For opinions which appear in these columns the Editors alone are responsible

THE ANNUAL PANEGYRIC

ONE of the pleasantest of the annual duties of the editors of this MAGAZINE at this season is to hymn the excellences of the Outing Club—an organization born of Hanover's boreal situation which probably figures near the very top of Dartmouth assets, if one may repose confidence in the sincerity of those who ascribe reasons for selecting our College from the hundreds available throughout the country. Dartmouth's out-door life is certainly mentioned very often in such lists; and the Outing Club is far excellence the out-door organization, which reaches its full flower of activity in the dead of winter.

To convert what of old was Hanover's greatest drawback into what it is now—Hanover's most distinctive attraction—has taken a bit of doing, but it has been done. One recalls the long cold winters of a generation ago and more, during which the annual hibernation began with the close of November and ended only with the drying up of the mud in March or April. Life in a country town, where there was neither a water supply nor any pretense of central heat, lacked attractions for the many and winter became a season in which rooms were hermetically sealed to confine the warmth originating from an air-tight stove. The idea of hastening forth with glad shouts to greet Old Man Winter had not taken hold of the undergraduate imagination. Pilgrimages on snowshoes or skis to remote mountain peaks were not so much as dreamed of. There was no conception of a Winter Carnival to serve as the reason for summoning youth and beauty to Hanover, for Hanover in winter was regarded as a place to avoid if one could. That's all changed now, and the once dreaded period of snow and ice has become a chief festal season.

One may not justly say it has outlawed completely the sentiment which prompts one to give a rouse by the fire—pass the pipes, pass the bowl. There are still charms such as Horace sang when he surveyed distant Soracte and attuned his lyre to sing the comfort of the blazing logs. But the sturdy sons of Dartmouth are no longer climate-cowards who dread the advent of lusty winter. Their disposition is to make the most of it, and they do. This year the facilities for winter sport surpass any hitherto enjoyed, both in point of material equipment and in point of programs for its utilization, whether close to Hanover or far afield among the snowclad hills. The opinion is here renewed that it is one of the best things about the modern Dartmouth—one of the things best calculated to war with cynicism and laziness.

MORE CARNEGIE WISDOM

THAT prolific source of voluminous bulletins, the Carnegie Foundation for the Advancement of Teaching, has lately promulgated Bulletin 24 on "The Literature of American School and College Athletics" as an appropriate supplement to the one issued last year on professionalism in athletic circles. The present document, a volume of 305 pages, merely summarizes and digests the material unearthed by an examination of more than a thousand books and periodical articles concerning school and college athletics—practically all that ever has been written in this country of any importance on the subject. The chief director of this work is Professor W. Carson Ryan of Swarthmore.

The report is summarized under ten headings, not all of which can be touched on here. Speaking of the points generally, it is recognized that athletics, once opposed and then grudgingly tolerated, now figure as an accepted part of the scheme of education—the opposition, such as there is, confining itself only to combat over-emphasis and commercializing. It is urged that athletics be administered educationally by the institutions themselves —but Dr. Pritchett of the Foundation, who appends an introduction, rather despairingly remarks that "some of the institutions that have most completely adopted the doctrine of faculty control have been found to be doing most to impair the status of the amateur," so that "on the one hand we meet with high claims regarding the purifying values of faculty control, and are confronted, on the other hand, with results of its application that are helpful neither to sport nor to education."

Another paragraph in the summary asserts—and this seems rather refreshing—that "the claim that athletics seriously interfere with scholarship remains unproved." It is also admitted that as to health, college athletes are found to have a better expectancy than the general population, but no better than the college (non-athletic) population—and not so good an expectancy as that of college men of high scholastic standing. So, apparently, wisdom doth indeed have in her right hand length of days! Then follows a section devoted to hymning that favorite ideal of the theorist, "intramural" contests designed to make every student to some measure an athlete and constituting a part of the curricular scheme—perhaps the very best way that could be devised of robbing athletics of nine-tenths of their allurement.

Coaches and athletic directors, we read, "are regarded as highly important teachers of youth" which is true, and also justifiable as a belief; but everything, of course, depends on the coach—his character, his ideals, his ability to impart them. And so forth and so on.

One must remember that this is a summary of the ideas of the multitude who have written books and articles about college and school athletics, rather than a statement of the opinions of the Carnegie commentators on the same. In fine, this is not a statement of what the Carnegie Foundation thinks, but rather of what writers about the subject have thought. This material, collated, winnowed and sifted, leads to the conclusions above set forth. No doubt those who wrote most of the histories of athletics and the articles about athletics have written con amore and with complete sympathy with the institution itself.

THE HISTORY OF BUSINESS

BUSINESS is a very elastic term, as we all know, coving a field which has never had a particularly descriptive name. What to the Latins was negotium, or lack-of-leisure, is to moderns a concentrated form of "busy-ness"; and the things one may be busy about are so numerous that no doubt a comprehensive description is impossible. The young man who, on entering college, announces that at the close of his course he proposes to "go into business" says everything and nothing.

Yet business is coming into its own as a domain with which the intellectual institutions may have to do without shame. One has but to recall the magnificent department for the study of business, finance and administration on the "right bank" of the Charles at Harvard, or the swiftly growing Tuck school at Hanover, to realize that business is no longer treated as a thing apart from the educational activities of colleges and universities which of old confined themselves to the cultural alone. Business is studied now with scientific zeal, much as law, medicine, dentistry, engineering and other useful activities are studied.

To this is now added the discovery that the history of business is not only interesting but is capable of being turned into a subject of detailed study with the promise of benefit to mankind. Hence the formation of the Business Historical Society, with some 300 business men for members, who are willing to pay an initiation of $25 and annual dues of $25 more, the function of which is to assemble collections of data and other materials which set forth the practices and records of business throughout the ages. An amazing amount of valuable material has already been assembled and housed in the George F. Baker Library at the Harvard Business School—apparently as a convenient central museum, to give it that name, for the members of the association, although the association itself is not a Harvard activity. The field covered is naturally broad, including ancient records of the manifold business transactions of the powerful Medici family, as well as historical matter bearing on more modern industrial developments, such as cotton and woolen textile manufacture, shipping, mining, iron-working and railroading.

It is believed that this endeavor to ennoble the gainful arts in which mankind practice themselves into a subject of scientific analysis and study merits the most serious attention of educated men. It is no longer possible to dissociate business from professional activity, from the educational point of view. As an organized force, no doubt business as we of today understand it is rather a modern institution; but time is fleeting and there is already accumulating a history of business activities which it is well to treat with becoming seriousness in the colleges everywhere. The study of the past is valuable in any line, and the wonder is only that we have been so dilatory in recognizing how useful a study of business history could be. The active assistance and cooperation of Dartmouth men should certainly be counted on in this matter—more especially as the popularity and usefulness of the Tuck School indicate the extent to which the subject is already appreciated.

PUTTING IT UP TO COLLEGES

NOT long ago there appeared in the Atlantic Monthly an article entitled, "Putting It Up to the Colleges," which had to do with a case—possibly actual—in which a wealthy father with advanced educational ideas for his son approached the harrassed president of a college with a novel proposition. His boy was not to be subjected to the standardized routine leading to an A.8., but was to have a wholly separate course fitted to his peculiar aims and abilities, for which the father stood willing to pay $lO,OOO a year if necessary. Whether to accept that offer or reject it was the problem put up to the president—and the decision seemed to be left up in the air at the close.

Now with the multitudes that in recent years have clamored for admission to the colleges of the United States there has not unnaturally increased a tendency, which was fairly well marked before, toward standardized education. One isn't as free to deal on an individual basis with thousands of students as one could possibly do when students were numbered by scores. As a result there has been a diminished chance to devote special attention to the production of a small class of exceptional scholars, and it seems very doubtful that it can be done in the rare instance in which a rich father stands willing to pay $10,000 a year for extra-special tutoring. An effort to escape from the worse evils of enforced standardization has been begun at Dartmouth in the so-called "honors" courses, amplified in the novel experiment of choosing five or six outstanding men in senior year to become "guests of the college," who are free to pursue education without faculty oversight save such as they see fit to seek, without dues and without duties. But for the great mass of students, here and elsewhere, standardized requirements must inevitably remain the rule while conditions are what they now are—and it is somewhat to be doubted that this is as bad a thing as critics are wont to assert. At least it isn't chaos; and a certain amount of standardization appears to be heaven's first law.

After all, does it naturally follow that because 2000 young men in a given college are pursuing a common course of study they will all turn out in the end as much alike as 2000 Ford cars built under a scheme of mass production? And if they did, is it not true that the Ford cars are distinctly useful articles, despite their similarity? One doubts that the requirement of a fixed curriculum really does produce a species of what one may call "Ford humanity" although it may retard somewhat the natural self-expression of an individual character. We are taught penmanship, as a rule, by fixed systems—but very few of us write just alike in the end.

Everything in this world has some sort of defect as the attendant of its virtues—a sort of price one has to pay for the latter, no doubt. It is possible that standardized education differs in no respect from other human devices in this direction. It does slow up the exceptional man, just as a fleet is held back by its slowest ship. But it may still be true that orderly progress dictated by circumstances is more useful—especially in the case of the United States—than a helter-skelter system would prove, in which every individual took his own head and was treated as a separate unit. That, however, is not altogether apposite to the question raised by the Atlantic article with its suggestion that where an unusual person is able and willing to pay the cost an exception should be made for his special benefit. Much depends on the practical power to do it, and more perhaps depends on the effect of doing it, in so far as concerns the morale of those for whom no exception is, or can be, asked.

COLLEGES IN THE FILMS

THERE is something mildly amusing and at the same time pertinent in the protest voiced by the Leazar Literary Society of North Carolina State College against misrepresentation of college life in moving-picture shows. This defect has been made the subject of formal resolutions by the society in question and the same were recently embodied in a letter to the editors of the New York Times, coupled with certain recommendations which it may be well to set forth here in extenso. After witnessing a performance on-the silver screen, in which the scenario dealt with life in a college as the producers conceived it to be, the startled Carolinians embodied their objections to it in the following language:

1. That athletics are usually falsely made to occupy about 80 per cent of the students' time.

2. That most of the athletic contests shown are ridiculously inaccurate, since the football captain is rarely if ever kidnapped on the night before the game; since most touchdowns are not made in the last minute of play; and since most universities have an elaborate coaching staff in addition to the sole coach shown in most motion pictures.

3. That almost invariably students are falsely shown to have an excessive interest in members of the opposite sex, and that their conduct as pictured would normally lead to expulsion from school.

4. That the wide-awake and mentally vigorous college leader, whether man or woman, is rarely the type portrayed by our leading motion-picture stars.

5. That many brilliant thinkers and teachers found on the faculties of American colleges are often grossly misrepresented by the comic "college professor."

6. That most pictures of college life are trite and obvious. The home team sometimes loses the big game of the year.

7. The many vital and dramatic situations in college life have been almost completely neglected as picturemaking material. We recommend that college pictures be written and directed by college men.

8. We recommend that since the youth of the nation imitate the speech of the college talking picture the various producers cooperate with the National Association of Teachers of Speech in achieving admirable speech standards.

There is much truth in this indictment, but of course one may not expect too much of movie magnates and should hardly take them too seriously as holding a mirror up to nature. Memory recalls a screen version of the Biblical story of Ruth and Boaz, into which the producers saw fit to interject a somewhat anomalous figure in the person of a French lieutenant in horizon blue. In another, Katherine the Great of Russia leaves the Winter Palace in an automobile. Moreover, the college film-play is almost invariably written to a formula, in which athletics is (or are) the main motif, with the maligned hero grossly slandered by the malevolent villain so that he is barred from play in a crucial game until the last three minutes—when providentially he is cleared and is empowered to spring into the line-up to make the final and decisive touchdown. As there has to be some sort of comic relief, it is pretty sure to be the downtrodden college professor, who is caricatured in the stereotyped way as a bespectacled old gentleman in whiskers with hardly wit enough to be permitted to wander at large. And of course there must be heartinterest, invariably supplied by a fair damsel with whom both the hero and villain are hopelessly in love, and who is distressingly ready to believe that the former is a secret drunkard, embezzler of athletic association funds, and so forth.

The stage collegian is probably as authentic a personage as the stage Englishman, stage Irishman, or stage Jew—and does it really make much difference to the sum total of human happiness?

TRAINING FOR BUSINESS

SURVEYS are sometimes of exaggerated importance, but usually they are interesting. One recently made of the industrial leaders of the United States has been cited by a well-known engineering firm to prove that apparently the colleges at present have a distinct superiority over what usually figures in obituary notices as "a common school education" as a preparation for advanced success in the field of business. The figures relate to 100 men directing the destinies of the most considerable business enterprises, and while something depends on the selection of the 100 it is probable enough that so many afford a trustworthy cross-section of the business structure.

It is reported that of the 100 only 22 were the products of what is somewhat rhetorically denominated "the little red schoolhouse." There were 14 who went on to secondary schools but not to college. Those who attended college were 64, and of those three took advanced degrees. It is not altogether clear from the abstract bulletin before us whether all the 64 pursued their college careers to the A.B. stage, but at least they all went to college.

Only four of the group of 100 were of foreign birth. Twenty-nine were of rural origin, and 71 hailed from communities of 5000 or over. Fully 40 came from cities of at least 100,000 population. The present ages of the men studied were such as to indicate that between 50 and 70 years the capacity for industrial leadership reaches its maximum of fruition. Only two of the 100 were between 30 and 40 years of age, and only 13 were between 40 and 50. The largest classification were in the decades 50-60 and 60-70, which contained respectively 34 and 35 men, tapering down to only 14 who were between 70 and 80, while only two remained in active affairs after the four-score years.

White-collar beginnings and blue-shirt beginnings are stated to have broken about even among the 100; but only one out of 10 could claim to have arisen to the top from the bottom in a direct line of progression.

The tabulation may not strike the reader as at all surprising, save that, extending as it does so generally to men of mature years, it reveals a rather larger num- ber of college-trained men than one might have guessed. The general movement for going to college is of a date too recent to have affected much the category of leaders now 60 years of age—or even 50.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Class Notes

Class NotesCLASS OF 1923

February 1930 By Truman T. Metzel -

Article

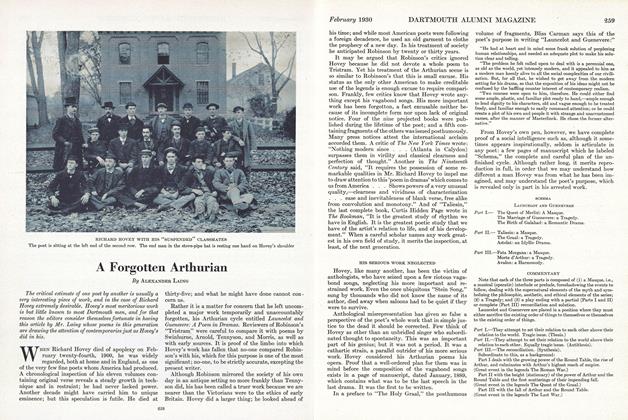

ArticleA Forgotten Arthurian

February 1930 By Alexander Laing -

Sports

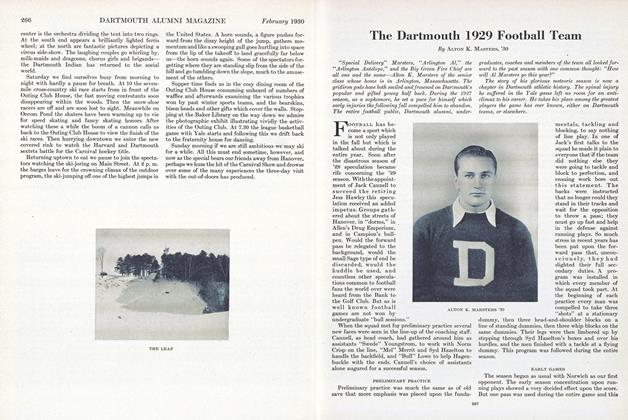

SportsThe Dartmouth 1929 Football Team

February 1930 By Alton K. Masters, '30 -

Article

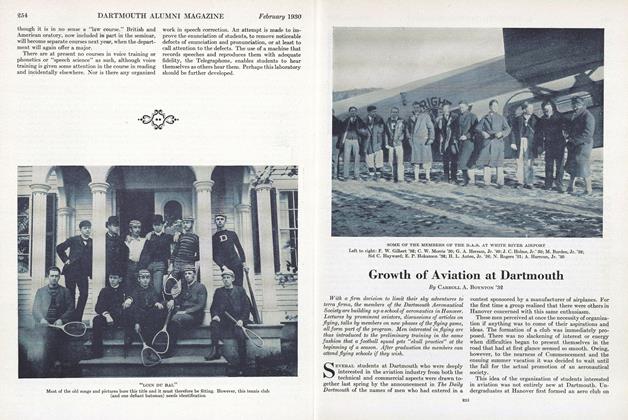

ArticleGrowth of Aviation at Dartmouth

February 1930 By Carroll A. Boynton '32 -

Class Notes

Class NotesCLASS OF 1929

February 1930 By Frederick W. Andres -

Article

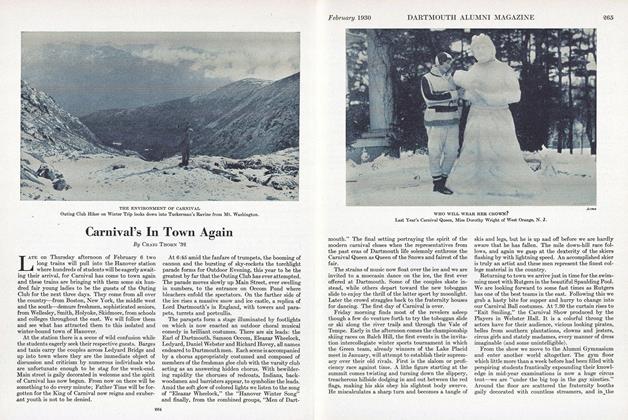

ArticleCarnival's In Town Again

February 1930 By Craig Thorn '32

Lettter from the Editor

-

Lettter from the Editor

Lettter from the EditorEditorial Comment

JANUARY 1932 -

Lettter from the Editor

Lettter from the EditorWith Other Editors

FEBRUARY 1932 -

Lettter from the Editor

Lettter from the EditorNew Hampshire Letter

APRIL 1932 -

Lettter from the Editor

Lettter from the EditorEditorial Comment

December 1932 -

Lettter from the Editor

Lettter from the Editor'Round the Girdled Earth

May 1944 -

Lettter from the Editor

Lettter from the Editor75 and Counting

OCTOBER, 1908 By Douglas Greenwood