For opinions which appear in these columns the Editors alone are responsible

THE CAMPAIGN LOOMS

EVERY year, fortunately, it becomes less necessary than in the year preceding to go into any elaborate explanation of the Alumni Fund. By this time everybody knows, about it, the functions which it performs, its necessity to the finances of the College, and the general method of its collection. No one longer needs to "sell" the idea of it to any alumnus who is disposed to consider it at all; and the number of alumni whom it has been found difficult to convince in the past has probably reached by now its lowest minimum. Wherefore we propose not to enter on any detailed explanation of the Alumni Fund, but to stress in passing one or two points which the pending campaign suggests.

Last year the quota was set at $135,000—and the quota was not reached. This was the natural consequence of conditions which arose after the figure had been established—conditions which had not been clearly foreseen. The quota was advanced to $135,000 long before the stock market crash had drawn attention so forcibly to the business depression. Whether or not the same figure would have been set had the situation been more clearly envisaged is a question—but there is room for the guess that it would have been, and that the one difference would have consisted in a slightly lessened confidence that the goal could be attained. Even as it was, the Fund netted more money for the College than in any previous year but one—a remarkable achievement, and one of infinitely more practical importance than the mere attainment of a quota.

This year the quota remains the same—$135,000— with conditions but little changed, so far as current indications go, in the business world. It has been deemed unwise to reduce it, even though at first sight it might seem rather improbable that it can be fully attained unless a distinct upward trend in the conditions of general business supervenes between now and the first of June. But the harder we try to attain it, the better will be the net result. It seems wise, certainly, to have a goal that requires an effort to reach, rather than one which could more probably be reached without much trouble. What the Fund seeks is to render the maximum of aid to the College to enable it to finish its fiscal year without resorting to red ink. For removing red-ink stains from balance sheets the Alumni Fund has already demonstrated its superior efficacy. There was a small deficit last year—the first in a long time—and it amounted to approximately the sum by which the Alumni Fund fell short of its intended quota. Hence the thing to which all energies must be directed this year is the excelling of last year's record.

By the way, it may be well to say a word of caution against exaggerating the difficulties imposed by the business situation. They are great enough as they are without magnifying them. There has been noted a propensity in all quarters to allow the adverse psychology of such a situation to operate as an exaggerating influence. It is a fact that many incomes have been curtailed—and that many others have not been affected in any appreciable degree. It has been the regrettable fashion to "feel poor" and to "talk poor" whether or not one had really suffered the loss of a single penny. The point here labored is that one shouldn't do that, and above all should avoid a defeatist attitude before this campaign begins.

The campaign itself is to be still farther shortened this year. It is felt that fully as much money can be collected if the time devoted to it is brief. We all know the Fund is coming every year. We know by this time about what we can do, as individuals. We appreciate the folly of procrastination. Why postpone? It only adds to the overhead expense to compel class agents to keep sending follow-up letters; and it is about as easy to state one's intended gift the first time as the last. The less that has to be spent on the process of collection, the more the College receives out of each dollar collected.

Possibly this is enough to say at this juncture. The watchword of the campaign may well be, "Set a watch lest the new tradition fail!" And the code message to be flown from the masthead must in any case be rather like Nelson's at Trafalgar: "Dartmouth expects every man to do his duty."

UNDERGRADUATE RELIGION

QUOTATIONS from editorial investigations conducted by the Daily Dartmouth indicate that the result has been a discovery that the undergraduate attitude toward religion is at present not so much one of hostility as of indifference, summed up in the expression "I do not care."

One has the lurking suspicion that this, if it differs in any important respect from the attitude of elders, differs mainly in being entirely candid. Moreover it is the not unnatural attitude of youth and in all probability is very much like your own attitude when you were in college, even if this was in a day when literal faith was more widespread than at present. It was what the Preacher had in mind, no doubt, when he wrote: "Remember now thy Creator in the days of thy youth, while the evil days come not, nor the years draw nigh when thou shalt say, 'I have no pleasure in them.' " In fine, not to "care" very much about such things as religion is the way of the young, who have not become fully alive to the immensity of the universe, whose cosmogony is egocentric, and whose concern for the meaning of life is scant. At twenty one takes many things for granted which later appear to lead to serious questioning.

Besides, there is room for a distinct doubt as to what is meant by "religion." The outward and visible manifestations of it vary from age to age, without very seriously altering the intangible thing within. That even a rather thoughtless undergraduate is completely devoid of religion is difficult to believe, but that such a one can readily define his own position is unlikely. That he understands by religion a crystallized creed and a visible church is probable. That he doesn't feel any burning interest is wholly natural. Comparatively few do feel such an interest until somewhat later in life— and some, of course, never.

But is it a thing for older and hopefully wiser heads to lose sleep over? The man for whom the affairs of this world are no longer engrossing usually begins to feel a belated concern for those of a possible Beyond; but the youthful collegian, with the present world bulking so large before him, is rather unlikely to be intensely occupied with speculations about still another. This may not be as it should be, but there can be little doubt that it is as it is. There seems to be no reason to question the validity of The Dartmouth's assertion that carelessness, rather than opposition, is the essential characteristic of the undergraduate attitude toward such matters. This is likely to be changed as one grows older and as the importance of mundane things lessens in the face of a broader outlook on the titanic environment of that speck of dust on which we are afloat in space. One may not be much more certain of what and where the truth is—but at least one learns to "care," incomprehensible as this may seem to the adolescent mind.

It may help for those who are older to hark back to your own college days and reflect on what your own attitude was then—and then to consider what the changes have been since your day, even in the attitude of mature minds toward what was once held to be so literally established and certain with respect to the nature and attributes of God, and with reference to the whole duty of Man. Some part of the alleged indifference of current undergraduates toward things spiritual must be charged to their early bringing up, to the influence of parents and their friends, to the spirit of the times; but most of all one may ascribe it to the nature of youth, fascinated by the immediate environment and as yet experiencing little need of awe. It will not be wholly surprising if Science—that dreaded enemy of the Church—is what ultimately brings man back to his conscious need of God, by revealing the incredible littleness of things mundane set against the majesty and mystery of creation. Is Einstein also among the prophets? For a guess, he is- and doesn't know it!

WINNOWING THE WHEAT

BY THIS time, in all probability, most of the Alumni Council rating blanks relating to applicants for admission to Dartmouth in next fall's entering class have been duly filled out and placed on file with the Director of Admissions. This work, which falls on the alumni of the College scattered about the country, constitutes one of the very important functions which alumni can and do perform with undoubted benefit to the authorities. The number enlisted in this task varies from year to year with circumstances, but is always large- The necessity of covering a very broad area in the effort to check up on the attributes and personal capacities of the applicants, apart from mere scholarship, leads to summoning a considerable army of unofficial volunteers to assist the members of the Alumni Council—on whom, in the first instance, rests the responsibility.

After several years of fruitful experience the members of the Council—especially those with a lengthy term of service behind them—have systematized this work very effectively. They receive the rating blanks in two lots— the first, and larger, allotment in December; the second in February. Most of the work is done in the Christmas holidays when the various applicants are for the most part at home on vacation, and the gaps are filled up later. In each case the idea is to have the applicant seen by an alumnus of discretion and good judgment, who reports on the general character and appearance of the boy, his personality, predilections and associations, his favorite amusements and activities, and anything else that may be important as bearing on his probable suitability to Dartmouth. It is but one more straw, but potentially important, in guiding the Director of Admissions in choosing which COO or more to select out of possibly three times that number of aspirants.

The effect of the Selective Process on the scholastic record of the recent classes has been stressed over and over again in these pages and elsewhere. The "mortality" of the later classes—the number dropped for scholastic deficiency in the first year of residence— has undergone a change little short of amazing. It is the rare thing now for a dozen new-comers to be separated from the College in the first semester, where a few years ago the numbers ran well into the 30's and above. With all the care there must inevitably be some mistakes; but the mistakes are creditably few and have probably reached the irreducible minimum.

Not all the blanks sent out are duly filed; but the percentage of those returned with no information is invariably small and failure is generally due to the fact that after a determined effort it has been impossible to cover a case here and there. The loyalty and efficiency of the alumni in cooperating in this matter year after year are impressive.

THAT WHEELOCK SHIRT

ELSEWHERE in this issue will be found a letter from a valued correspondent taking this MAGAZINE to task for an obvious misstatement concerning the alleged larceny of a shirt from Eleazar Wheelock's clothesline by miscreants unknown, in the year 1786. Inasmuch as by that year, the valiant founder of our College had been for some seven years in his grave, it is manifest that there has been a slip-up somewhere. The shirt, if stolen at all, may have been stolen but the searching sheriff was probably Eleazar, Jr. The article as printed last month appeared to be well documented, but either it erred as to those involved, or as to the date. May we add, however, to clear up a further misconception, that our critic himself errs somewhat in speaking of this MAGAZINE as "a semi-official publication of the College?" It is not such, in either a literal or semiliteral sense, as a matter of fact, although appearances might promote such a mistake. The ALUMNI MAGAZINE is published for the Alumni of Dartmouth College, under the direction of a committee of the Alumni Council; and while necessity and convenience require that its principal office shall be in Hanover, and while some of its editors are officially connected with the College, the fact remains that for the MAGAZINE the administration has no responsibility, and that its editorial conduct is a thing apart. What our critic probably has in mind is that a publication so intimately associated with Hanover and in such close touch with the official life of the College should be incapable of so egregious an error as was involved in the Wheelock shirt episode—which is true. But it seems a good opportunity to clear up the mistaken impression that it is in any way a College product, official or semi-official. This is the ALUMNI'S MAGAZINE, living on its own resources, and quite free (should such a melancholy necessity ever arise) to express honest differences of opinion concerning administrative policy.

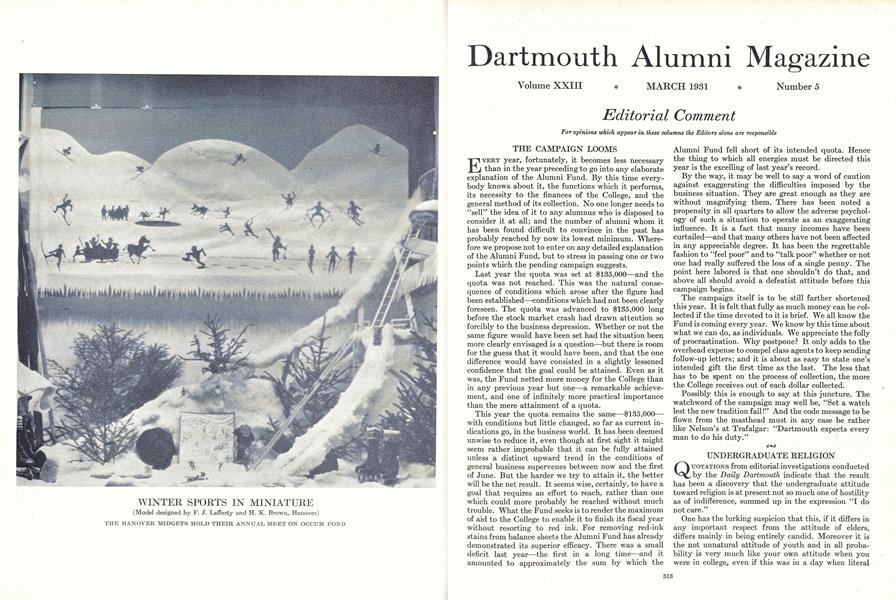

HANOVER IN WINTER

WINTER is not the time which most of us select for revisiting the Alma Mater, but it is probably unfortunate that more do not come at that seasonmore especially the older alumni, for whom winter in Hanover of old had practically no charms. The incomparable beauty of the country on a fine winter day deserves to be better appreciated by those of us who, in our student days, were wont to regard the Great White Cold as a bugbear. It never occurred to us to turn it into a festival, as is done now at the February carnival. We just stuck it out—and endured. To venture out of doors with the mercury at something like minus 20 was officially looked upon in President Bartlett's time as inviting pneumonia, and a strange European disease we were just learning to call, redundantly, "the la grippe." It was according to the best tenets of belief that sub-zero air was little short of poisonous. Even the Hanover Winter Song, trolled by the glee clubs of half a dozen New England colleges as if it were their own peculiar property, stresses only the joys of gathering about the fireside and being comfortably warm-with wassail and tobacco. That winter should be hailed with delight, and bidden a regretful good-bye when the snow gave place to March mud, never occurred to many. How things have changed!

That the alumnus who can do so should make frequent pilgrimage to Dartmouth goes without saying and requires no urgence. It is what we all do. But do we really know Hanover if we see it only in June—or in October at the foliage season? As the custom grows of keeping open all main roads throughout the snowy season, it is likely winter motor flights to the college will become less and less uncommon. At all events it would be wise, when opportunity offers, to look in on Dartmouth at the time when cold and snows prevail, if only to be impressed by the difference between then and now. What climate-cowards we used to be a generation or more ago! Fancy half the student body of 1895 belonging to an Outing Club and making cross-country trips on skis to remote skyline cabins! Such things simply weren't done; but they're done now, and it's a wholesome change.

Anybody who, in the gay '90s, had ventured to predict that Hanover's winter would come to be one of the chief allurements to draw boys to Dartmouth would have been regarded as daft. Yet it is probable that the records of Dean Bill and of his "locum," Professor Lingley, would show that this is the fact, and that more boys ascribe the winter sports of Hanover as their great reason for being attracted thither than give any other one reason—save only that arising out of preference for a country, rather than a city, college. Hanover is always lovely, of course, but never more so than in her mantle of snow. Try it—and find out! One can be infinitely more comfortable there now than in the primitive days of Hod Frary's tavern.

INNOVATIONS AT YALE

YALE now follows closely upon the University of Chicago in announcing a new course of study involving sweeping changes and designed, in the words of Dean Mendell, "to emphasize the mastery of subject and method as the aim of the Course of Study rather than the acquisition of a given number of credits." This is the latest contribution to a current period of vigorous experimentation in the colleges, with such radical curricular revisions as these on the one hand and on the other hand such revolutionizing of the social structure as Harvard and Yale are undertaking in their tremendous "house plan" developments. One feels that these changes must be largely determinative, especially in considering the millions of dollars that are being committed to them, and when the American college emerges from its present period of experimentation and flux it may appear as a unique and more or less final adaptation of permanent cultural ideals to modern needs and conditions.

The new Yale plan abandons half-year courses and mid-year examinations; it establishes three reading periods—a one-week pre-examination period and two periods of two weeks for independent study during the year in each course; it provides for annual comprehensive examinations in each course; and it includes a "four-course" provision by which capable juniors and seniors may independently do work equivalent to the fifth course, under the direction of the department of the major.

Comparison shows the Yale changes largely paralleling recent Harvard revisions. The two colleges have approximately similar reading period provisions, which Dartmouth has not tried yet, although the faculty introduced, experimentally, a three-day period for study before the recent examinations. Harvard and Dartmouth have the system of half-courses-and mid-year examinations. The Yale major calls for a minimum of four (full-year) courses in one department, to be taken in the junior or senior years; Harvard requires a minimum of from six to eight courses (half-year) in one "field," to be taken in any year; Dartmouth's system of concentration provides for a minimum of three courses (half-year) in the major study, one course in a closely related department, and the equivalent of a fifth course to be prescribed by the department of the major, in the junior and senior years. Courses for certain qualified juniors and seniors may be reduced to four at Yale, to three at Harvard; while Dartmouth has no similar provisions except for the honors students, who are generally relieved from all course requirements in their major study. Comprehensive examinations in the field of concentration will be held at the end of both the junior and senior years at Yale; whereas at Dartmouth and Harvard they are held only at the end of the senior year.

The Chicago plan, announced a few months ago, goes farther in leaving the undergraduate to his own initiative and his own devices. It allows him to proceed as rapidly as he wishes to and can. When he feels that he is prepared, he may present himself for comprehensive examinations. After successfully taking these examinations he may, if qualified, pass by comprehensive entrance examination into one of the graduate or professional schools for an advanced degree.

The Chicago plan was publicly commended recently by President Hopkins for its "liberalizing influence" and its courage in divorcing itself from "the autocracy of the departmentalized curriculum, wherein assumption is made that a man can become educated by the acquisition of a few fragmentary bits of knowledge, whether he knows anything about the articulation of these with each other or what their importance is in the body of knowledge as a whole."

The Yale changes do not go as far, or in precisely the same directions, as the revolutionary revisions at Chicago, because they are devised toward goals not altogether the same. In giving the student new freedom in order to place the initiative and the responsibility for results more squarely upon him, and in breaking down departmental lines in order to get away from the patchwork education of shreds and patches, it is perhaps less radical than the Chicago plan. But it is an important announcement, and interesting in that the Yale plan follows some of the paths and at points goes beyond the steps that Dartmouth and Princeton and others have taken toward the same ends.

SKI HAIL!

WE used to think that much of the talk about skiing being a universal pastime in Hanover was largely a myth. Too many seniors have confessed to having been on skis once during their college career, usually during their freshman year. There have been stories about going to classes on skis. But all this doubt belongs to an older regime. There has been more interest in skiing this year than ever before. There was a time when all the skiing done in Hanover was done by members of Cabin and Trail, who religiously broke out trails to the north. But that was in another time, as a brief trip over the main arteries of ski traffic toward the golf links will convince anyone.

One afternoon just after Carnival we saw 130 men on skis during a brief circuit of the ski trails that twist through The Vale. And they weren't novices. It is no longer enough to be able to slide successfully down a gentle hill. Common campus talk now includes such terms as "Stemming," "Telemark," "the Christy," and "the Gelandesprung." Proficiency in jumping and in slalom races is really becoming very common indeed. Much of this revival of interest results from the fact that since Christmas vacation there have been but five days when snow conditions were not excellent. This brand of perfect winter weather has drawn the undergraduates away from the fireplaces and sent them out over the D. O. C. trails. The entire Hanover populace has taken to skis in a big way. Every afternoon Otto Schneibs, the ski coach, gives instruction in ski turns to a class of about thirty faculty wives. There were more entries for the intra-mural carnival this year than ever before.

Probably half of the college has been on skis this winter and of this number, more than half are really skillful. So "skiing to classes" may yet be seen.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Class Notes

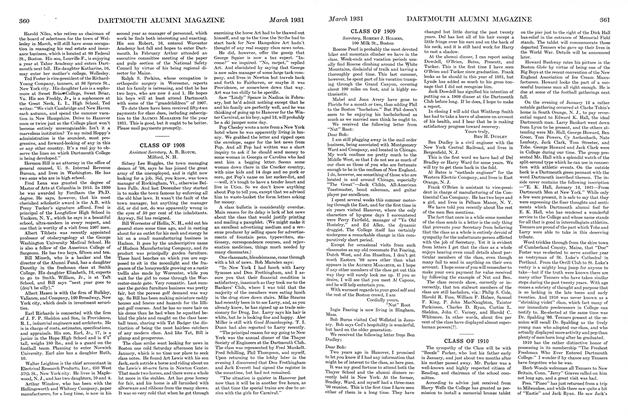

Class NotesCLASS OF 1930

March 1931 By Albert I. Dickerson -

Article

ArticleAmateur Movie Making

March 1931 By Arthur L. Gale -

Article

ArticleFebruary News of the College

March 1931 -

Article

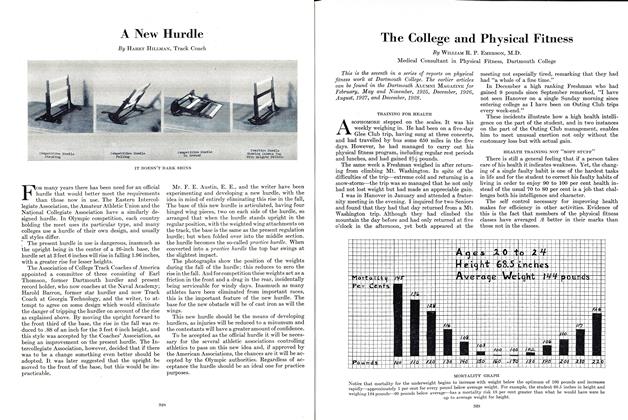

ArticleThe College and Physical Fitness

March 1931 By William R. P. Emerson, M. D. -

Class Notes

Class NotesCLASS OF 1910

March 1931 -

Class Notes

Class NotesCLASS OF 1905

March 1931 By Arthur E. McClary, Malone, N. Y., Herford N. Elliott

Lettter from the Editor

-

Lettter from the Editor

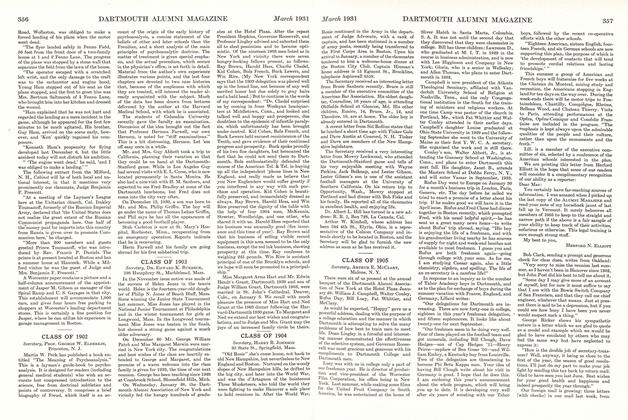

Lettter from the EditorCOMMENCEMENT 1933

June 1933 -

Lettter from the Editor

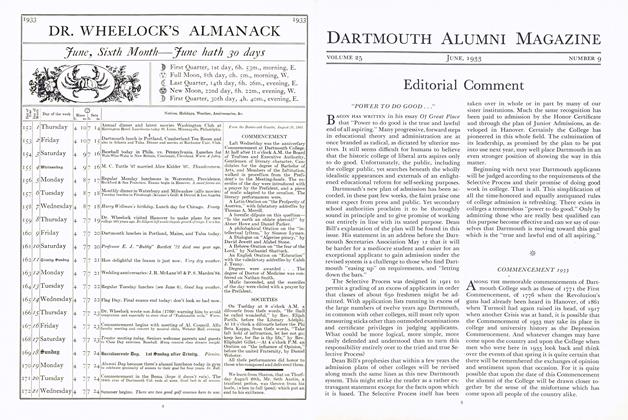

Lettter from the EditorLetters from Dartmouth Men in the Armed Forces

November 1943 -

Lettter from the Editor

Lettter from the EditorLetters

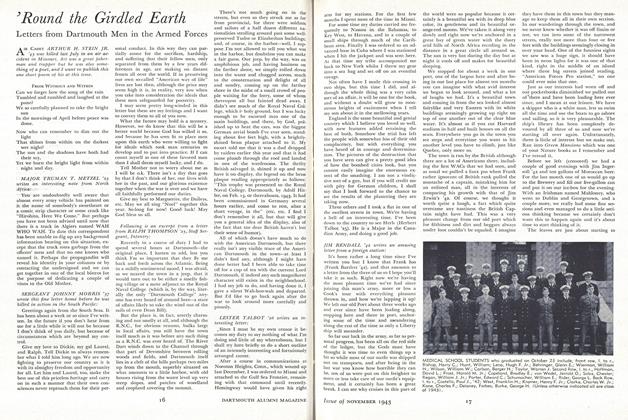

June 1945 -

Lettter from the Editor

Lettter from the EditorPress

December 1945 -

Lettter from the Editor

Lettter from the EditorVisions and Revisions

SEPTEMBER 1983 By Douglas Greenwood -

Lettter from the Editor

Lettter from the EditorThe Numbers Game

JANUARY/FEBRUARY 1985 By Douglas Greenwood