A man who in many ways might be the archetypical product of the Dartmouth fraternity system - affable, tanned, an ardent skier and tennis player, studiously casual in dress, mildly conservative - has called for the abolition of fraternities and sororities at Dartmouth. He is James Epperson, professor of English at the College since 1964. His complaint is against the "disturbing and barbaric values" of the fraternities and sororities, and he has petitioned the faculty to discuss the abolition issue at a meeting next month.

In the past few years the fraternities have come under increasing criticism for public rowdiness, the slovenly, decayed condition of their houses, and what Epperson terms "drunkenness, arrogance, intolerance of people with different values, and the willingness to humiliate defenseless people - they stand against everything the College teaches." Alumni who have sat near house blocks at football or hockey games and who have seen the Sunday morning carnage on Webster Avenue voice similar indictments.

For their part, the fraternities have protested that as virtually the only social centers on the campus they are subject to depredations by outsiders, that they suffer from insufficient financing and are generally blamed for the misdeeds of all students.

The bare-knuckle challenge of "abolish the fraternities" might have been issued for its shock value. Epperson, who remembers his own fraternity days at western schools with fondness, says that while at times he despairs of any possibility for improvement he also harbors an occasional hope the fraternities "can reorganize and get back into the world." It is possible that a faculty debate and the threat of an abolition resolution forwarded to the Trustees might generate reforms and justify Epperson's moments of guarded optimism. "Perhaps this action," he says, "will convince [the fraternity] people we live in a society together."

The petition, which was signed by 25 of Epperson's faculty colleagues after most of the students went away for the summer, caught the fraternities and sororities off guard. It followed a spring of acrimonious debate over the adoption of a fraternity constitution ("An Unease on Webster Avenue," April issue) designed to formulate basic mutual responsibilities and obligations on the part of College and the 23 houses.' Fraternity resistance boiled down to fears of a take-over by the College, but the constitution, which established a fraternity board of overseers with several alumni members (including a Trustee), could turn out to be their best friend. During the summer, Epperson talked at meetings of the Interfraternity Council and one of the fraternities. He characterized the discussions as "somber but constructive."

In a report commissioned by President Hopkins in the mid-19305, the Dartmouth fraternities were described as being "notoriously reluctant to exert positive group pressure towards the enforcement of minimum standards of conduct." Then as now the houses were plagued by financial difficulties. Then the war came and the issue was dropped. Today, the fraternities count about 50 per cent of the male undergraduates (and a few females) as members, and of the 1,200 women students 150 belong to one or the other of two sororities. The members almost universally praise the close friendships they develop among their brothers and sisters, but according to Epperson there also are voices within the houses urging shape up or face dissolution.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

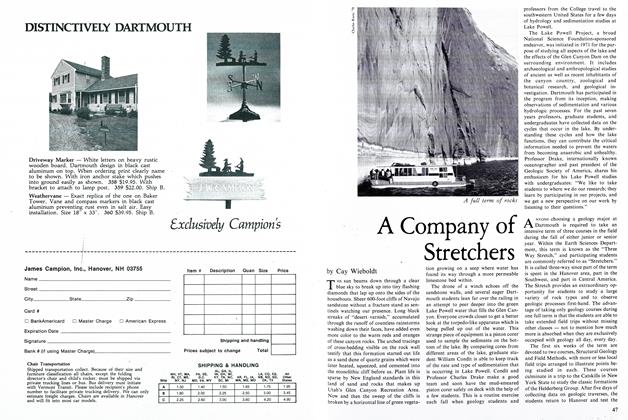

FeatureA Company of Stretchers

September 1978 By Cay Wieboldt -

Feature

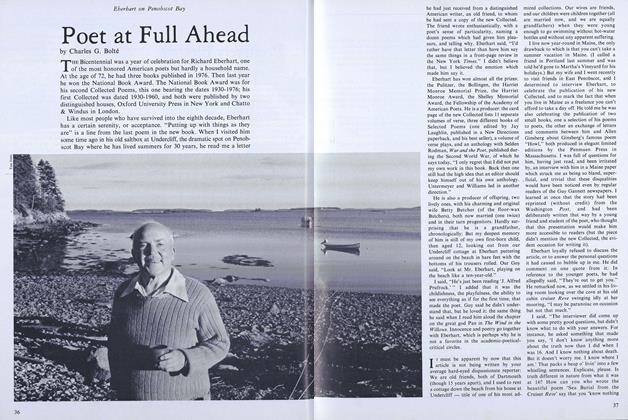

FeaturePoet at Full Ahead

September 1978 By Charles G. Bolte -

Feature

FeatureTHE RIVER and THE DAMS

September 1978 -

Article

ArticleA Journey: Five days to Big Rapids

September 1978 By Dan Nelson -

Article

ArticleDickey-Lincoln: Who wants it? Who needs it?

September 1978 By Greg Hines -

Article

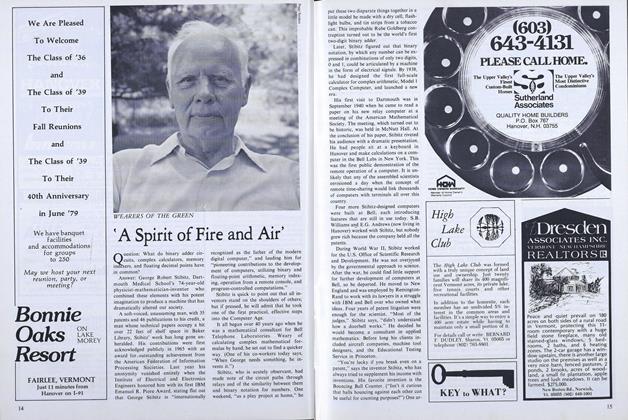

Article'A Spirit of Fire and Air'

September 1978 By NARDI REEDER CAMPION