Dear Sir: In your February issue you printed a picture (taken in the spring of of "Dud" and his coach.

You mention by name several who are inside the coach and "McDevitt 'O7 and others on the roof."

Fat Pratt in the April issue names the balance of those inside and it might be of interest to know who the "others" on the roof are. They are all members of 'OB, freshmen at the time, and are from left to right, back row: Patton, Cowee and Frothingham; front row: Hale, Gomstock and Goodhart.

Very truly yours,

Allen Marble Co.Cleveland, OhioApril 8, 1932.

COMPROMISE

Dear Sir: "Why don't you write something about the change in heart at Dartmouth during the last 10 years? Write about the attitude of the athletes here today and you will find that an explanation of many of the losing teams." These words came from one of the well-known coaches lately, and he went on to say, "In general, only the fellows who are sure of making the team come out for the sport. That is something recent here, and that is one of the reasons why Dartmouth has been unsuccessful."

With this as a lead, an equally well-known sports writer drew up a case for the purpose of demonstrating what is happening to varsity sports at Dartmouth. Intramural sports, especially the interfraternity branch, he claims, are drawing the men who serve as scrub material for varsity teams. Going deeper, Jhe declares that "all the factions, the rivalry and dislike which has often cropped up in intercollegiate sport has its smaller counterpart in interfraternity sport." True intramural sport, he says, is best shown in the baseball department where pickup games are played every afternoon on Chase field. Other than that, intramural sports are for him nothing but cheap imitations of varsity sport. In closing, he makes a plea, not for the complete abolition of fraternity sport, but for more men to come out for the teams, and not only come out but stick with them. - And there we have one side of the question.

But it is a poor question, indeed, that has only one side. Let us look at the other side. Organized intramural sports, which have sprung into existence within the last six years, have as their objective the participation of as many men as possible in as many sports as can be handled. It is a well-recognized fact that prior to the birth of the intramural system most of the students partook of little exercise other than that required by the college system of recreational sport which covers the freshman and sophomore years. And this itself, due to the paucity of sports offered, was regarded as a nuisance. Students were glad to have it done and out of the way, after which the majority of them loafed physically. Then came the intramural department and, working hand in hand with the recreational department, it sought to bring about an interest in sports which would involve all classes. From a small thing it grew up, always promoting undergraduate interest and adding new sports to its schedule in order to gain more participants who might benefit thereby. For the sake of better health, for the sake of giving Dartmouth men the habit of sport and exercise, and for the sake of promoting a closer-knit undergraduate interest the intramural system was installed. That it has grown is undeniable. With a schedule that now embraces golf, tennis, touch football, basketball, hockey, winter sports, boxing, wrestling, handball, squash, swimming, track, and baseball the intramural department is in a position to care for the interests of practically the whole student body. In order to keep these sports alive it is necessary to have participants, and any undergraduate who is not a member of a varsity team is eligible to participate in intramural sports. Men who are signed up for a certain recreational sport receive credit for that sport if they happen to engage in an intramural activity for a dormitory or fraternity team.

Intramural sports offer distinctions as well as do varsity sports. Medals and cups are presented to the winners of the various activities which correspond to the letters given in varsity sports. Intramural sports do not require gruelling training regulations and the fact that any one but members of varsity teams may participate may, in a measure, lure away some of those scrubs who know they will show up to better advantage in the sports where there is less fierce competition for a berth, no training regulations, and a chance to get a little personal glory.

Thus far, the question has been a normal one with the usual two sides. This being true, there should be a middle ground somewhere on which it should be wiser to take a stand. There is no need for varsity and intramural sports to conflict. Men come to Dartmouth to gain something, but this should not be all of it. There should be a mutual exchange from which the College will benefit as well as the student. Cooperation is the word, and it should extend throughout all branches of the College. For the case in hand, then, why not co-operate? The varsity coaches know their men well enough to see which of them have possibilities. Let those men form the squad and permit the others to participate in intramural sports. On the other hand, if a man stands out as an exceptionally capable athlete in intramural sport, give him a try at the varsity. With this as a mutual understanding wouldn't conditions be altered so as to alleviate the situation? Those men who are definitely not of varsity stamp would be able to enjoy themselves in contests with others of a more equal skill and perhaps win a little personal glory. Those men who show ability sufficient to qualify them for varsity sports should remember that they owe something to the College—that they may bring credit to the College as well as to themselves. There is no need to tip the scales the one way or the other.

Kappa Sigma HouseHanover, N. H.April 11, 1932.

THE GERMAN PROFESSOR

Dear Sir: During the course of the past two years Germans have asked me very frequently about the college which I attended in America. They have been astonished when I have described the curriculum or the rules of the curriculum. Recently I have varied the story and have told them about the faculty of an American university or college. Their astonishment this time has been no greater than their ignorance. And so, to ascertain more accurately the cause of their astonishment and ignorance, I have gathered together some facts about their own faculty. I make the presumption, therefore, that the German university in this respect is not so well known and a short description and inadequate analysis will be of interest to readers of the ALUMNI MAGAZINE who may have a tendency to become so engrossed in Hitler that they forget the other changes occuring in German life.

A German who desires to enter the academic profession secures first of all his Doctor's degree. Then he prepares a careful piece of research, on the basis of the defense of which and through personal connections the faculty of a particular university may select him as an instructor. As an instructor he receives only the larger part of the special fees which the students pay who attend his lectures (and this amount is usually insignificant), but no salary. It is probable that he will remain an instructor for many years, until his professional (or personal) reputation has attracted the attention of the department of Education at the capital of one of the states; then, he may be called to fill a vacant chair at a particular university in this state, a position which gives him a relatively handsome salary and which he can retain until he desires to retire on a pension. Before he becomes a professor, he may be appointed from time to time special-professor, the salary of which varies. As a professor he has two other honors open to him: he may be called to teach in Berlin (and until recently such an honor carried and perhaps still does carry an enormous amount of prestige) or he may be elected president of his university for the usual one-year period.

From this short description it must be noted that the path leading from the instructorship to the professorship is long and difficult. Most instructors have been in their late forties or early fifties before they have secured promotion. And during this entire period an instructor has been receiving practically no salary. Hence it has been necessary that either he or his wife possess a private income. It is one of the axioms of German society that the professor has brought his family social respect and the wife the necessary money.

Why, then, has this educational system, which assumes that its teachers have their own sources of finance, been established? It seems to me that its founders were influenced by this liberal, pre-democratic point of view: the professors of a university must be men who are not working to support themselves but who are interested in their subjects per seas "pure" sciences or "pure" arts. This assumption has proven to be not entirely correct; for German professors, like all individuals, have been interested too in preserving the status quo which created their income or their wives' income. Consequently, German thought, which has been produced predominately by professors in universities, has been noticeably conservative (the word is used in no derisive sense, but indicates simply the bourgeois society in which the thought has been embedded; a wider explanation involves a history of German thought, which obviously cannot be attempted here) and nationalistic in nature. The social life of some of the German professors, furthermore, has been laden with the moral promiscuity which characterizes frequently the members of a wealthy and idle class; even students in a German university town may be aware of the more personal behavior of some members of the faculty. The other influence which has brought about a conservative tinge has been the bureaucracy through which a small group of men from an office desk in the Department of Education have been able to direct or certainly influence the entire intellectual life of a country.

And yet, here especially in Frankfurt where the university, founded in 1914, possesses on the whole only post-war traditions, the force of democracy is bringing about a change, even though the skeleton of the older system is still intact. Men from the lower economic classes are seeking to rise in the academic world and adaptations to accommodate them have resulted. A Ph.D., preparing his piece of research, may be given employment as the assistant to the professor under whom he is doing his work. The instructor may be called an assistant in a laboratory or a filing clerk or a personal secretary. The salaries from these minor positions are not large, but are sufficient to provide bare necessities. And the general unemployment situation drives many students to run the risk of the academic ladder, since the professor's salary and his prestige are actually so large. As instructors they may seek parallel positions with newspapers or with publishing houses. And these men may marry wives who at least can support themselves, if not their husbands. It is noticeable too that the increased attendance in German universities (no doubt also as a result of the unemployment situation) has created more professorial chairs and that the professors chosen to fill these positions are considerably younger than the men of the pre-war period. I must emphasize that this democratization is only a trend. New professors are not all dependent on their salary, but some do remain men who have risen accompanied by a fixed income. But the inflation and the whole economic and political situation in Germany have made these incomes less certain; so it can be expected that the democratic tendency will spread. It will be interesting, too, to observe whether correspondingly and relatively less conservative thinking in Germany results.

Frankfurt am MainMarch, 1932.

Dear Sir: I enjoyed the Undergraduate Number of the ALUMNI MAGAZINE SO much that I suggest that it become an annual feature.

April 15, 1932Chicago, Illinois.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Class Notes

Class NotesCLASS OF 1929

May 1932 By Frederick William andres -

Article

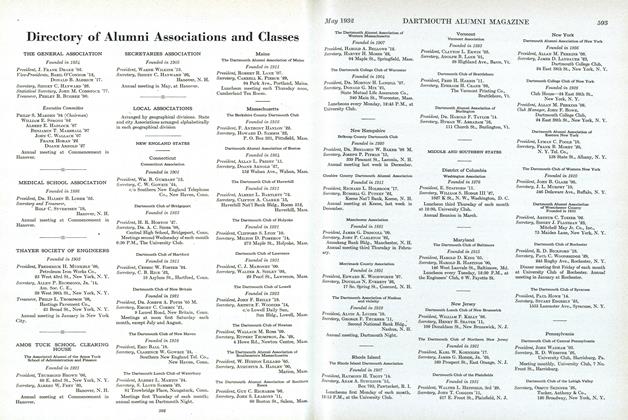

ArticleDirectory of Alumni Associations and Classes

May 1932 -

Lettter from the Editor

Lettter from the EditorPublic or Private Schools: A Letter to the Editor

May 1932 By Louis P. Benezet -

Article

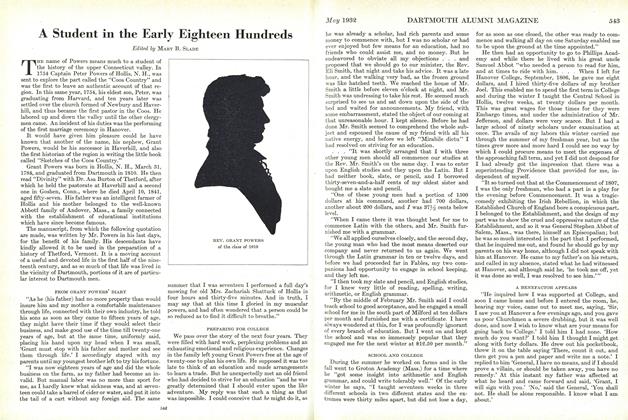

ArticleA Student in the Early Eighteen Hundreds

May 1932 By Mary B. Slade -

Class Notes

Class NotesCLASS OF 1905

May 1932 By Arthur E. McClary -

Article

ArticleLetch worth Village—A Home for Mental Defectives

May 1932 By Charles S. Little, M.D.

Letters to the Editor

-

Letters to the Editor

Letters to the EditorThe Dana Family

March 1936 -

Letters to the Editor

Letters to the EditorLetters

April 1943 -

Letters to the Editor

Letters to the EditorLetters to the Editor

November 1968 -

Letters to the Editor

Letters to the EditorMovers and Shakers

NOVEMBER 1993 -

Letters to the Editor

Letters to the EditorProfs and Scholars

SEPTEMBER 1998 -

Letters to the Editor

Letters to the EditorLetters

Mar/Apr 2007