It is hard to imagine a reader who will not be fascinated - and probably horrified - by Merrill's tale of a brutal murder which occurred in Kentucky in 1811. Two men, Lilburne and Isham Lewis, apparently punished a slave named George for breaking a valuable pitcher by binding him and, in the presence of other slaves, dismembering him with an axe; they then partly destroyed evidence of their crime in the kitchen fire and buried the remains. The deed was revealed, however, when one tremor of the famous New Madrid earthquake, which first struck on the night of the murder, exposed George's unburned head. What gives this book its special interest, and its title, is the fact that the murderers were sons of Lucy Jefferson Lewis, a younger sister of Thomas Jefferson. And one detail which invites endless speculation is that Jefferson, who certainly knew of the crime, seems never to have made any comment on it.

Merrill's own interest in the case was aroused when, about ten years ago, he acquired a portion of the land on which this dreadful event took place. Eventually his research took him to archives and libraries all over the eastern United States, and he has now admirably reconstructed the crime and its attendant circumstances. He begins with the origins of the Lewis family in Virginia during the 17th century and leads us through a maze of intermarriages and business transactions, linking the Lewises with the Jeffersons and the Randolphs, to the time in 1807 when Colonel Charles Lewis, his inherited wealth lost, moved with his wife Lucy and his entire household to Livingston County in western Kentucky, there to seek a new fortune. Unhappily the Lewises succeeded no better in Kentucky than they had in Virginia, and the crime of Lilburne and Isham was only the last in a series of disasters which destroyed a onceproud family. Along the way to that terrible night of December 15, 1811, Merrill fills in with unrelenting, though always interesting detail a portrait of frontier life: river trade between Pittsburgh and New Orleans, business and real estate practices, law and justice, religion, social habits, military defense, farming methods, Indian relations, and, of course, slavery. There are five appendices containing genealogical information and various documents. No available evidence is omitted.

Yet finally serious gaps in the story remain, as Merrill readily admits. Because of conflicting accounts and lost documentation he is forced into speculation concerning such matters as the testimony presented to two grand juries, the accidental death of Lilburne in a bungled suicide pact with Isham, the ultimate fate of Isham (who escaped from jail before his trial), and even the exact location and manner of the murder. We, and Merrill, who is always careful to separate fact from opinion, are left with questions a scrupulous historian cannot answer - in particular questions about character and motive. For this reason I urge curious readers to supplement the historical truth of Jefferson'sNephews with the poetic truth of Robert Penn Warren's Brother to Dragons (1953), a version which freely enters the minds of the characters. Together these two books will remind us of Jefferson's apprehension concerning slavery: "Indeed I tremble for my country when I reflect that God is just."

JEFFERSON'S NEPHEWSBy Boynton Merrill Jr. '50Princeton, 1976. 462 pp. $16.50

Professor Terrie, a former chairman of theEnglish Department and associate dean of thefaculty, teaches a course in Colonial AmericanLiterature at the College.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureDinner for the Colonel

March 1977 By BRAVIG IMBS -

Feature

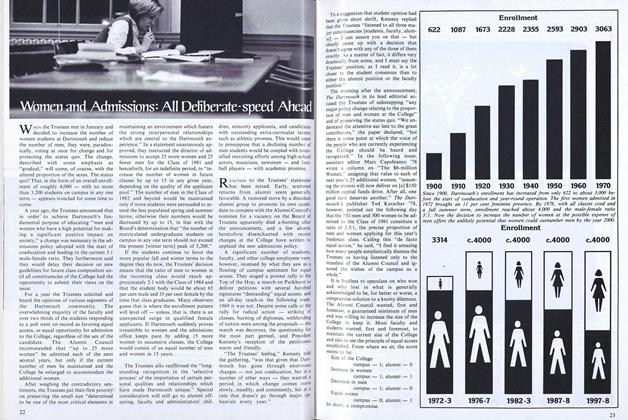

FeatureWomen and Admissions: All Deliberate-speed Ahead

March 1977 -

Feature

FeatureSleep-filled Days, Gambling Nights

March 1977 By BRAD W. BRINEGAR -

Feature

FeatureArtists

March 1977 -

Article

ArticleRambling with Melancholy

March 1977 By JACK DEGANGE -

Article

ArticleA Versatile, Admirable Teacher With "Every Feature of a Drill Sergeant'(sic)

March 1977 By S.G.

HENRY L. TERRIE JR.

Books

-

Books

BooksYOU HAVE TO PAY THE PRICE.

December 1960 By CLIFF JORDAN '45 -

Books

BooksCOLOMBIA: LA PRESENCIA PERMANENTE.

December 1961 By ELIAS L. RIVERS -

Books

BooksGOETHE AND MUSIC.

April 1955 By FRANK G. RYDER -

Books

BooksFIGHTING YANKEE.

March 1956 By GEORGE H. COLTON '35 -

Books

BooksSOCIAL PROBLEMS

December 1950 By ROBERT GUTMAN -

Books

BooksEARLY HOUSES OF NORWICH, VER

April 1938 By W. R. Waterman.