at one time Presiding Chief of the Abenaki Indians at St. Francis, Canada; now teacher in the Dartmouth school on the Reservation.

Of the two hundred or more Indians who attendedMoore's Charity School and Dartmouth College, not theleast notable was the group which came from Canada. TheCanadian regions had been travelled over by Wheelock'sexplorers and teachers as early as 1760, and an account ofthe travels may be found in the Narratives. Several Indian boys were brought to Dartmouth by two teachers justprevious to the Revolution, among them a member of thefamous Gill family which had its origins from a Deerfieldcaptive. Mr. Masta, who has taken up the Dartmouthsuccession of teachers on the Abenaki reservation (Dartmouth Indians having founded the school early in theNineteenth Century) writes for the ALUMNI MAGAZINE ashort account of these Indians who came to Dartmouth bycanoe or horseback in the early days. The first Masta cameto Dartmouth about 1809.

THE DARTMOUTH MEN

IN reference to the men of this place (St. Francis, Canada) who were educated at Dartmouth, I beg to mention: Francis Annance, Daniel Katnash (Cartnanch), George Annance, Phillip Gill, Joseph A. Masta, John B. Masta, Peter Paul Osunkhirhine, alias Masta, and Simon Annance, but I would lay stress especially upon the last two, because, while those did wonderfully well in their several spheres of activities, these gave the benefit of their education to their own people in their native land. Peter was a leader, and that also is the meaning of Osunkhirhine. He was the first Indian school teacher and minister of the Gospel here. He was about ninety years of age when he died and he had spent the first and best part of his life in teaching and evangelizing his own people. He was much interested in the education of all the young people of his tribe (Abenaki) but especially in that of his brothers Joseph and John Masta. He headed them to Dartmouth at Hanover, N. H., not so much by drawing along or going before as by instruction or counsel.

As the old saying goes: "An Indian is always ready when about to go on a journey" (because he has nothing to pack up)—what he wears on his back is all that he carries. As for the Mastas they each had only a white blanket coat and toque with hawthorn prongs instead of buttons. They covered the whole distance on foot and they were amazed at their good reception, even as if they were rich. Everybody was good and kind to them. The students supplied them with clothing and shoes. The poor Indians in return did everything in their power to show their thankfulness while the invisible proof therefor was in their hearts never to be forgotten.

While at school they were employed as boot-blacks, waiters, messengers, and jacks-of-all-trades. Simon Annance was the teacher of the protestant Indian school here for many years. I was one of his pupils when I was a little boy.

THE FAMILY HISTORY

I was born in 1853. At 12 years of age I was sent to a Church of England Missionary school at Sabrevois, P. Q., where my studies were all in French. The fact that I did not understand much, either in French or English, was a great drawback to my success. However I studied there five winters and was there and then given the option either to continue my studies at the Theological College attached to the University of Lenoxville, P. Q., or to leave the institution in order that some other young man might be trained in my stead for the ministry. I decided to leave, but was then offered to stay until spring provided I would teach two hours a day, to which I consented. In the fall of the same year I was appointed teacher of French at the Berthierville English Academy. In the spring of the following year I took charge of the St. Francis Protestant Indian School and kept it 10 years. In January of 1909 I was reappointed teacher of the same school and I am still at the desk. I have two children living, Mary Adelaide, and Alice. The former is in business for herself and the latter is a bookkeeper for the government department of Indian affairs, accountant's branch, Ottawa, Canada. She has held that position for the last fifteen years.

My mother's mother was Ursule Gill, and my father's mother Catherine Vassal. The Gills and Vassals intermarried. Samuel Gill and Miss James, two captives aged 14 and 10 years respectively, were brought here in 1711 from Gilltown, Mass. (according to reference to Mitchell's New General Atlas, County Map of Mass., Conn, and Rhode Island, 1864). The two captives were adopted by two women of the tribe as their own children and were treated with great kindness and affection. They soon picked up the Indian language, customs, manners. When they became of age to get married, the council decided that the two whites should be joined together in matrimony in order to preserve the pure blood of their race and accordingly they were married. They never, after or before their marriage, manifested a desire to return to their parents. They both died here at St. Francis, he in 1758, and she twenty years previously.

There are over a thousand descendants from this family.

Mr. Vassal who married an Indian woman of this tribe was a colonel of the Carignan regiment, and my grandmother Catherine Vassal must have been his granddaughter. Stanislaus Vassal, Catherine's own brother, married Felicite Gill, the sister of my grandmother, Ursule Gill.

HISTORY OF THE ABENAKI

Odanak is the name of the Abenaki Indian village in St. Francis Reservation, near Pierreville, Yamaska Co., Province of Quebec, Canada. Odana means a village or city. Odanak means to or from the village or city. This place was formerly known as the mission of St. Francis de Salles. Abenaki from Woban-a-ki means Eastern land; woban is east or dawn; a is at or to, and ki is land; wobanakiak is—the people whose land is toward the east in reference to that of some other tribes. The St. Francis Indians were also called Alsiguntegwiak meaning thosefrom the Oyster River. Als or els means oyster; alsi or elsi means of oyster; guntekw means river. Alsiguntekw means Oyster River, which is very likely Ellis River, Maine.

By the treaty of Utrecht the King of France ceded to England all the territories of the Abenakis tribes of Indians, his faithful allies. The governor de Vaudruil when asked if this was not true replied that the possessions of Abenakis were not mentioned in the cession of land. The Abenakis nevertheless were deprived of their lands and had to choose either extermination or expatriation. They of course chose the latter. They left hesitatingly and their departure from their native land was a sore, never forgotten, and to crown their misfortune as soon as they reached Canada, they were oppressed by the Algonquins who said:

"You are strangers. We do not want you here, and we will make a short story of you if you persist in occupying our land."

However they were allowed to stay a few days on trial and fortunately the two nations became friends in the meantime.

The first settlement of the Abenakis in Canada was at St. Joseph de Sillery near Quebec, the second at Chaudiere, and third and last at St. Francis.

Colonel Vassal married an Indian woman to whom were born two boys, George and Frank, and one girl Catherine. Catherine became the wife of Osunkhirhine to whom were born Peter, Louis and Mary. The husband died and his widow married Toussaint Masta, a Frenchman, whose children were Joseph, John, Adelaide, and Ignace. Peter Osunkhirhine, Joseph, and John Masta, Noel and Simon Annance, and a few others were educated at Dartmouth College, N. H. Peter Osunkhirhine became an ordained minister of the Congregational church and was the father of the protestant faith here. Joseph Masta was a physician; John Masta a surgeon; Noel Annance, a professor of languages; Simon Annance, a school teacher; I am the son of Ignace and am the present school teacher at Odanak. I have held that position many years.

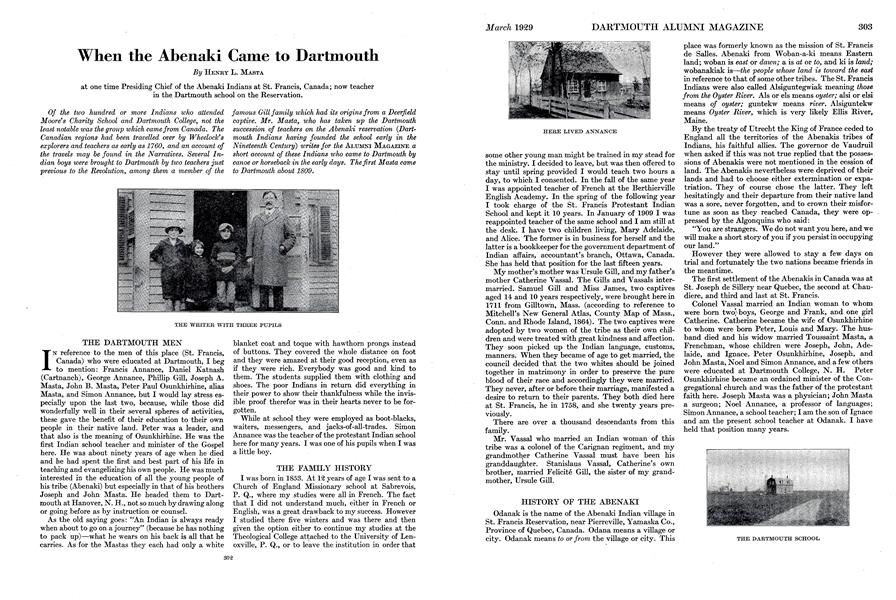

THE WRITER WITH THREE PUPILS

HERE LIVED ANNANCE

THE DARTMOUTH SCHOOL

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Article

ArticleRichard Hovey,-Barnstormer!

March 1929 By Fordyce P. Cleaves '87 -

Lettter from the Editor

Lettter from the EditorEditorial Comment

March 1929 -

Article

ArticleThe Dartmouth Carnival

March 1929 By Rolf C. Syvertsen -

Class Notes

Class NotesCLASS OF 1927

March 1929 By Doane Arnold -

Class Notes

Class NotesCLASS OF 1914

March 1929 By John R. Burleigh -

Article

ArticleThe Story of an Indian

March 1929 By Samson Occom