In all fields of human endeavor, success waits upon ventures, whole-heartedly undertaken. In military affairs, Napoleon affirms, "Death is nothing, but to live defeated and ingloriously is to die every day." In the tranquil paths of literature, Keats declares: "In Endymion I leaped headlong into the sea and thereby have become better acquainted with the soundings, the quicksands and the rocks than if I had stayed upon the green shore and piped a silly pipe and had taken tea and comfortable advice. I was never afraid of failure, for I would sooner fail than not be among the greatest." No fame without risk. In an even higher realm, Milton is equally emphatic: "I cannot praise a fugitive and cloistered virtue, unexercised and unbreathed, that never sallies out and seeks her adversary but slinks out of the race. That which purifies us is trial and trial is by what is contrary to us." No purity without risk.

Seeing then that society, literature, science, virtue, depend upon risks nobly taken, why is it that "Safetyfirst" still assails our eyes from innumerable posters along the public ways? It is, alas, because men who ought to be taking noble risks insist on taking ignoble ones. Whoever will save his life shall lose it, says Jesus. That is unequivocal and unqualified. The policy of withdrawal from conflict and danger is fatal. But it does not therefore follow that whosoever is willing to lose his life shall save it. You must lose it in a high enterprise to be sure of saving it. So Jesus inserts a qualification in this half of his well-known paradox. "Whosoever loseth his life for my sake and the gospels shall save it." It is only a man's ideal or his duty that can justify a great risk. To get into bed with a boy who has measles, as Mark Twain did, to sail in solitary daring across the Atlantic in a 22-foot catboat, to fly to the North Pole because no one has been there before, to overtake and pass a motor car on a curve you cannot see around—this is the kind of risk that makes safety-first posters popular and necessary. I know of no better guide in this delicate matter than Pasteur. He refused to eat grapes without dipping them in his tumbler, in order to avoid the germs to which no duty called. But when cholera broke out in the city, he moved his desk to a room immediately above the cholera ward, that he might better investigate the germs whose dread secrets he had set himself to conquer. The philosophy of life that I am urging upon you by means of this parable and of human experience is not, Take any risk but Take the nobler risk. Some risk you must take. Even the adoption of the policy of safety-first is a risk. Seeing that life demands some risk, demand of yourself that you take the nobler one. Do not simply contemplate a risk; take it.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Class Notes

Class NotesCLASS OF 1879

August 1929 By Henry Melville -

Article

ArticleAlumni Council Meetings

August 1929 -

Article

ArticleThe One Hundred Fifty-Eighth Commencement

August 1929 By Eugene F. Clark -

Class Notes

Class NotesCLASS OF 1899

August 1929 By Warren C. Kendall -

Class Notes

Class NotesCLASS OF 1903

August 1929 By John Crowell -

Class Notes

Class NotesCLASS OF 1918

August 1929 By Frederick W. Cassebeer

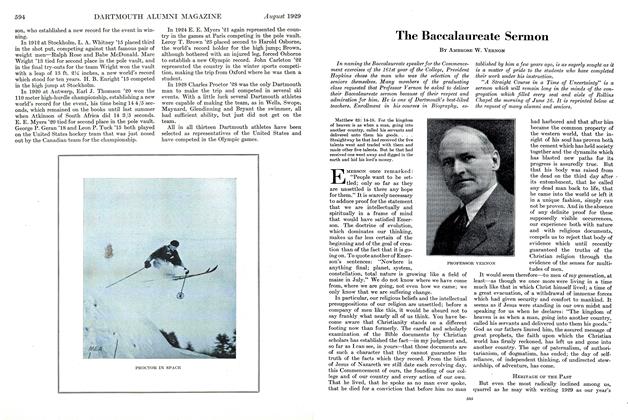

Ambrose W. Vernon

-

Article

ArticleThe Baccalaureate Sermon

AUGUST 1929 By Ambrose W. Vernon -

Article

ArticleHeritage of the Past

AUGUST 1929 By Ambrose W. Vernon -

Article

ArticleTwo Courses Open

AUGUST 1929 By Ambrose W. Vernon -

Article

ArticleResults of Risks

AUGUST 1929 By Ambrose W. Vernon -

Article

ArticleTake the Nobler Risk

AUGUST 1929 By Ambrose W. Vernon -

Article

ArticleThe Supreme Risk

AUGUST 1929 By Ambrose W. Vernon

Article

-

Article

ArticleHARVARD-DARTMOUTH FOOTBALL ENDED

-

Article

ArticleR. O. T. C. TRAINING CAMPS

December 1917 -

Article

ArticleART DEPARTMENT ACQUIRES ALBERTINA COLLECTION

April, 1925 -

Article

Article"Why, inadequate?

November 1938 By Ralph N. Hill '39 -

Article

ArticleAcademic Freedom

November 1940 By The Editor -

Article

ArticleEducational Policy

May 1935 By The Editors