The story of "liberalism" at Dartmouth since the War isan interesting one. With the College branded by ultra-conservatives, individually and collectively, as a hotbed ofradicalism but considered by the so-called "radicals" asmerely good ground for sowing their seeds of enlightenment,this article by The Round Table's president is of particularinterest. It gives a vivid picture of the activity of this under-graduate organization to further the liberal trend in theCollege.The Round Table is a flourishing institution with alarge and active membership made up of both students andmembers of the faculty. As Mr. Doob points out, it isthrough the generosity provided by the Class of 1879 Fundthat The Round Table is enabled to bring lecturers to Han-over.

A NUMBER of years ago when William Z. Foster spoke in Hanover in the midst of the red scare which infested the country, President Hopkins made what has since become a classic remark amongst liberals: "A friend of mine wrote to me some months ago that he would as soon have Lenin and Trotzky speak at Dartmouth as some of the speakers whom we were having there. I replied that if those responsible for a theory of government which now dominates an eighth of the earth's surface and a great host of her people were available for the explanation of their theories to the undergraduate body, I should be glad to have the students hear them and to have them form their judgment as to the dangers or merits of Bolshevism on the basis of direct evidence, rather than through the inconsistent and contradictory pronouncements of anti-Bolshevist propaganda."

This timely point of view was received with approbation by the country's intellectuals, although it may have caused some consternation in the mind of a shoe clerk or a salesman who had been accustomed to root for the Big Green football team. A former member of The Round Table used to say that due to this statement he came to Dartmouth as an undergraduate all the way from across the Mississippi.

The same attitude has characterized the work of The Round Table, Dartmouth's liberal club, during the past few years. The fundamental premise that men and wo- men should be invited to address the college who fulfill certain intellectual requirements regardless of the popularity or unpopularity of their points of view has been accepted by the organization. Other colleges usually have a rule to the effect that the speakers must, say, "conform to the accepted standards of good taste"— generally it can be discovered conveniently that a pacifist or a eugenicist violates the indefinitely defined term. And so it is a pleasant fact to recall that at Dartmouth through the courtesy of the Class of 1879 a sum of money is given to The Round Table to be used to secure any person at all: the administration exercises no restriction whatsoever. It is highly conceivable to find a man attacking the college and the system under which it operates and then receiving his expenses or honorarium directly from the bursar's office.

Constitutionally the purpose of The Round Table is stated as follows: "to bring about a fair and open-minded consideration of social, industrial, political and international questions by Dartmouth men. The organization shall espouse no creed or principle other than that of complete freedom of assembly and discussion. The ultimate aim will be to create among Dartmouth men an intelligent interest in the problems of the day."

Often The Round Table has been criticized for taking advantage of its absolute freedom by confining its activities to hearing the side of the liberal or the radical and not the conservative. The dean expressed it well when he warned us "not to make a half moon of The Round Table." There is truth to this and there are two possible answers. First, it is extremely difficult to secure the services of the men who are "dealing with hard facts and running society." Mr. Filene of Boston, who certainly is trying to enact reforms by improving present machinery, finds that he "cannot get away from his business." Mr. John D. Rockefeller Jr. is also too busy. On the other hand, a radical or a liberal usually jumps at the opportunity to address a group of college students for in most cases, his job resembles a missionary's: he must secure supporters to his cause. And, in the second place, in planning the speakers' program, the psychology of the audience that attends lectures in 103 Dartmouth has to be remembered: college students seek the sensational and only the radical in most cases can supply the novel flare.

Generally the guests of The Round Table address the members of the community for one hour. These meetings are public and of course no fee is required. Immediately afterward an open forum is conducted across campus in a comfortable room in Robinson Hall. Here long into the night The Round Table hears how the speaker personally has solved the world's problems—the social situation in which students and professors mingle, together with the solemnity of the late hour and the fame of the speaker and the smoke-filled room, generally has its effect on some intellectual processes. Sometimes the cool air the following morning restores the old habit systems; but often the ideas of the speaker become a permanent part of some personality.

Members in The Round Table for two or three years have been said to receive "a liberal education within the liberal college." Coming in contact with stimulating personalities is bound to have its effect. Unfairly it has been whispered abroad that The Round Table is a haven for student critics of our economic order. This can be denied categorically. At the same time it must be remembered that the opponent of some feature of the status quo is more likely to seek expression for his beliefs in the mechanics of the liberal club than the other type of undergraduate who assumes that whatever is must remain absolutely static. Only an ignorant person or one interestedly prejudiced will attribute to the many what a few isolated individuals happen to believe. Bluntly, then, the Industrial Defense Association notwithstanding, The Round Table is not on the pay roll of Moscow nor is every member a Bolshevik. Perhaps the easiest way to describe the activities of the organization is to mention some of its speakers within the past few years.

Clarence Darrow comes to mind. He is the patron saint of The Round Table although he is not aware of this position. Two years ago he talked on the new criminology of which he is one of the leading exponents. Students had to perch on the window sills to hear the old gentleman poke fun at people who imagine that man is more than a machine and responsible for his actions.

After the meeting, as Darrow was leaving the hall, an old woman approached him with a scrap of paper in her hand. Less than twenty years ago, Darrow's son, Paul, while a student in Hanover had been in an accident in which a relative of this woman had been killed. Paul was innocent of blame or even carelessness but as a slight compensation he promised to aid or to have his kin aid this family if ever the occasion arose. And now the woman's nephew had been accused of a crime and requested the elder Darrow's services. Darrow consented and took full charge of the case.

Last year, in late May, Darrow, who now has a nephew in the sophomore class, called us by telephone and announced that he "happened to be passing through Hanover and would like to talk to a few of the boys." I told a few, really a very few, to go over to our room in Robinson Hall. By the time Darrow reached the place, the room had overflowed with people who had been attracted by the rumor of the man's presence. We all moved over to the Little Theatre. He began by saying "You know my bag of tricks; so ask me whatever you want and I'll try to answer you." Two hours passed in this way. Then we persuaded him to give a public lecture the next day. "What shall I talk about?" "Oh, anything will do." "All right, let it be Tolstoy." He had been influenced by the sight of a Russian student who had been chatting with him. I assumed that the big lecture room in Tuck would be large enough, especially since the lecture conflicted with classes. But no, we had to go over to Webster. And there for an hour and a half Darrow used Tolstoy as a vehicle to carry his own kindly and impressive personality together with ideas on God, drink, crime, revolution, war, and so on. He had intended leaving town before noon, but he lingered on for another full day. In the evening, together with Paul and Paul's wife and daughters, he attended the Green Key show. He seemed to laugh a little ahead of the students. During the intermission he sucked a lollypop. . „

Darrow's opponent in the Scopes trial, the late William Jennings Bryan, came to Hanover five years ago. The boys greeted him cordially. Professor Rice of the Sociology Department measured the students' attitudes and discovered to everyone's surprise that the Great Commoner had had a great influence in raising some doubt about the theory of Evolution.

The successor to Bryan is John Roach Straton. He filled Webster Hall and the students applauded good naturedly as he pointed out again and again the inconsistencies and contradicting statements in Science. Members of the faculty, notably Professor Wright of the Philosophy Department, tried to disentangle the man by using reason, but Straton seemed to be a skilled dodger and so no one could convert him away from fundamentalist beliefs. As the meeting broke up around midnight, Straton asked for the courtesy of a prayer to God "since He has been neglected this evening." The prayer lasted fully five minutes and it contained a summary of the case against Modernism. A week later, the Associated Press reported that in a Southern town Straton had announced that Fundamentalism in this country is on the upgrade and cited as an example his reception at Dartmouth.

As an antidote to Straton, the arch mechanist, Frank Hankins of Smith College, was invited to present his radically different point of view. Dartmouth Hall was three quarters full—only a prof was speaking, you see, and a prof not a bit notorious at that. The discussion proved to be one of the most deeply involved of the year. Professors Urban, Mecklin, and Bowen criticized each other and Hankins. As ultimate reality was being rapidly approached, a member of the junior class arose and said seriously, "As a representative of the undergraduate body, may I be allowed to ask this question: If you don't define your terms, what's the use of all this Philosophy?"

This fall Scott Nearing answered the query, "Where is Civilization Going?" by pointing of course to what has happened to Russia. After the late war, Nearing began a tour of the colleges and was greeted in most places by a volley of objections and even abuse. To be sure, no such thing took place at Dartmouth. Another time, in 1926, Nearing again came to town. He had come from Clark University in Worcester where the president was said to have turned out the hall lights in the midst of Nearing's talk. On the Hanover platform, Nearing decided to illustrate a point by drawing a diagram on the blackboard. While turning on the blackboard lights, he happened to touch a loose wire and so blew the fuses of the entire building. For a moment he imagined he was the victim of the similar attack he had experienced the night before and, until the janitor was found, the honor of the College in this lecturer's eyes was quivering. This year, after his visit, Nearing wrote me to inquire quite quaintly about Dartmouth's disciple of Thoreau, "I noticed in the New York Times that one of your fellow students shook the dirt of darkness from his feet and headed for the woods."

Bertrand Russell, the British man of all knowledge (a modernistic poet, in reviewing Russell's book titled What I Believe, wrote that he couldn't understand how one man could believe so much), arrived in Rutland, Vermont, in the midst of the flood. The fifty mile drive across the mountains was filled with bumps and thrills. Usually the bridges had sunk below the eye level of the roadway and so on the approach it appeared as if the automobile were going to be plunged into the stream below. After a little practice, Mr. Russell caught on to this state of affairs. In his talk, by the way, he desscribed Science as a sociological phenomenon and said a word about a possible future world.

His wife, Dora, had been scheduled to address a group in the University of Wisconsin. At the last moment, President Glen Frank (a famed liberal, let it be recalled) decided that the best interests of the institution would be furthered by denying Mrs. Russell the right to speak before a college group in Madison. And so we of The Round Table telegraphed her and opened wide our gates. Owing to some excellent publicity in The Dartmouth, stressing Mrs. Russell's ideas on sex, Webster Hall was filled almost to capacity. Mrs. Russell is a short, attractive woman with a most appealing and quiet personality. Her audience was—well, simply charmed. "The difference between the American hypocrisy and the English is that in England you can say almost anything you want as long as you don't do it, while in American you can do almost anything you want as long as you don't say it." In the open forum after the lecture, Mrs. Russell described her new school and the original technique of teaching which she employs.

As a tribute to the political campaign, The Round Table conducted a symposium on October 9, at which representatives of the three major parties spoke. A ballot was given to the audience before and after the speeches. Hoover led by a large majority both times, but it was discovered that Thomas had gained the most supporters as a result of the evening and Hoover had lost a considerable number of votes. The speakers were James MacLafferty for Hoover, Harry Elmer Barnes for Smith, and Powers Hapgood for Thomas.

John Sumner, secretary of The New York Society for the Suppression of Vice, defended his own particular brand and method of censorship. Round Table members pounced on the gentle gentleman—one person asked him, in an attempt to delve into the center of the censorship business, "whether the so-called pornographic books that you confiscate are able to arouse you emotionally or sexually." And yet from New York he wrote, "It was a privilgee to be invited to speak before your organization." In December, Arthur Garfield Hays explained his own theory of suppression which is diametrically opposed to the one Sumner advocates. The same liberal point of view is true, in a less mild form, of Roger Baldwin, the director of The American Civil Liberties Union, who was able to attract over a hundred people to listen to him last spring, in spite of the competition of the beautiful May night.

Enough of these glimpses at the organization's speakers. It is hoped that the idea has been conveyed that The Round Table makes a sincere attempt to present what men consider "the sides" of questions of public importance; and at the same time to arouse sufficient interest in an undergraduate body which, since it is characteristically human, will only listen outside of the classroom to men and women who have interesting and well-known characters and who, if possible, choose a topic dealing with some form of the procreative process. In another phrase, we who run The Round Table try to be fair and we try to make extra-curricular education popular.

The Round Table as an undergraduate organization contains a mass of idealism. And so it often petitions governmental officials when it feels strongly on some public question. President Coolidge has been honored several times by a note from The Round Table; but strangely enough The Round Table has not been similarly honored by a note from President Coolidge. In the spring of last year, the club struck the liberal pose (sincerely or otherwise) and sent a telegram to the President and some Senators protesting against United States participation in the affairs of Nicaragua. Senator George H. Moses, a graduate of Dartmouth of course, made this concise and definite reply which ought to serve as a model for future action in Congress as far as directness of form is concerned: "I am in receipt of the night letter sent by you for The Round Table. I cannot follow you to your conclusions." However, the New Hampshire Senator was not quite so courteous this fall when he failed to reply to an invitation to defend Hoover in the political meeting—but then we know he was busy running the election.

The Round Table has achieved some recognition from the world that exists beyond White River Junction. The directors of the League for Industrial Democracy write, "The Dartmouth Round Table during the last few years has done valiant service in bringing the challenging questions of imperialism, of economic wastes and of social injustice to the attention of the thinking students of Dartmouth and in developing toward the problems of today, among at least a minority of the student body, the same kind of spirit as Lincoln and Garrison and Wendell Phillips exemplified toward the problems of their generation." It must be added again that The Round Table may have accomplished these things but that most important of all the organization as such supports no creed and is affiliated with no other organization. Individually, members may swing far to the left but The Round Table maintains its position at the ill-defined mid-point of controversy. Thus, due to the individual components, it is not surprising that people get the stereotype the writer from a well-known lecture bureau possesses in high-pressure business style: "I was very much astonished to learn that the Club, which as I understand it, is a liberal club, would not be interested in Mr. Max Eastman, who incidentally is one of the finest speakers available. This amazes me so much, that I would greatly appreciate a statement from you as to just what you would be interested in having." I suppose The Round Table was enshrined permanently in a proverbial Hall of Fame when it was included in that famous D. A. R. black-list.

This year The Round Table decided to extend its purpose of stimulating interest along political, economic and social lines by founding a magazine. The publication is. called The Tomahawk —this is a peculiar kind of instrument: it doesn't attempt to obtain people's scalps; rather it seeks to penetrate into the grey and white matter below and inject the virus of new ideas. It has come in conflict with no other publication on the campus. Professors have contributed articles: Shaw, Brown, and Richardson on various phases of the campaign; Speight on Civil Liberties; Haile on Coolidge's war and peace policy; Rose and Wright furnished book reviews in their respective fields of Sociology and Education. Outsiders like Scott Nearing and Harry Elmer Barnes have written for The Tomahawk. And, to be sure, there has been a response from talented undergraduates. Financially, the undertaking has been a difficult one. The printer's bill has to be paid for by the subscribers, the 134 students, the 46 professors, the 38 friends of those connected with the magazine, the 4 alumni (!), and George of the Campus Caf6. Hence, due to the scarcity of readers, advertisers haven't been too eager. And so the following greeting in the December issue, " The Tomahawk wishes all its friends and enemies a very Merry Christmas and a future more prosperous than its own."

LEONARD W. DOOB '29

ATTENTION 1907 Pride of the Faculty a few years ago. Left to right: P. H. Chase '07 M. K. Smith '07 Thacher Worthen 'o7,;Dorothy (Richardson) Lincoln, Margaret (Sherman) Neef, Sam Bartlett '07 Fanny (Hazen) Ames, Joe Worthen 'O9.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Lettter from the Editor

Lettter from the EditorEditorial Comment

February 1929 -

Article

ArticleThe Dartmouth Carnival

February 1929 By Rolph C. Syvertsen -

Article

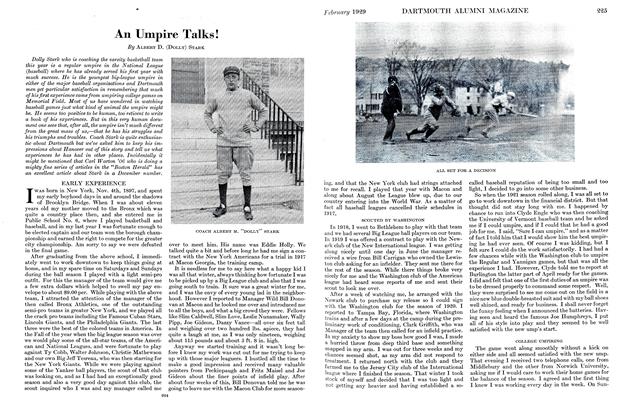

ArticleAn Umpire Talks!

February 1929 By Albert D. (Dolly) Stark -

Article

ArticleThe Story of an Indian

February 1929 By Samson Occom -

Class Notes

Class NotesCLASS OF 1923

February 1929 By Truman T. Metzel -

Class Notes

Class NotesCLASS OF 1927

February 1929 By Doane Arnold

Leonard W. Doob '29

Article

-

Article

ArticleLord Dartmouth Retires as Lord Lieutenant of Staffordshire

AUGUST, 1927 -

Article

ArticleTHE WEBSTER COTTAGE

MAY 1932 -

Article

ArticleMarch Enrollment

April 1946 -

Article

ArticleBrother's Helper

JANUARY 1959 -

Article

ArticleAfternoons With Frost

October 1973 By FIERMANJ. OBERMAYER '46 -

Article

ArticleClass of 1903

Mar/Apr 2006 By Stephen Eschenbach