A great risk almost invariably fascinates us. Why should it not? Life itself is the result of a risk. We came into the world at the risk of our mothers' lives and if they had not been willing to take the risk, we should not be here at all. We are made to love a risk, if we love human life; for human life is what happens at cost of a risk. That is fundamental; we cannot get away from it.

As Americans, also, we are the products of great risk. Ever since the time of the Greeks, people could be found who believed the world was round, but nobody would take the risk of acting on that belief. Columbus risked it. Had he wanted to save his life, he would have stayed in the court at Grenada or among the looms of Genoa; he wanted, however, to do something with it, so he drummed up a crew, got on board the little caravel, pointed its pigmy bow toward the west and America was born.

And the United States of America is the result of another risk. It was not enough to discover a new continent; it was not enough to plan a new England; this continent had to be owned by those who lived upon it. But to accomplish it a peculiarly unpromising risk had to be taken. It was so fearful that it drove Washington into rhetoric. "The once happy and peaceful plains of America," he said, "are either to be drenched with blood or inhabited by slaves. Can a virtuous man hestitate in his choice?" In Washington's eyes, safetyfirst meant slavery; to him but one course was open; he took the nobler risk and out of it our nation rose to life.

Nor should we pass over such an obvious confirmation of this philosophy of life as the figure of the founder of Dartmouth College. On surveying, the sweep of our country and comparing it with the small patch of land that was fenced about for Moor's Charity School in Lebanon, Connecticut, he determined to risk what he had for the sake of that into which it might grow. One of the things that was uppermost in his mind was space. So he refused Albany's inducement of 2500 pounds, sterling, and "the generous offers made by particular towns and parishes in the colony of Connecticut. For, the country being so filled up with inhabitants, it was not practicable to get so large a tract of lands as was thought to be most useful for it." "So, for many weighty reasons" the gentlemen of the trust in England "gave the preference to the western part of the province of New Hampshire on Connecticut river and determined that to be the place for it." But the risk, which seems so great to us, only occasionally appalled him. Hear, again, his own words: "A little more than three years ago, there was nothing to be seen here but a horrid wilderness; now there are eleven comfortable dwelling-houses and some of them reputable ones. "When I think of the great weight of present expense, I have sometimes found faintness of heart, but when I consider I have not been seeking myself in one step I have taken, nor have I taken one step without deliber ation and asking counsel therein, and not only so but I have always made it my practice not to suffer my expenses to exceed what my own private interest will pay in case I should be brought to that necessity to do my creditors justice," then a dash like one of Saint Paul's and the sentence left hanging in the air, while its author lands on the great assertion: "But the consideration, which above all others has been my sovereign support, is that it is the cause of God and in Him do I hope to perfect His own plan for His own glory." That plan is still being perfected; it is not Wheelock's plan, but the risk which he took and the wholeheartedness with which he invested all he had in the enterprise are on their way to their justification. Here we sit reverently to day, the product of noble risks of unselfish men; without self-stultification, we cannot turn our backs upon their policy of daring.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Class Notes

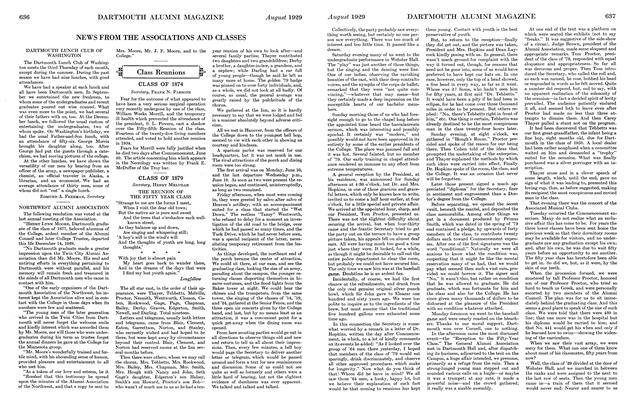

Class NotesCLASS OF 1879

August 1929 By Henry Melville -

Article

ArticleAlumni Council Meetings

August 1929 -

Article

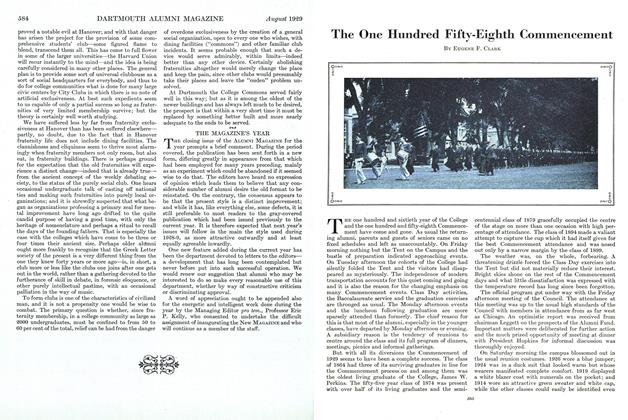

ArticleThe One Hundred Fifty-Eighth Commencement

August 1929 By Eugene F. Clark -

Class Notes

Class NotesCLASS OF 1899

August 1929 By Warren C. Kendall -

Class Notes

Class NotesCLASS OF 1903

August 1929 By John Crowell -

Class Notes

Class NotesCLASS OF 1918

August 1929 By Frederick W. Cassebeer

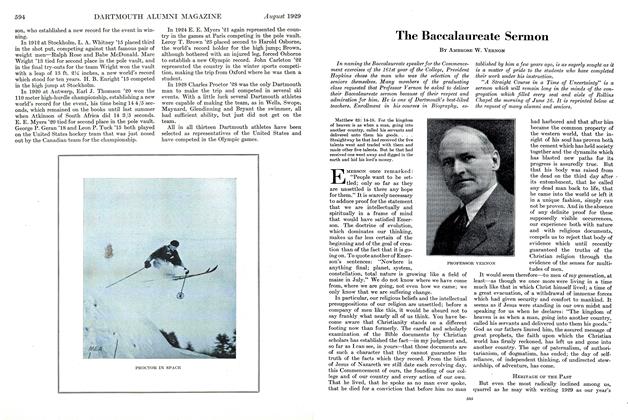

Ambrose W. Vernon

-

Article

ArticleThe Baccalaureate Sermon

AUGUST 1929 By Ambrose W. Vernon -

Article

ArticleHeritage of the Past

AUGUST 1929 By Ambrose W. Vernon -

Article

ArticleTwo Courses Open

AUGUST 1929 By Ambrose W. Vernon -

Article

ArticleDiscrimination in Risks

AUGUST 1929 By Ambrose W. Vernon -

Article

ArticleTake the Nobler Risk

AUGUST 1929 By Ambrose W. Vernon -

Article

ArticleThe Supreme Risk

AUGUST 1929 By Ambrose W. Vernon

Article

-

Article

ArticleOPPORTUNITIES FOR FELLOWSHIPS FOR GRADUATE STUDY

February, 1923 -

Article

ArticleBequests Made to College By '72 and 'B9 Widows

February 1953 -

Article

ArticleMasthead

February 1993 -

Article

ArticleGive a Rouse

Nov/Dec 2003 -

Article

ArticleThayer School

December 1951 By Davis, Fred R. '95 -

Article

ArticleGRADUS AD PARNASSUM

May 1940 By The Editor