For opinions which appear in these columns the Editors alone are responsible

THE ANNUAL RALLY

THE Alumni Fund this year presents two novel features. The campaign will start later, for all classes at once, than it has done in former years; and the total aimed at will be considerably greater. There will be fewer mailing pieces, also.

The idea of these changes may be worth discussing momentarily. The augmented total represents only the natural growth. The Alumni Fund has existed now for a series of years and has steadily advanced in total in order to keep pace with the growth and expansion of the College. It has been the frequent, indeed invariable, experience that a new and enhanced quota, though not always attained the first year, will surely be attained within a year or two thereafter. It is not long since it was felt to be a rather remarkable achievement to raise $90,000. Last year, with a quota of $115,000, the mark was overpassed and something like $120,000 was raised. This year the total asked is $130,000—not necessarily in the expectation that it will be fully attained on the first essay, but in the confidence that it will at least be approximated, and in the certainty that $128,000 for Dartmouth, though it would be short of the quota, would be far better for the College than $120,000 would be, if that had been adopted as the quota and actually attained. In other words, there is no magic in merely making your quota. The magic is in getting just as much as can be got for the proper support of Dartmouth's great and steadily growing work.

Shortening the time is the result of observation and experience. It is felt that just as good work can be done by concentrated effort as by more extended effort, and it is desirable to curtail, as far as can be done without forfeiture of real efficiency, the time devoted to this work. You may have noticed that a railroad engineer, after the locomotive has got under headway, pulls up his reverse-lever a few notches so as to shorten the stroke of the steam-valves and save steam. This is called shortening the cut-off and running expansively. It amounts to capitalizing the momentum already attained. Similarly, since our Fund has been going long enough to make it so well understood by all hands, it is felt that the need for long and proportionately more costly campaign has lessened.

We are going to make trial of it, at all events, and see. By every method that ingenuity can devise, it is proposed to cut down the overhead cost of collection which has never been excessive, but which is subject to curtailment—so that the College will get as near 100 cents out of every dollar contributed as circumstances will allow. The hope is to reduce the overhead to something like 5 per cent. Much below that it is manifestlyimpossible to go, but it is certainly needless in present circumstances to let the overhead approach 8 per cent. The reduction of the number of mailing pieces conduces to this same end; and of course the effort will be made as usual to ascertain at the outset just what proportion of our brotherhood will not respond at all, no matter how much literature is sent them, with a view to still further confining the expense and effort entailed.

In a word, more money than before is to be sought at a lower cost than ever before, and in a shorter time. It is possible to do that only because by this time the idea of the Alumni Fund has been "sold" to the entire body of our alumni, so that there is less need than in former years of devoting so much time to persuasions and explanations. How well it will work depends on the cordial cooperation and generous loyalty of our great and enthusiastic body of graduates and non-graduates, who retain a love and affection for the College.

That Dartmouth has become what it is today is due in no small part to the energy and generosity of its alumni. We balance our College books annually, instead of running in what the accountants so pictureesquely call "the red ink." The College budget is made with implicit, reliance on the Fund as a trustworthy asset, which will materialize as surely as if it were the coupon interest on a funded endowment. It has never failed in the past and it will not fail this year. In time we may, and probably shall, arrive at a point where this fund will be less vitally needed and can be cut down in scope; but that time is far off and is contingent on the accumulation of permanent principal endowments which as yet are not even on the horizon. The main thing is to keep the College running at its present glorious maximum of efficiency—the thing that we all get such a thrill out of and that makes us so proud of our heritage as Dartmouth men. To be permitted to assist in this work is a high privilege, as we see it, which most men welcome and cherish as a sort of decoration.

March—the collegiate month when the energy of student and teacher is likeliest to be at lowest ebb; winter has taken its toll of strength and spring hasn't quite arrived with a fresh supply. The lecturers have flown to southern climes, the basketball season is over,—swimming, fencing, gymnastics, and skiing have come to an end. There is mud underfoot and discontent in the air. Vacation comes just in time.

VAGABONDING IN EXCELSIS

WHAT are colloquially known as "vagabond" courses in the colleges appear to be obtaining a greater vogue than some of the older timers would be likely to relish. A "vagabond" course appears to be one which has no fixed orbit—a course open to students of exceptional ability, to pursue according to the student's own convenience and pleasure, without hard-and-fast oversight or requirements as to hours of study. Naturally such could be useful to none but men of pronounced ability, but the argument in favor of such arrangements appears to come from a much larger group than would be likely to be found available for such paradisiacal education.

The most conspicuous instance of adoption of this plan, transcending the "honors" work, which is fairly common now, is afforded by St. John's College at Annapolis, where, according to the prospectus sent out, it is proposed to make three extra-good students virtually the "guests of the college" during their senior year without dues and without specific duties, aside from the requirements that they must be residents at the College and must not contravene the laws of Maryland. These three senior fellowships are intended for men of exceptional intellectual promise. They are to pay no fees, attend no classes unless they desire, take no examinations and are as absolutely free to pursue the intellectual life at St. John's as young men can possibly be. At the end of the year they will receive their degrees, apparently without any investigation as to the use they have made of their year of freedom. Nor can the fellowship once granted be taken away save for the commission of a crime, or because the holder of the privilege is adjudged insane under the laws of the state.

Now whether this is or is not a good thing seems hardly to be the fit topic for any dogmatizing. It may be well to see how it works out among these Maryland Jonians. One reared in a sterner day may well feel some skepticism concerning the workability of such a system on any but the most restricted of scales. It is rather startling to think of seniors wandering unguarded in the groves of Academe and perfectly sure to get their degrees at the end of the year, no matter how they spend their time. Some of us, as has been remarked before, may well feel that we were born too soon for our own joy and comfort. One is accustomed to the idea that a degree must be justified by concrete evidence before the president and fellows will consent to part with it. But for the chosen, extra-special, ultra-intellectual few it may actually work well. Let us give St. John's a chance to prove it, insisting only that there be no mad rush to copy this extreme brand of academic freedom until it is shown to be useful, and remembering that after all it is confined to but three seniors who must have won their intellectual spurs so conspicuously as to command the admiration of their teachers.

One trembles, however, for the bodily and mental ease of these chartered libertines—possibly too harsh a name—when associating with the less fortunate mass of students who must still toil under taskmasters at the treadmill of education. Unless human nature has altered amazingly since very recent times, there may be some tendency toward wishing on such roving intellectuals nicknames expressive of mingled envy and dislike. To be thus enfranchised without losing the human touch may take a bit of doing. One must be worthy of this implicit trust and yet not become identified with the greasier form of grind. And yet, one must do a reasonable amount of grinding, else the powers-that-be may revoke the decree by which this academic leisure is created. As always there's the parlous channel to be traced between Scylla and Charybdis, with danger to either hand.

It appears to represent a revolt against "standardization and mechanization" of college work—these being regarded for some reason as sinful handicaps in an age worshipful of self-expression, individuality, and freedom from restraint. But is standardization really as bad as we are sometimes prone to think? Is individual freedom really as good as it can be made to seem? At all events it is rather refreshing to find academic freedom taken up as a matter affecting the student, and not confined to the liberty of professors to do something either daring or ridiculous.

However, there are notorious limits to the feasibility of making young men averaging 21 or 22 years of age absolutely free to browse among learned books without direction and without any assessment of their attainment thereby. Most boys aren't fit to be turned loose in this way—but note that St. John's doesn't claim that they are.

WHAT DO THEY EXPECT?

WHAT does the average business executive officer expect of the young men whom he takes on as associates and assistants in his business when they emerge from the colleges each year? It would doubtless be helpful if the young men thus initiated into active business life only knew what the exact standard was by which they are to be measured, but it is difficult indeed to purvey that information, even as a matter of averages. Notoriously some expect more than others. Some make due allowances for immaturity and inexperience, where others do not. Some are "easy bosses" and some very hard. One knows the breed that can penetrate the shell of shyness and perceive the makings of a useful man beneath, or that can estimate at its true, and usually meagre, worth the self-assurance of those gifted with an excessive fund of confidence. But just what is required of the young man fresh from college when he enters in an humble capacity (as a rule) the employment of some business concern?

One might safely sum it up in the rather meaningless formula, "his best." It remains to establish just what that "best" is and how good it must be to awaken the real interest of the men above in the possibilities of newcomers to the staff. It may be assumed that in order to interest the superiors one needs to be considerably above the common run of young men, more alert, more gifted with initiative—and yet not be so confoundedly full of initiative as to make the superiors feel that they are regarded almost as inferiors by this energetic neophyte. In these days of alluring advertisements in the magazines, there may be almost too much of the assertive young man who, thanks to a correspondence course, feels that he can talk himself over the heads of others into almost any exalted job in the office list. The wiser lad is probably the one who knows enough to be genuine, rather than thinly veneered. It is well to rise rapidly, provided one rises on intrinsic merit and can hold what one gains.

The know-it-all seldom makes good permanently-although one hastens to admit there are exceptions to all rules. The light that is hid under a bushel is sometimes discovered, although tradition holds that the chances are rather against it. Possibly it is best to lay emphasis on the familiar dictum, "Be yourself." The really important thing is to have it appear that being yourself is also being worth while.

A prolonged experience has led to the belief of the present writer that it is a mistake to assume most young men freshly graduated from college to be cock-sure, selfconfident prigs, inclined to patronize older and more experienced men, although that idea is industriously spread by the comic weeklies and by semi-jocular editorial writers. The average graduate in search of a job is likely to be reasonably modest, more scared than bumptious, sincerely anxious to please. Much depends on what the man has in his head, and on his genuine interest in the work he is given to do. Interest more and more seems to us the real passport to success, in college and after. The labor we delight in does more than physic pain. It leads to more intelligent labor, whether with hand or head.

There is more or less jesting in the public prints as to the expectation of newly fledged business men to become "executives" with all speed. It is natural enough that such aspire to become "executives"—but the climbing is likely to be slower than had been hoped and patience must usually be one of the characteristics of those who would attain. What the business executive expects of the newcomer to his force is much more important than what the newcomer expects of the business executive; and the really wise novice in an unfamiliar field will probably devote an alert observation to the task of finding out what is desired of him, with the idea of surpassing this, if possible, in Ways modest enough to avoid the deplorable sin of overdoing a good thing.

The college man, it may be added, is at present clearly preferred by enlightened captains of industry, and a good scholastic record usually counts for more than a shelf full of athletic trophies—fiction writers to the contrary notwithstanding. But there's no magic in a degree. The important thing is the man—his character, his capacity, his common sense, his readiness to assume responsibility at need, and at the same time his unwillingness to usurp responsibility without justification. "Be yourself" is probably the safest advice—and to make the "yourself" a thing to desire is the essential foundation.

ORGANIZED TEAM SUPPORT

THERE seems to be little doubt that in the development of incidental support for athletic teams, such as is implied in the custom of organized cheering and massed singers in the grandstands, the colleges of the United States are unique au monde. Whether or not the custom would be regarded as purely sportsmanlike in other countries is of no particular moment. Our American customs are our own, independently adopted, and have external application only in event we come to a situation in which such contests are international in character. Among ourselves there is no discernible revolt against cheers led by trained specialists in the art, save that there is of course a wholesome prejudice against employing the element of noise deliberately to distract or otherwise annoy the opposing players. The American habit of substituting players, in the absence of any injuries, for the purpose of meeting some transitory situation in the game has become so firmly rooted as to be pretty sure to abide, even though there is some grumbling against it on the ground that it exalts unduly the strategy of the professional bench and minimizes the prowess of the amateur eleven on the field. The British cannot understand our attitude—and don't have to.

The grotesqueness of organized noise along the sidelines is more readily apparent to older eyes and ears than to those of undergraduates, no doubt. Long custom has deprived the onlooker of either the disposition or the impulse to question the complete reasonableness of it, and indeed we should hesitate to say that organized cheering is in the least unreasonable. This may be because we are used to it, because most of us get a thrill from it, and because very probably it does put heart into the struggling players to hear the vast body of civilian supporters cheering it on to fresh deeds of derring-do. Most would hate to see the cheering, which has come to be such an important adjunct of every great college game, abandoned through the demands of ice-cold logic. It's part of the composite picture. The cheer-leaders don't feel so self-conscious as you might expect. One imagines that these young men actually value their jobs, and they are most certainly gifted in the art of timing the vociferations of several thousand people. The development of that art strikes us as being among the really notable things marking the progress of the past 40 years. The old-timers thought they knew something about the college "yell," but they didn't.

The real difficulty at the big games is that, being on your own side of the field, your own cheering doesn't sound so effective as does that of the opposition. Neither does the singing. With the bands it is a different matter because they are more nearly out in the open, and between the halves there is a chance to compare them. Here again is an amazing development, contrasted with what was known a generation ago. One with 30 years of graduate life behind him can recall when the college music was a very tame affair indeed, contrasted with the skilled modern band, mustering almost as many players as in elder days constituted a whole college class.

Away, then, with any carping spirit which would decry these picturesque concomitants of the athletic season ! It seems to us good to cheer and good to sing, with trained conductors to synchronize the artificial stimuli. Of course there is nothing spontaneous about it, compared with the unstudied shrieks that express the delight of a multitude when someone on the proper team gets loose from a scrimmage and tears 60 yards to a touchdown; but still it helps, and anyhow it is a recognized part of the consolidated spectacle which a big game presents.

This is more like a "Hanover Winter" than any we have had since 1917.

The new avenue with boulevard effect extending from the west steps of the Baker Library to the hill overlooking the river opens up a wholly new vista. It won't be long before that avenue is lined with dormitories.

Well here's to the Navy. Dartmouth had a navy of its own once but a freshet in the Connecticut washed it over Wilder Falls.

It seems too strange to be true that as late as even twenty-five years ago men "boarded themselves" at Dartmouth and lived off game such as rabbits and squirrels. Does anyone remember the smell of hedgehog soup in Thornton Hall? Men who board themselves are as scarce in this generation as were the "Chinaman's Steps" after the Dartmouth-Harvard football game of 1903. And yet there was a man in the class of 1927 at Dartmouth who built himself a little house on the West Lebanon road, connected it with electricity, boarded himself and lived alone in all his glory, except at such times as he entertained friends and members of his family. How many men of 1927 know that?

The ALUMNI MAGAZINE is always open to information concerning Dartmouth Men. It needs the smaller items for class news but it wants also longer stories of Dartmouth men who are engaged in any unusual or especially worthwhile enterprises. Any reader who can give us information leading to stories about, or pictures of, the work of Dartmouth alumni will earn our heartfelt gratitude.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Article

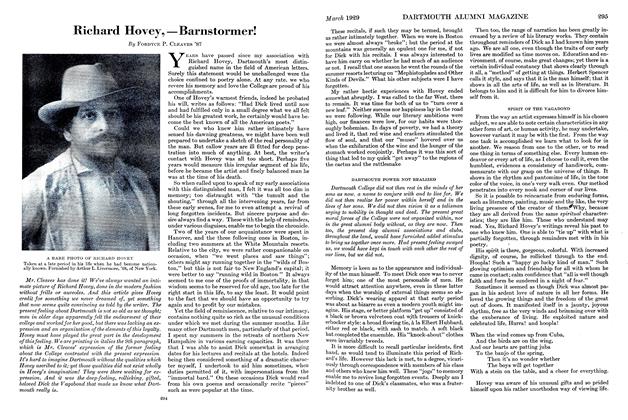

ArticleRichard Hovey,-Barnstormer!

March 1929 By Fordyce P. Cleaves '87 -

Article

ArticleThe Dartmouth Carnival

March 1929 By Rolf C. Syvertsen -

Class Notes

Class NotesCLASS OF 1927

March 1929 By Doane Arnold -

Class Notes

Class NotesCLASS OF 1914

March 1929 By John R. Burleigh -

Article

ArticleThe Story of an Indian

March 1929 By Samson Occom -

Class Notes

Class NotesCLASS OF 1898

March 1929 By H.Philip Patey

Lettter from the Editor

-

Lettter from the Editor

Lettter from the EditorEditorial Comment

November, 1930 -

Lettter from the Editor

Lettter from the EditorDartmouth Sea Dogs

March 1940 -

Lettter from the Editor

Lettter from the EditorLetters from Dartmouth Men in the Armed Forces

November 1943 -

Lettter from the Editor

Lettter from the EditorDouble Vision

MARCH • 1985 By Douglas Greenwood -

Lettter from the Editor

Lettter from the Editor'Round the Girdled Earth

April 1945 By H. F. W. -

Lettter from the Editor

Lettter from the EditorFrom the Editorial Board

Sept/Oct 2002 By Holly Sorensen '86