With this number the editor brings the story of Occom toa close. Less than half the account kept so diligently bythe gifted Mohegan has appeared in the pages of the Magazine, but the editor hopes that some time the whole journalmay be printed. Its inter est to the generalreader is doubtful,but to the student of religion in the 18th Century and toDartmouth men interested in the early days of their college,this manuscript should mean much. If there should evercome from the alumni a demand for more of the Occomstory the editor will be glad to print it, but at the presenttime it seems advisable to discontinue the narrative, as ithas already run through five numbers. Some missingmaterial including a picture showing Occom preachingbefore the King may be discovered in time, here or inEngland. And it is probable that many interesting incidents of Occom's visit to England may later come to lightin England. Historians as a rule are likely to slightDartmouth in general histories, the reason being that muchof the early history of the Moore School and College wasenacted in the wilderness and forest, and this history hasnever seemed to attract Dartmouth scholars who shouldhave known of the important place of Dartmouth's antecedents and the college itself in Colonial life. Thanks toChase and Lord and more recently Foster, much originalmaterial dealing with the College has been preserved.Every alumnus should read at least Quint's Story of Dartmouth, and from that popular and readable work couldprogress to the more detailed histories. One owes it toone's College to know something about its history.

HOW SAMSON TAUGHT THE INDIANS

A ND some Indians at Shenooak sent their children /—lk to my school at Montauk. I kept one of them some time, and had a young man a half year from Mohegan, a lad from Nahantuck, who was with me almost a year, and had little or nothing for keeping them. My method in the school was: as soon as the children got together and took their proper seats, I prayed with them and then began to hear them. I generally began with those that were yet in their alphabet, and I obliged them to study their books and to help one another. When they could not make out a word they brought it to me and I usually heard them in the summer season eight times a day, four in the morning and afternoon. In the winter season six times a day. As soon as they could spell, they were obliged to spell whenever they wanted to go out. I concluded with prayer. I generally heard my evening scholars three times round, and as they go out of the school every one that can spell is obliged to spell a word and so go out leisurely, one after another. I catechised three or four times a week according to the Assembly's shorter catechism, and many times proposed questions of my own and in my own tongue.

I found difficulty with some children, who were some- what dull; most of these can soon learn to say over their letters; they distinguish the sounds by the ear, but their eyes can't distinguish the letters. The way I took to cure them was by making a small alphabet on small bits of paper and glued them on small chips of cedar after this manner: A B &c. I put these letters in order on a bench and bid a child take notice of it, and then I order the child to fetch me the letter from ye bench. If he brings the letter, it is well; if not he must go again and again until he brings ye right letter. When they can bring any letter, this way, then I just jumble them together and bid them to set them in alphabetical order, and it is a pleasure to them, and they soon learn their letters in this way.

TEACHING RELIGION

My method in our religious meetings was this: Sabbath morning we assemble together about 10 o.c. and begin with singing. We generally sung Dr. Watt's Psalms or Hymns. I distinctly read the first psalm or hymn first, and then give the meaning of it to them, after that sing, then pray, and sing again after prayer. Then proceed to read to them some suitable portion of the Scripture, and to just give the plain sense of it in familiar discourse, and apply it to them; so conclude with prayer and singing. In the afternoon and evening we proceed in the same manner.

Some time after Mr. Horton left these Indians, there was a remarkable revival of religion among them, and many were hopefully converted to the saving knowledge of God in Jesus, and it is to be assured before Mr. Horton left these Indians they had some prejudices infused in their minds by some of those exhorters from New England against Mr. Horton, and many of them had left him; by this means he was discouraged, and sewed a dissention, and was disliked by these Indians. And being acquainted with the enthusiasts in New England, I took a mild way to reclaim them. I opposed them not openly, but let them go on in their way, and whenever I had an opportunity I would read such passages of Scriptures as I thought would confound their notions, and I would come to them with all authority saying "thus saith the Lord," and by this means the Lord was pleased to bless my poor endeavors, and they were reclaimed and brought to hear almost any of the ministers.

HOW SAMSON LIVED

I am now to give an account of my circumstances and manners of living. I dwelt in a Wigwam, a small hut framed with small poles and covered with mats made of flags, and I was obliged to remove once or twice a year about 2 miles distance, by reason of the scarcity of wood, for in one neck of land they planted their corn, and in another they had their wood, and I was obliged to hire my corn carted and my hay also, and I got my ground plow'd every year which cost me about 12 shillings an acre and I kept a cow and horse, for which I paid 21 shillings every year currency, and went 18 miles to mill with a horse or ox cart, or on horse back, and some time went myself.

My family increasing fast and my visitors also I was obliged to contrive every way to support my family; I took all opportunities to get some thing to feed my family daily. I planted my own corn, potatoes and beans. I used to be outwhoeing corn some time before Sun Rise, and after my school is dismist, and by this means I was able to raise my own pork, for I was allowed to keep 5 swine. Some mornings and evenings I would be out with my hook and lines to catch fish, and in the fall of the year and in the spring, I used my gun for we lived very handy for fowl, and I was very expert with gun, and fed my family with fowl. I could more than pay for my powder-shot with feathers.

At others times I bound some books for Easthampton people, made wooden spoons and ladles, stocked guns, and worked on cedar to make pails, piggins and churns. Besides all these difficulties I met with adverse Providence. I bought a mare, had it but a little while, and she fell into the Quick-Sands and died. After a while bought another, I kept her about half year, and she was gone, and I never have heard of nor seen her from that day to this; it was supposed some rogue stole her. I got another and she died with a distemper, and last of all I bought a young mare and kept her till she had one colt, and she broke her leg and died, and presently after, the colt died also. In the whole I lost 5 Horse-kind,— all these losses helped to pull me down, and by this time I got greatly in debt, and acquainted my circumstances to some of my friends, and they represented my case to the commissioners of Boston and interceded with them for me, and they were pleased to vote 15 pounds for my help, and soon after sent a letter to my good friend at New London, acquainting him that they had superseded their vote.

SAMSON LEARNS THE WAY OF THE WORLD

All my friends were so good as to represent my needy circumstances still to them, and they were so good at last as to vote 15 pounds and sent it for which I am very thankful; and the good Mr. Buell was so kind as to write in my behalf to the gentlemen of Boston, and he told me they were much displeased with him, and heard also once and again that they blamed me for being extravagant. I can't conceive how these gentlemen would have me live. I am ready to pardon their ignorance and would wish they had exchanged circumstances with me but one month, that they may know by experience what my case really was; but I am now fully convinced that it was not ignorance.

For I believe it can be proved to the world, that these same gentlemen gave a young missionary, a single man 100 pounds a year, and fifty pounds for an interpreter, and thirty pounds for an introducer, so it cost them one hundred and eighty pounds in one single year, and they sent too where there was no need of a missionary. Now you see what difference they made between me and other missionaries; they gave me one hundred and eighty pounds for TWELVE years' service, the same that they gave for one year's service in another mission. In my service (I speak like a fool but I am constrained) I was my own interpreter, I was both a schoolmaster and minister to the Indians, yea I was their ear, eye, and hand, as well as mouth.

I leave it with the world, wicked as it is, to judge, whether I ought not to have had half as much as they gave the young man just mentioned|which would have been but fifty pounds a year. And if they ought to have given me that, I am not under obligations to them; I owe them nothing at all. What can be the reason that they used me after this manner?

I can't think of anything but this, as a young Indian boy said who was bound out to an English family and used to drive the plow for a young man, and he whipt and beat him almost every day, and the young man found fault with him, and complained of him to his master, and the poor boy was called to answer for himself before his master, and he was asked what he did that he was so complained of, and beat almost every day. He said he did not know, but he supposed it was because he could not do any better; but says he "I drive as well as I know how, and at other times he beats me because he is of a mind to beat me; but I believe he beats me for the most of the time BECAUSE I AM AN INDIAN."

I am ready to say they have used me thus, because I can't instruct the Indians as well as other missionaries; but I can assure them I have endeavored to teach them as well as I know how, but I must say "I believe it is BECAUSE I AM A POOR INDIAN."I CAN'T HELP IT. GOD MADE ME SO; I DID NOT MAKE MYSELF SO.

[The End]

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Class Notes

Class NotesCLASS OF 1923

April 1929 By Truman T. Metzel, "Charlie Chadbourne" -

Article

ArticleThe Vicissitudes of South Hall

April 1929 By Edwin J. Bartlett -

Lettter from the Editor

Lettter from the EditorEditorial Comment

April 1929 -

Article

ArticleFrench Life at Dartmouth

April 1929 By Howard F. Dunham -

Class Notes

Class NotesCLASS OF 1899

April 1929 By Louis P. Benezet -

Article

Article"The Dartmouth," An Explanation

April 1929 By W. L. Scott, Editor

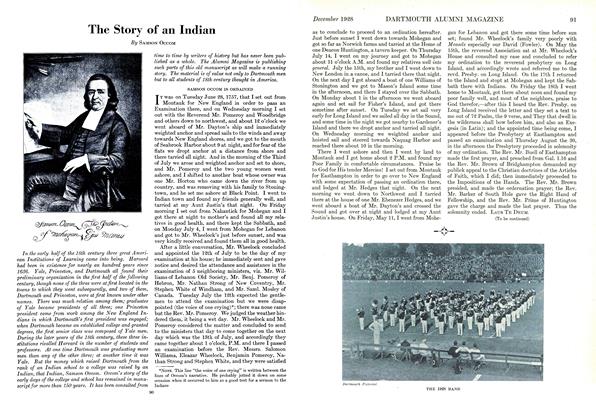

Samson Occom

Article

-

Article

ArticleAlumni Dinner Speakers

January 1951 -

Article

ArticleFACULTY

Sept/Oct 2008 -

Article

ArticleTHE FACULTY

MAY 1965 By GEORGE O'CONNELL -

Article

ArticleHanover Browsing

August 1944 By HERBERT F. WEST '22 -

Article

ArticleDARTMOUTH ALUMNI OUTING CLUB

February 1935 By John F. Hardham '36 -

Article

ArticleArts Catalyst

MARCH 1973 By MARY ROSS