowshoes we had all heard of, but if there was a pair of them in Hanover they were virtually never seen. One cursed the cold, heaped coals on the fire and waited in such patience as one could for the dawn of spring. Nous avons change tout cela! The modern Hanoverian doesn't talk so much about how hardy he is—but he is a whole lot hardier than was his sire. He knows how to use the winter. It has become an advertisement for the College. It affords the excuse for one of the most alluring entertainments of the whole year—and one which few colleges outside those in Canada can emulate. The Carnival, to wit.

So here's to Hanover in winter! Is it not time some bard sang of something besides the frowsting in firelit rooms while the great white cold stalks abroad?

PUSHING IT DOWNWARD

SOME hopeful educator has been arguing within recent weeks for a pushing downward of collegiate education into the last two years of the high school, much as by resort to "junior high schools" the work of the high school has taken part of the time of the higher grammar grades. No doubt the idea is to get boys and girls ready for emergence from college after less than four years' residence—or perhaps to make possible a greater amplification of what is to be offered them in the four years. But it is unlikely this idea will go completely unchallenged, especially by those who have regarded the "junior high school" idea with scant favor and who would be predisposed to dislike the notion of a "junior college."

As the more complicated topics dealt with in higher ranges of schooling are pushed back into lower grades, it seems inevitable that there will be less and less time down there for rudimentary essentials. There is already much criticism of the schools for trying to do too much, and for turning out a product which, although it has cost much more than of old, isn't really any more serviceable for practical uses—possibly less serviceable than it used to be before we became so progressive in our pedagogical ideas. Before any such scheme as that advocated by the educator in question is adopted, it will unquestionably have to run the gauntlet of much opposition. It is the result, however, of the pressing de- mand for ending the educational period as early as posible, in order to let the newcomers get the sooner to the great job of living in the world, on their own. The twoyear college, letting its graduates into professional schools or out on the world at 20 or so, seems to be the idea. Our doubt relates to the possibility of compressing the lower grades so drastically.

NO "DEAREST ENEMY"

A PRINCETON man in speaking to the writer of this editorial said recently:"You people at Dartmouth don't know what it is to have one big game at the end of your schedule; one game with a traditional rival, which overshadows in importance all other games on your schedule." The man in question, experiencing a football season at Hanover, missed the "great day" of the football year, the acknowledged climax of the season, the game with the "dearest enemy." That game to a Princeton man is of course the Yale game.

Now in the early days of things, athletically speaking of course, Dartmouth did have one dearest rival. That rival was Amherst. The Amherst game did not always come definitely at the end of the season, and in some cases there were two football games a season with Amherst (in the days when training and coaching had not developed into a scientific system). Even as late as 1905, the Amherst game was considered a game of primary importance; for during the writer's sojourn at Dartmouth as a student, the Amherst football team defeated one of Dartmouth's best teams, and played a scoreless tie with another. One of those Amherst teams defeated Harvard also, and Columbia. But even at that date Amherst was turning more and more to Williams as her chief rival, if the turning had not come about before this, and was making the Williams game the most important on her schedule. It is possible of course that the Amherst-Williams rivalry, even from the beginning, was stronger than the Dartmouth-Amherst rivalry. It certainly was an old rivalry, but from the Dartmouth point of view it was essentially important that Amherst should be thoroughly beaten in sports each year in order to make that year a success. The Dartmouth rivalry with Williams was somehow a milder one, without the constant innate desire to overwhelm that college beneath "an avalanche of touchdowns."

Dartmouth's growth and expansion long ago carried her out of her old rivalries, and there was no other college with exactly the same experience in growth and development to become a natural chief antagonist. A few experimental rivals were dragged into the arena. For a few years men were told that the beating of Brown was the life purpose of every Dartmouth man. Brown games were always good games and exciting games, and the two colleges had begun to take each other seriously when there came a break in athletic relations that swept both away into other fields before a definite traditional rivalry had been built up.

Pennsylvania then appeared on the scene; but the colleges were too far apart and in different sections of the country, and the rivalry, when scarce begun, lapsed without either of the parties being deeply interested. In a wild attempt to find another "dearest enemy" for Dartmouth, someone suggested the Carlisle Indians; and one football game was played in New York in which the Carlisle Indians tore through a champion Dartmouth team (which had already beaten Princeton and Pennsylvania) in such a manner as to raise no question as to the superiority of the winning team but did nothing to create a new rivalry.

The long series now played with Cornell has engendered a feeling of the greatest regard and respect for that great university; but Cornell's traditional rival has always been Pennsylvania, and probably will so remain.

The Dartmouth games with Harvard, Yale, and Princeton have been in the past twenty-five years games of friendly contest without any element of traditional "dearest enemy" rivalry involved—save perhaps in the case of Harvard, where the game is "for the championship of Greater Boston" as a writer in the Globe put it some years ago. Dartmouth does her best to win, of course, in all such games and sends her cohorts to cheer on the teams when the games are within reasonable distance of Hanover. In the case of Pennsylvania and Cornell, the supporters have consisted for the most part of alumni, because of the loss of time to students in getting to the distant playing fields.

Meantime the fact remains that Dartmouth has no "dearest enemy" at present. Certain stress is put each year upon the winning of certain games, (not by the team nor coaches) which the undergraduates and alumni instinctively consider the most important. There is a psychological reason for this stress. In the past season one heard more talk about the Yale game "because Dartmouth has never beaten Yale in football." Four years ago the Cornell game carried the most importance, because of a series of Cornell victories. And yet despite this fact more men go to the Harvard game than to any other. Why? One answer is probably as good as another. The Harvard Stadium is a social unit that appeals. It in not so large as to prevent seeing the cheerers on the other side. The spirit is friendly, though the attitude is still that of country and mountain, toward the city with all its luxuries. There may also be some natural townand-country rivalry involved which may come to light with the new series with Columbia in New York.

But there is no Amherst-Williams, Harvard-Yale, Yale-Princeton, Exeter-Andover sort of game for Dartmouth. In the past, Dartmouth men have rather lamented the fact and have tried to create a rival by artificial stimuli. That has proved to be vain. The best attitude, it seems to the editors, is the natural one. Why must there be such a rival? Why not gain fame by being buried outside of Westminster Abbey, rather than in it? From the little perch up in New Hampshire the Indian teams come swooping down upon the cities, for better or worse, and -they always seem to win friends for themselves without any "dear enemy." Since there exists no natural athletic rivalry between Dartmouth and any other one institution, it is probably much better not to create any artificial status of that kind. Come one, come all,—from the opening of the schedule, when our oldest and very welcome visitor (Norwich) comes to Hanover, to the post-season game far afield with Washington, Georgia, Chicago or Northwestern,—each team we meet is a rival, worthy of our best efforts.

A REAL UNREALITY

THERE is a temptation probably felt by all editorial writers to attempt now and then the expression of a few thoughts on the reality of the unreal. No one, for example, has ever seen a meridian of longitude, or a parallel of latitude, save as a depiction on the map. These are "imaginary" lines and are wholly invisible, save where some ingenious builder has seen fit to trace in a thin line of metal on the pavement of some convenient building the meridian that runs through it—as one observes it done in the ancient church of Santa Maria degli Angeli in Rome. Boundaries between towns and states are for the most part incapable of being seen, yet what could we do without them? To the mariner threading trackless oceans, the imaginary line is the realest thing imaginable!

Not only that, but there are numerous characters m fiction of whose appearance one is far more positive than can be said to be the case with personages of genuine historical record. Mr. Pickwick would be recognized by thousands, to a single one who would know Francis Bacon if he walked into the room. The features of Mutt and Jeff are far more familiar to the multitude than are those of President Madison or President Polk. Our dates are based on more or less imaginary lines, also. In fine, the fact that a thing cannot be seen is not necessarily anything against it as a matter of reality.

It would be difficult, for example, to lay a finger on that intangible thing we usually call the "Dartmouth Spirit;" but it is probably one of the most valuable assets the College has at this moment, despite the fact that it is not carried on Treasurer Edgerton's books as worth a penny. It is the vital principle to which every kind of alumni activity refers. It is the thing which annually fructifies as an Alumni Fund. It is what draws us back in such multitudes to reunions. It is, in short, real. And may it be perpetual!

THE GAME AND THE TEAM

DESPITE the above heading, this is not to be a further discourse on athletic problems—supposed without much warrant to be all any alumnus ever thinks about—but is an effort to draw attention to the importance of maintaining at a maximum of efficiency the educational team with which the College plays a rather unexciting sport called the Curriculum.

It is one of our major problems at Dartmouth. We have a salary list which is somewhat lop-sided. It is liberal, so far as young instructors are concerned, and it draws to Hanover a most satisfactory list of aspiring young men who wish to take up college teaching as their career. It advances at stated intervals, as experience is acquired, and continues to be reasonably liberal, by contrast with what is paid elsewhere, until one gets into the upper ranges of professorial life. There it comes up against the competition of wealthier colleges and universities, which stand both ready and able to call away the splendid material which we have trained at the moment when it is becoming most valuable. It sometimes seems as if Dartmouth were running a sort of training camp, for other colleges to deplete of its best men as fast as they come along—a depletion which fortunately is sometimes resisted, by the exercise of personal sacrifice, so that our faculty continues to be sufficient for us. But it ought not to entail a sacrifice; and to that end the administration is working as Dartmouth grows in financial strength.

One has only to throw the mind back over past years —some of them not far past—to recall Dartmouth teachers of eminence enough to constitute both a source of pride and an inspiration to those who come after. Those best remembered by the current body of alumni would doubtless be John King Lord, Charles F. Richardson, Charles Darwin Adams, Herbert Darling Foster, Fred Parker Emery and several others, equally serviceable as inspiring teachers of young men, all affectionately remembered and in most cases blessed with nicknames which we all cherish reverently. What one has in mind is not a faculty with a few outstanding star performers, but a useful band of earnest and capable men of real standing in their departments, and above all with the ability to interest restive lads to learn; for be it well remembered, the boy who is interested can learn anything and will be eager to do so. The dumb-bell is usually, the student whose interest has never been awakened.

In fine, the methodological side of our problem, already carefully studied and well worked out, is the less important of the two. The men who carry out the methods are far more vital than the methods. The pity is that the men we train so admirably in our tradition and in our collegiate atmosphere not infrequently slip away from us when their capacities are at their fullest, because we cannot afford to hold them against the pull of others.

"JOURNALISM" AS A CAREER

THE reader probably knows that "journalism" is regarded in newspaper circles as a term of reproach —at all events no practicing newspaper man ever calls himself a "journalist" unless he is travelling in Europe. It is, nevertheless, an honorable word and a convenient one when properly used to designate the sort of work done by the men and women of the country who earn their bread and in some cases achieve a species of fame by writing for the newspapers. Hence its use as a caption for this article.

Is journalism a promising field for the college man? Yes—as promising as any we know of, and in some respects more promising than others because comparatively few seek it. The number of really well qualified workers in newspaperdom is at present smaller than the requirement, and a more general resort of collegetrained men to the profession would not be amiss. The demand exceeds the supply, and the tendency of alert newspaper managers to seek talented college graduates rather than less well educated assistants is increasing. To be sure the life is not an easy one and the rewards are not particularly alluring in a purely monetary way. Still it is a most interesting sort of life to atone for its hardships; and the compensation, while not glittering, is reasonably good for such as have the makings of a useful member of the fraternity in them. As in every such matter, something, if not everything, depends on the peculiar talents of the individual man. Newspaper work is exacting in its requirements both as to abilities and character; but as is true of every other line of human activity, it is hard to keep a good man down and the room at the top is abundant.

Thus far no school of journalism has quite taken the place, in the estimation of professionals, of actual training in the field by practical experience; but it would not be surprising if this situation changed as it long ago changed with respect to practitioners of law and medicine. In any case the work which can be done by young men in college as a practical preparation for the labors of a working "journalist" in after life is extremely valuable as a training. The thoroughly good newspaper man begins at the bottom and works his way up. Those whose incidental activities in college involve participation in making the undergraduate daily newspaper can find therein a training far superior to any that was open to their fathers and grandfathers.

In any event it would seem to be well for more students to consider newspaper work as a possible field for their endeavors after graduation. Despite the gentle pessimism of Mr. Ben Ames Williams's admirable story, Splendor, relating to the rise and decline of a laborer in the journalistic vineyard, the fact remains that it is at once an interesting and potentially important way in which to earn one's living, with adequate rewards for the truly deserving, and no worse failure than other professions exact of those who find they do not fit into the scheme of things.

DARTMOUTH WINS, APRIL, 1897 The last Harvard man is out with the score 4-3 in Dartmouth's favor; the Dartmouth team is running in from the field of play and the crowd is rushing to hoist the players on its shoulders.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Article

ArticleThe Dartmouth Round Table

February 1929 By Leonard W. Doob '29 -

Article

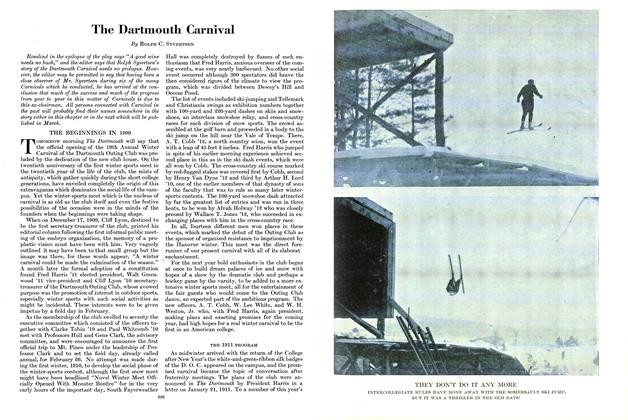

ArticleThe Dartmouth Carnival

February 1929 By Rolph C. Syvertsen -

Article

ArticleAn Umpire Talks!

February 1929 By Albert D. (Dolly) Stark -

Article

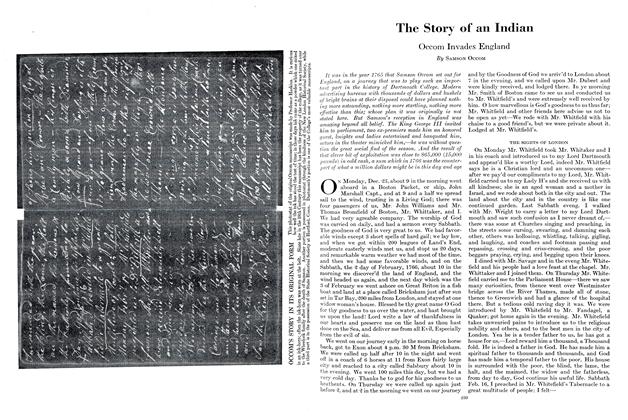

ArticleThe Story of an Indian

February 1929 By Samson Occom -

Class Notes

Class NotesCLASS OF 1923

February 1929 By Truman T. Metzel -

Class Notes

Class NotesCLASS OF 1927

February 1929 By Doane Arnold

Lettter from the Editor

-

Lettter from the Editor

Lettter from the EditorLetters

June 1933 -

Lettter from the Editor

Lettter from the EditorTo an old friend

NOVEMBER • 1985 By Douglas Greenwood -

Lettter from the Editor

Lettter from the Editor"Only Connect..."

MAY 1986 By Douglas Greenwood -

Lettter from the Editor

Lettter from the Editor'Round the Girdled Earth

December 1944 By H. F. W. -

Lettter from the Editor

Lettter from the EditorLetter from Geneva

May 1949 By MICHAEL J. DE SHERBININ '42 -

Lettter from the Editor

Lettter from the EditorA Magazine Makeover

Sept/Oct 2000 By Sean Plottner