By Alexander Laing. Doubleday, Doran & Company. $1.75.

Alexander Laing, of the class of '25, has published a book of verse to which, in memory of Housman, he has given the modest- if somewhat cynical—title Fool's Errand. The poems are reprinted from The Arts Anthology, Dartmouth, 1925, a little volume of Hanover Poems by Lattimore and Laing, and from periodicals including The Bookman, TheCentury, The Independent, Poetry, The Saturday Review of Literature, and others. The thirty-seven poems which Mr. Laing has gathered to make his booklet interest the present reviewer for two reasons: first, because of a very genuine personal liking for the author, and second, because the changing tone of this four or five years' poetic output suggests certain pertinent reflections.

A recent review of the book, though speaking in affable terms, did little more than note an obvious indebtedness to Housman. Now the indebtedness is there. Mr. Laing himself avers it. But, what is much more important, the later work shows an increasing independence, a more individual speaking voice, and a clear tendency to get out from under the pleasant but short-flighted cynicism with which Housman met the literary and philosophical confusions of the Nineties. In a time of shifting values, intelligent youth, if it is really hungry for truth, must first pass from doubt to cynicism, because cynicism is the most obvious defence of a sensitive and eager spirit. But if that spirit is eager enough, and strong enough, and backed by sufficient physical vitality, it must in time set out upon a reconstruction of its own. Not until this reconstruction is actively under way does this spirit—if it be articulate at all—begin to find its own voice. And we are forced to wonder whether at the present moment of confusions the finding of this voice is not being abnormally delayed

As for Mr. Laing, the reading and re-reading of these poems, in the light of what we know of their chronological sequence, convince us that he has sufficient desire and persistence, and sufficient spiritual and physical vitality, to push through to certain constructive patterns of his own,

"To crystallize the contour and the curve Of sudden music stirring in the brain."

"Mountain Moment," "Twenty-Second Spring," the sonnet beginning "There is a vale in Hanover," and the vigorous sonnet entitled "For an Educator," speak most personally to us of Dartmouth, but it is in "The Half-Remembered" and "The Coming of the Sun" that the surer voice begins to be articulate. Most of the poems in this little book are purely subjective—in intent if not in subject. That, of course, is to be expected in any young writer of the present day. When Mr. Laing has measured himself against an objective theme which demands an objective expression of a philosophy of life and demands it in a large way, we shall know better what he has it in him to do and be.

This present reviewer, judging by the hints in Fool's Errand, believes that Mr. Laing has the desire, has the keenness of mind, has the perseverance, and, above all, has the healthy vitality to continue the search until he finds something very genuinely worth crystallizing. For, as he suggests, only ". . .a spirit that has come to calm Through courage and the beauty of the world, Can aid its fellows, tangled in the charm Of fear."

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Lettter from the Editor

Lettter from the EditorEditorial Comment

February 1929 -

Article

ArticleThe Dartmouth Round Table

February 1929 By Leonard W. Doob '29 -

Article

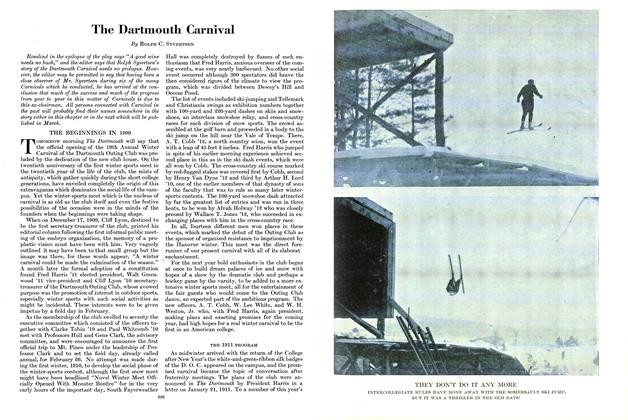

ArticleThe Dartmouth Carnival

February 1929 By Rolph C. Syvertsen -

Article

ArticleAn Umpire Talks!

February 1929 By Albert D. (Dolly) Stark -

Article

ArticleThe Story of an Indian

February 1929 By Samson Occom -

Class Notes

Class NotesCLASS OF 1923

February 1929 By Truman T. Metzel

David Lambuth

-

Article

ArticleANOTHER REPORT TO THE ALUMNI

May 1921 By DAVID LAMBUTH -

Books

BooksALUMNI PUBLICATIONS

March, 1924 By David Lambuth -

Books

BooksFACULTY PUBLICATIONS

March, 1924 By David Lambuth -

Books

BooksTHE DARTMOUTH MURDERS

January, 1930 By David Lambuth -

Books

BooksMAURICE HEWLETT: HISTORICAL ROMANCER

January 1939 By David Lambuth -

Article

ArticlePRINCIPLES OF COMPOSITION AND LITERATURE

December, 1914 By Robert Huntington, DAVID LAMBUTH

Books

-

Books

BooksFACULTY PUBLICATIONS

July 1920 -

Books

BooksA second edition, revised and enlarged

April 1931 -

Books

BooksEDUCATION FOR FREEDOM AND RESPONSIBILITY.

April 1953 By A. O. Davidson -

Books

BooksTHE THEORY OR RESONANCE AND ITS APPLICATIONS TO ORGANIC CHEMISTRY

May 1945 By Andrew J. Scarlett '10 -

Books

BooksCLINICAL TOXICOLOGY OF COMMERCIAL PRODUCTS. ACUTE POISONING (HOME AND FARM).

MARCH 1965 By Lours B. MATTHEWS JR. M.D. -

Books

BooksWords of Wisdom

MAY 1984 By Peter Smith