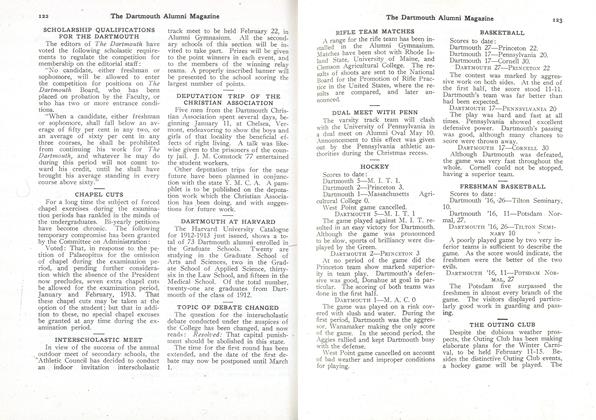

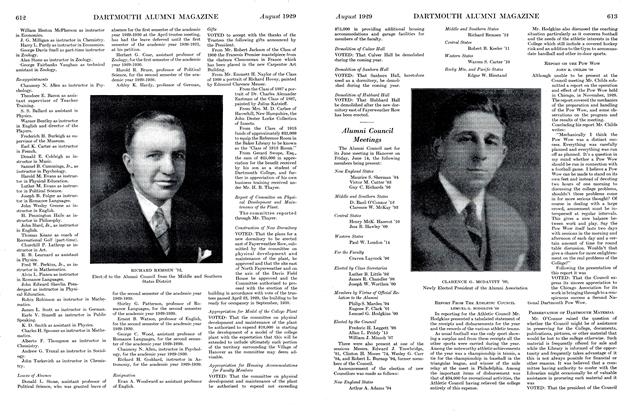

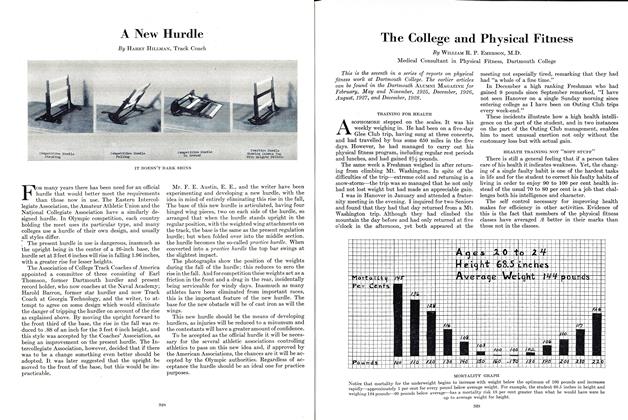

Coach of the Dartmouth Track Team

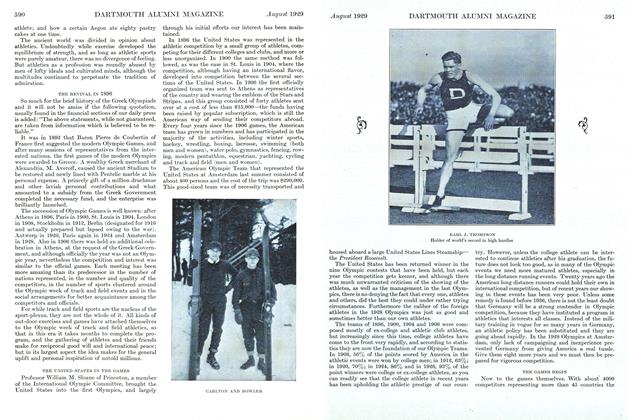

Here you have glimpses of the Olympics by a man whohas competed in, trained, observed, and coached OlympicTeams. He has touched one or two of the high spots of thegames, and has mentioned the Dartmouth men who havetaken part. Dartmouth has been represented at most of theOlympic games though curiously enough in the last Olympics none of the Dartmouth track men were chosen, although two or three of them were record men; namely, Wellsthe hurdler and Maynard the high jumper; likewise Bryantin the swimming events. There seems to be a lack of photographs of the earlier contenders as an unfortunate fire inHanover destroyed many of the old time pictures, butphotos of Shaw, Wright, and Sherman are earnestly desired.

The Greek Olympiads were begun by the people of Pisa; the Eleans organized them; the Spartans confirmed and regulated them; and after 572 B.C. they remained well on into Christian times (A.D. 293). They were the expression of what Greece stood for in the pagan world: moderation, proportion, discipline, the oneness of body and soul, the interaction of these qualities as the best known service to the Olympian Zeus. It is significant that the list of Olympic victors begins with Coroebus, an Elean, in 776 B.C. and closes a thousand years later with the name of Varastad, an Armenian. First the germ, then Hellenic product, finally the Hellenistic influence on the outskirts of the known world.

The first exercises were of the Spartan type, to create endurance and strength. To these were added early the four-horse chariot race, to enlist the interest and secure the presence of the opulent and fashionable. Steadily the list of Stadium exercises grew: first the sprint; then the middle and long distance foot races; wrestling and boxing were joined in the pancration; the pentathlon was added to these. And as time passed, the athletes were, up to a certain point, of higher and higher social quality, while naturally all the distinguished men of antiquity came as visitors.

An athlete was one who trained for participation in the public games. Later it was designated for those who actually contested. So far the contestants, even the victors, had devoted but a portion of their time to training and were what we now term amateurs. Frequently they belonged to the first families of their town and were themselves men who held high office in the community.

Honors which seem to us preposterous were paid to a conqueror, whatever his walk in life. The Olympic crown itself was a simple wreath of wild olive culled with religious ceremonial. But very different was the visitor's reward on his return home. Mounted in a chariot drawn by four white horses, clad in a mantle of Tyrian purple, surrounded by relatives and friends, accompanied by a vast concourse of fellow citizens, the victorious athlete entered the city in a blaze of glory. Later, statues and columns were erected to the honor of the victor. In some instances there was even given to him the right of a "Sitesis," free subsistence for life. The athletes' money rewards were, for three centuries, immense. Of course there were likewise a number of lawless, unmanly athletes, and some cowards, who shirked certain defeat. For all such the penalties were severe and were administered without fear or favor; however, whether amateurs or professionals, the famous athletes of Greece and even of Rome maintained a high moral standard of living.

According to Galen the athletes' life consisted of eating, drinking, and rolling in dust and mud. They rose late from sleep and the entire time from breakfast to a late dinner (lasting frequently until midnight) was devoted to severe exercise. They were absolutely forbidden to discuss at meals anything but the lightest topics, but they must eat very much and very slowly at dinner, principally of meat, and for the most part of pork. Incredible tales are told: how Milo of Crotonoa ate a whole ox at one sitting; how Galen considered six and a half pounds of meat a very small portion for an athlete; and how a certain Aegon ate eighty pastry cakes at one time.

The ancient world was divided in opinion about athletics. Undoubtedly while exercise developed the equilibrium of strength, and so long as athletic sports were purely amateur, there was no divergence of feeling. But athletics as a profession was roundly abused by men of lofty ideals and cultivated minds, although the multitudes continued to perpetuate the tradition of admiration.

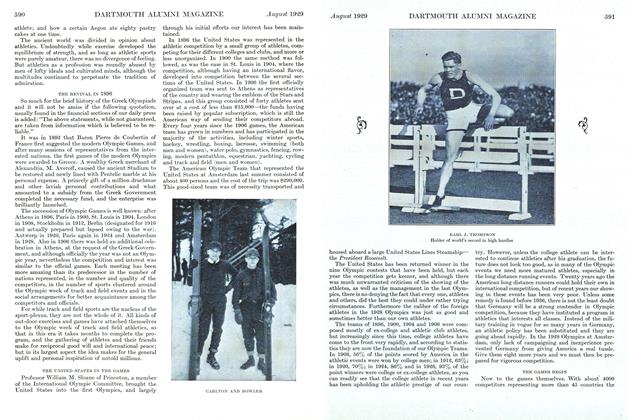

HARRY HILLMAN Trainer of Olympic Team, and Dartmouth Team, hurdler and coach

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Class Notes

Class NotesCLASS OF 1879

August 1929 By Henry Melville -

Article

ArticleAlumni Council Meetings

August 1929 -

Article

ArticleThe One Hundred Fifty-Eighth Commencement

August 1929 By Eugene F. Clark -

Class Notes

Class NotesCLASS OF 1899

August 1929 By Warren C. Kendall -

Class Notes

Class NotesCLASS OF 1903

August 1929 By John Crowell -

Class Notes

Class NotesCLASS OF 1918

August 1929 By Frederick W. Cassebeer

Harry Hillman

-

Sports

SportsTHE REVIVAL IN 1896

AUGUST 1929 By Harry Hillman -

Sports

SportsTHE UNITED STATES IN THE GAMES

AUGUST 1929 By Harry Hillman -

Sports

SportsTHE GAMES BEGIN

AUGUST 1929 By Harry Hillman -

Sports

SportsA THRILLING MARATHON

AUGUST 1929 By Harry Hillman -

Article

ArticleA New Hurdle

MARCH 1931 By Harry Hillman -

Sports

SportsVARSITY TRACK

January 1942 By Harry Hillman