Following closely after the weather and vacation as a subject for breakfast-table and street-corner talk was the announcement of the Senior Fellowships to be awarded beginning next year. The interest was not confined to the juniors as being most immediately interested, but was spread rather completely through the classes. Undergraduates as a rule enjoy Dartmouth's reputation as a liberal and progressive institution, and are pleased when the College makes a notable advance of this sort. The Dartmouth's editorial on the Fellowships said, in part:

"The establishment of five Senior Fellowships, announced in today's paper, marks a significant and progressive step forward in the carrying out of the liberal theory of eduhour cation at Dartmouth. By virtue of its novelty, the establishment of these Fellowships is probably the most outstanding of all the steps yet taken towards the ultimate realization of that theory.

"Strictly speaking, it is not an experiment. It is the capstone of the new trend in educational policy which was inaugurated some three or four years ago—the logical culmination of the same policy which has been responsible for the adoption of the new curriculum, the honors groups, and the comprehensive examinations.

"In the past the exceptional student has received less attention than he deserved. Education has been primarily for the masses. The academic machinery has consequently been tuned to the demands and capabilities of the average student. It has been keyed to mediocrity. There has been insufficient realization of the fact that wide variations in mental capacity and ability exist between different individuals. So while the standards of education have been high enough to weed out the few at the bottom who, are obviously incapable of deriving any advantage from the educational process, hardly any attention has been paid to those at the top who often have felt themselves hampered, instead of assisted, by the restrictions laid down for the benefit of the majority.

"The complicated machinery of tests, entrance requirements, degree requirements, attendance requirements, exams, etc., has been necessary in order that the college may make itself effective with this middle group. That these standardized devices have often proved a handicap to the upper group has caused such epithets as 'steam-roller methods,' 'mass production,' and 'spoonfeeding' to be frequently thrown at the American educational system. The root of the trouble has been the failure of the college to give the exceptional student the individual treatment which he required. . . .

"By serving as an incentive to the three lower classes, and as an illustration to the whole community that 'the acquisition of learning is made possible largely by individual search and in minor degree by institutional coercion,' these Fellowships should be instrumental in raising the academic tone of the college. It is to be hoped, however, that their advantages will not always be limited to five men. Perhaps the majority will some day be qualified to receive those privileges which can at present be extended only to a small minority."

There seems to be a growing appreciation among the undergraduates of the real aims of the college, and even those who have no very clear idea of what they mean by a "liberal education" will be found heartily endorsing it. To most it seems to mean freedom from compulsion and complete liberty to follow one's own inclinations in study. There is a constantly recurrent wail about quizzes, exams, and the cut system, and anything promising more freedom is hailed with rejoicing.

The editor of The Dartmouth followed up his editorial on the Fellowships with the following one entitled "Freedom for the Hoi Poloi":

"Senior privileges at Dartmouth are noticeable by their absence. By senior privileges we mean privileges extending to every man in the senior class. The ordinary senior is bound by practically the same set of academic restrictions as the ordinary sophomore. He is governed by exactly the same rules of class attendance. Both have the privilege of "unlimited" cuts—unlimited in name only—if their marks are 3.2 or over. Both are subjected to the same kind of quizzes, hour exams, semester examinations. It is not likely that the comprehensives, by themselves, are regarded as any great 'privilege.' The only factor that can be called a privilege is the greater latitude allowed the senior in the choice of his studies.

"The honors work has brought a partial release from the regular requirements of classroom attendance. Yet the honors groups comprise a total of only 150 men—of whom almost half are juniors. Consequently there are a good many juniors with privileges not enjoyed by the majority of seniors. While the exceptional juniors and seniors have been given greatly increased opportunities for study and development, the status of the average senior has remained the same. The five Senior Fellowships will make more apparent the discrepancy existing between these two groups.

"We are not taking an opposite stand from our editorial of Thursday and recommending that the exceptional and the average scholar be given the same treatment. Wide differences in the methods of handling the two groups should always exist, commensurate with their differences in capacity and ability. Yet these differences should not become too great. The honors work and the Fellowships, the two most recent innovations, directly affect only the top men in each class. There should be a corresponding change in the treatment accorded the middle and lower groups.

"We wish to propose two changes: "First, the honors system should be extended to include more men. The idea would be to gradually extend, the tutorial method of education to all majors, with a constantly decreasing emphasis on classroom recitations. We realize that any such development must be slow on account of the increased financial outlay incurred by the need for a larger faculty; yet we hope that the present tendencies towards increasing the size of honors groups will continue.

"Secondly, it seems patent to us that with such a change there should come release for the seniors from compulsory class attendance. Suggestions of this kind coming from undergraduates are usually met with the criticism that their only aim is to make life easier. Yet it is certainly one of the aims of the college to develop initiative and resourcefulness. What chance has initiative to develop when entire reliance is placed on grammar-school methods of compulsion?

"The Senior Fellowships mark the goal in the development of the theory of selfeducation. Obviously it would be impractical, unwise, and financially impossible to extend these Fellowships to a much larger group than that designated in the report of the Trustees. It now remains for the College to give the remaining 99 per cent of the class the means and the opportunities to come a step nearer this goal."

The campus seems to be straightforward and sincere in its belief that with complete freedom for its own initiative and resourcefulness it could get a more valuable kind of education. We believe, however, that, with the athletic circus and the activity-mart as important as they are, the scholarly ideal has rather a meagre show in open competition, and that the College is wise in developing its program somewhat gradually.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Article

ArticleA Survey of Undergraduate Activities

May 1929 By Carl B. Spaeth -

Class Notes

Class NotesClass of 1898

May 1929 By H. Phillip Patey -

Lettter from the Editor

Lettter from the EditorFor opinions which appear in these columns the Editors alone are responsible

May 1929 -

Class Notes

Class NotesClass of 1923

May 1929 By Truman T. Metzel -

Article

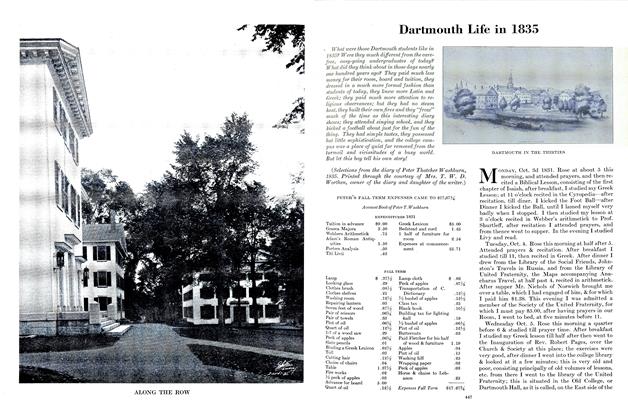

ArticleDartmouth Life in 1835

May 1929 -

Class Notes

Class NotesClass of 1910

May 1929 By Arthur P. Allen

Albert I. Dickerson

-

Article

ArticleThe Musical Clubs Trip

May 1929 By Albert I. Dickerson -

Article

ArticleHURRAY FOR FOOTBALL

January, 1930 By Albert I. Dickerson -

Article

ArticleNOOKS IN THE NEW DARTMOUTH

FEBRUARY 1930 By Albert I. Dickerson -

Class Notes

Class NotesClass of 1930

December 1932 By Albert I. Dickerson -

Class Notes

Class NotesClass of 1930

October 1937 By Albert I. Dickerson -

Class Notes

Class Notes1930*

March 1939 By ALBERT I. DICKERSON