By Harold Rugg '08 and Ann Shumaker. Here is a revolutionary volume. The protestants against the formal and systematic school have found able and logical spokesmen in Professor Rugg and Miss Shumaker. The authors seem to have three major objectives: (1) to present the reader with the history and present status of the so-called educational revolution; (2) to describe the details of the functioning of a typical resconstructed school and (3) to show the need for and the wisdom of a wider adoption of the type of education fostered by the protagonists of the childcentered school who are determined to reconstruct our national education on the basis of child freedom, child activity, child initiative, and child responsibility. They are not satisfied simply to reorganize and rearrange the present motley by the current methods of swivel-chair administration and social analysis. In short, they make an appraisal of the new education which should cause American educators to pause and ponder seriously whether our current modes of reorganization are nothing more than futile administrative flourishes.

There is nothing new in the fundamental theme of the book. This theme of individualism versus socialism, of freedom versus control, is as old as civilization. All institutions have waged and are periodically waging the battle over the right of an individual to express himself, to initiate his own activities, and to education as an institution the same applies. The ancients strove over it; the reformers centered their attack about it; and even in this twentieth century it is the vital question facing American education. For the authors there is but one answer Individualism must be fostered. They rend our formal, regimented schools with wellaimed criticism and they show us in our true light as victims of the crassness of mass education.

The book is not wholly destructive. While it destroys our organization, curriculum, and methods relentlessly it offers specific measures for mending these faults, and it is here that the authors make their greatest contributions. They jest over our short units of work and offer in their place "central themes around which the whole work of the school year is developed." They strike out fiercely against our subject matter hierarchy and would replace it with "centers of interest," For example, in the third grade of the Lincoln School the pupils make a "Study of Boats." Through this project they teach phases of the following subjects: industrial arts, history, geography, arithmetic, fine arts, composition, literature, reading, science, drama, and music. But the project does more; it teaches desirable habits and skills, attitudes and appreciations, and wider ranges of general information than would obtain from ordinary subject matter instruction. They take exception to the present mode of logical curriculum organization. The new education does not propose to determine either the large outcomes or the minor details of its units of work in advance. They would prepare, however, "adequate lists of fundamental meanings, concepts, generalizations and problems of contemporary society, and the controlling themes and movements which modern civilizations are rapidly evolving."

Approximately the first half of the book is given over rather largely to these criticisms and suggested remedies. The second half is on the whole constructive. The authors set up their aims of education, "the all-round growth of the child . . . the body is to be educated as well as the mind; the rhythmic capacities, as well as the abstract intelligence. Individuality, the true outcome sought in education, is the harmonious integration of all these powers." The school, then, will have two central purposes: "tolerant understanding, adaptation to one's environment; and creative self expression." Here is system of education that actually attempts to put into practice the underlying philosophical principles of John Dewey who holds that we learn to understand and appreciate our environment by actually participating in its activities; that the progress of society advances in direct ratio as the creativeness in individuals is fostered. The authors, then, would have children invent new activities and integrate the old. They center the core of the new program around the development of capacities to create in art, in literature, in bodily development, and in drama. It is the spirit of the book, the sincerity of the authors, the clarity of their thinking, their fairness to the old education that grips the reader. No one, no matter how much he is wedded to tradition, can read this work without being definitely affected by the vigor of its arguments, the boldness of its assumptions, and the ultimate truth toward which it reaches. Educational anarchy, like anarchy within any institution, is a fearful force to contemplate, yet progress largely depends on the endeavors of a militant minority who are not satisfied with half-way measures. The book mirrors this attitude. The authors want a reconstructed, not a reorganized school. It is a brave, challenging book well worth being read by parents, teachers, and school officers, some of whom will surely gain a new spirit in attacking the grave problems in education that now face us as individuals and as a people.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Article

ArticleIndian Oratory

January 1930 By Jason Almus Russell -

Lettter from the Editor

Lettter from the EditorEditorial Comment

January 1930 -

Article

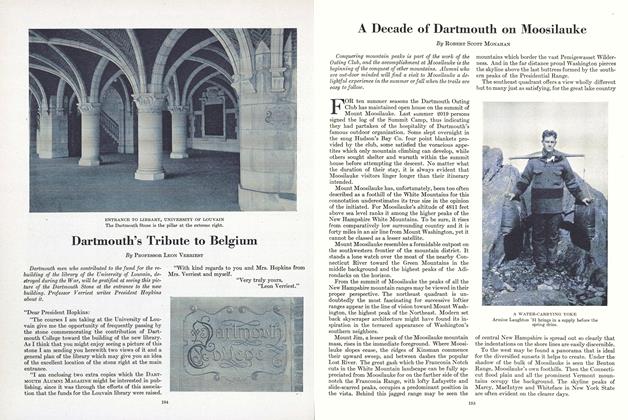

ArticleA Decade of Dartmouth on Moosilauke

January 1930 By Robert Scott Monahan -

Lettter from the Editor

Lettter from the EditorA LETTER FROM ED STOCKER

January 1930 -

Class Notes

Class NotesCLASS OF 1923

January 1930 By Truman T. Metzel -

Class Notes

Class NotesCLASS OF 1919

January 1930 By James Corliss Davis

Books

-

Books

BooksThe Congregational Churches of Vermon and their Ministry 1762-1914

June, 1915 -

Books

BooksALASKA SOURDOUGH:

February 1951 By CLIFFORD L. JORDAN '45 -

Books

BooksTHREAD OF SCARLET

May 1939 By E. P. Kelly '06 -

Books

BooksLaw of the Jungle

NOV. 1977 By JOHN S. RUSSELL JR. '38 -

Books

BooksTHE LIBERALIZATION OF AMERICAN PROTESTANTISM: A CASE IN COMPLEX ORGANIZATIONS.

MAY 1973 By RONALD M. GREEN -

Books

BooksTo Wrest an Alphabet

March 1975 By THOMAS H. VANCE