INSTITUTIONS of higher learning, particularly liberal arts colleges, exist primarily for one fundamental reason: to promote the values of civilization, namely, tolerance, social harmony, thoughtfulness, and intellectual endeavor. Contrary to popular belief, the atmosphere for such activity is fragile and subject to disruptive external and internal forces. Every college in the country feels and responds to the demands of the larger society. Every college is also subject to internal stresses, any one of which can dissipate that delicate, indeed precious, atmosphere in which the values of civilization are professed, discovered, and enhanced.

When a large group within a college fosters values in conflict with those of the institution, a division of purpose results, and the institution must respond to heal the division and preserve the atmosphere and values so necessary to the promotion of its purpose. Otherwise, these opposing sets of values create a divided community. A large number of the faculty of Dartmouth believe that just such a division exists now within the College.

There appear to be two opposed standards, those of the institution and those of the fraternities. In the past decade the Trustees . have ordered that women and an increased number of minorities be accepted as students, yet many fraternities perpetuate sexual and racial stereotypes that humiliate and degrade women, blacks, and American Indians.

The College, for more than two centuries, has honored intellectual excellence, yet many fraternities denigrate fine, industrious students by referring to them as ''geeks" or "tools." So powerful is this contemptuous attitude toward learning that many dedicated students feel they must disguise their devotion to study or to other activities that do not fit the fraternity conception of a "Dartmouth man."

The College, by its very nature, values creation and not destruction, health not illness, social harmony and not anarchy. Yet many fraternities in the past few years have become notorious for their destruction of property, the slovenly maintenance of their houses and grounds, and their financial irresponsibility. They encourage excessive drinking to the point that students have become seriously ill, or have been deflected from the activities for which they presumably enrolled at Dartmouth -their studies, athletics, and social pleasures. Community events are too frequently disrupted by loutish exhibitions emanating from fraternity "blocks" - obscene cheers, public urination, vomiting, and other disgusting and depressing acts.

This is not to say that Dartmouth has no civilized students. The offenders represent a minority, but a sizable and vocal minority, one that, for better or worse, sets the general tone of behavior on the campus and that carries an image of Dartmouth to the public.

Every thoughtful member of the Dartmouth community even men in fraternities - admits these problems. The real question then becomes, what can we do to solve them? What can we do to restore the atmosphere required for the promotion of civilization? These were precisely the questions pondered by the faculty on November '6. The answer given by that body was decisive and unambiguous: abolish the fraternities. To those out- side the community, such a decision no doubt seems harsh, peremptory, and extreme. Why not reform the fraternities, "crack down" on their excesses, especially since there have been faint signs of reform during the summer and fall? It was expected that the faculty would defeat the motion to abolish and propose steps for reform. However, several persuasive arguments for abolition came forth.

First, reform has consistently failed. Since 1926, periodic attempts to integrate fraternity values with the purposes of the College have met with little success. Second, at a residential college, coeducation means more than men and women in the classroom. It also means social equality; sororities are separate and therefore unequal. Third, recent attempts to impose reform have met strenuous and irrational fraternity resistance, overcome only by threats of abolition. The combined force of these and other arguments persuaded the faculty to recommend to the Trustees the abolition of fraternities and sororities at Dartmouth.

Where do we go from here? No one is second-guessing the Trustees, who will decide the matter. If the Trustees reject or modify the faculty recommendation, at least the message from the faculty and many students to the fraternities is unmistakable: change your ways, conform with the purposes of the College.

Should the Trustees accept the faculty recommendation, should they be persuaded that, however painful, abolition of fraternities is a necessary step in the direction of full and equal integration of minorities and women, and is a necessary step in maintaining Dartmouth's function as a promoter of civilization, then the prospect before us is one of challenging possibility.

Dartmouth would be in a position to create new and healthy patterns of social life, standards of intellectual excellence, and op-portunities for personal growth. We would continue to attract fine students, skillful athletes, and talented artists, and these exceptional young people would enter a Dartmouth of variety and, one hopes, harmonious diversity. The industrious now-intellectual would, as always, be welcome, but he would not (one again merely hopes) become the anti-intellectual oaf, the fabled "Dartmouth Animal," now so evident in the community.

Practical questions concerning the fate of the houses themselves, the housing of those who live in the fraternities(about 400 students altogether), and provisions for alternative social groupings can be answered in a number of ways. The houses might become small dormitories, well maintained and efficiently managed, attracting students who share an interest in, say, soccer, music, French, mountaineering, or chemistry. We are limited only by our imaginations and our resources. The future is all before us, as it has been for the College since 1769. Our goal now and always is to unify that small yet valuable community we call Dartmouth, to share equally in a common purpose of immense significance - the promotion of civilized values.

Finally, it is fervently hoped that the men and women who love the College, yet who are distant from it in space or time, will understand that those of us who live and work within the institution are trying to solve a long-standing problem, and that our proposed solutions are humane, creative, rational, and necessary. No doubt there will be strong responses to whatever solution is adopted regarding the fraternity problem. Let those reactions be in the form of helpful commentary rather than furious rejections and harsh condemnations. Recollections of Dartmouth Past should indeed be cherished, but not at the expense of Dartmouth Present and Future, the ever-changing College in which we all take such genuine pride.

Professor Epperson drafted the motion, approved by faculty vote,to abolish fraternities at Dartmouth. See also page 16.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

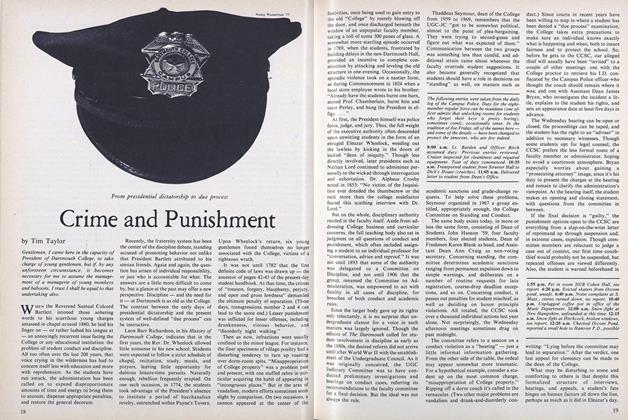

FeatureCrime and Punishment

December 1978 By Tim Taylor -

Feature

Feature'Raucous behavior of a different sort'

December 1978 By Mary Ross -

Feature

FeatureParadise Lost or Paradise Regained?

December 1978 -

Feature

FeatureGOOD NEWS

December 1978 -

Article

Article'Most Improved Professor'

December 1978 By NARDI REEDER CAMPION -

Article

ArticleStraight Shooter

December 1978 By D.M.N.