For opinions which appear in these columns the Editors alone are responsible

THE 162d YEAR BEGINS

THIS being a magazine for Dartmouth alumni rather than for freshmen, it may be less in order to stress the manifold changes which greet the eye of one coming to Hanover for the first time this fall. Nevertheless the fact that so few of us among the many thousand of our graduates have the opportunity of a frequent return to the Campus makes it not altogether inappropriate to speak of the altered appearance of some once familiar streets. Some old friends are gone. Culver, for example, has disappeared from view and where it once towered in gloomy midvictorian majesty there is a vacant lot. Does any one really sigh for Culver? Architecturally it always suggested a rural high school. Older heads will recall it as heated by stoves and permeated by the varied odors capable of being produced by a chemical laboratory. Still it had a place in our memories, whether or not we ever learned to love it.

Of less imposing effect is the sudden change of the name engraved on the facade of what was until lately the home of the Tuck school, next Robinson hall. This, since the Tuck menage has migrated to its new home nearer the river on the lower reaches of the Hitchcock estate, has blossomed out with the honored name of McNutt, commemorating one of the sincerest friends the College ever had.

Three new dormitories, named respectively Woodward, Ripley and Smith, now adorn the left-hand side of Wheelock street as one advances on the Gymnasiummanifestly new at the moment because the grading has not had time to efface its rawness, but sure to look as if they had always stood there by the time another Commencement rolls around. Can the patriotic alumnus identify, without aid, the personalities commemorated by the names of these new buildings?

At the opening of the College the enrollment revealed £lB7 students, among whom the incoming freshman class totalled 664. The number of enrolled students is stated to exceed the figure of last year by six. In view of the unfavorable industrial conditions at present prevailing throughout the world and the reflection thereof in schools and colleges everywhere, it might have been natural to look for a falling off, rather than an increaseand in fact predictions to that end were not unheard. It appears, however, that the College is filled to capacityand perhaps rather more than that. Dartmouth can handle approximately 2000 undergraduates comfortably but the pressure compels her to stretch that figure just a little every year. The faculty numbers a little more than 250.

If the natural first inquiry of every alumnus at this season of the college year relates to the size and prospects of the football squad—as experience leads us to suspect it does—shall we be too swift to blame? Do you, on awakening at the day's first beam, make inquiry as to the state of your soul? Or do you ask what sort of weather seems to prevail outside? Let's be human. We all want to know what the outlook is for the great major fall sport, and therefore we ask the first person who comes along who seems likely to be able to tell us. The answer need not concern us here, because by the time these lines are printed everybody will be pretty well aware whether the College has been able to turn out a good team or not. The point insisted on is merely that this is a perfectly legitimate interest and would better be recognized as such, rather than treated as if one ought to feel ashamed to care. There's hypocrisy enough in this world of sin without adding this bit. Hopefully not many of us regard football as the one thing Dartmouth exists for, and by no means imply that we do when we make eager inquiry in September as to the prospects for October.

So here's hoping the 162d year gets away to something like the usual good start. May it finish as well as it begins and may we all be here to see!

THE COLLEGE MIND

THE address made by the President of the College at the opening of the year was, as will be seen by any one who reads it as elsewhere printed, a noteworthy utterance. Not the Dartmouth fellowship only, but the country in general, has come to recognize in these recurrent introductory speeches of Dr. Hopkins something sure to be out of the ordinary. That the same attention is paid by leading educators and prominent newspapers to the inaugural remarks of other college presidents is hardly to be asserted; and the reason may well be that hinted at in the comment of the BostonTranscript, when it said:

"Whatever the reason for this discrimination, we think we are safe in saying that there are few college presidents who feel that the address they deliver before the undergraduate body at the formal opening of a new academic year is one of the most, if not the most, important of the year and as such should command their attention for a considerable length of time previous to its delivery. It may be because the atmosphere at President Hopkins' summer home down in Maine is especially conducive to the preparation of unusually sound and satisfying statements of educational fact and finding, or it may be because 'Hoppy,' perhaps, has just a little bit more faith than the average college head in the ability of the average undergraduate, including freshmen, to digest the fundamentals as well as the superficialities of the educational process—but, whatever may be labelled as the cause, the fact remains that the addresses which President Hopkins has delivered for the last half dozen years at the convocation which officially opens the Dartmouth year have been as thorough, as searching and as far reaching as any he has delivered anywhere before any audience later in the year."

The address this year was perhaps less striking in its output of single arresting phrases than some of those which have preceded it in recent years; but for solid content of intellectual and moral meat we doubt that it has been exceeded. The plea, over and above that which one must always make for the proper understanding of what liberal education colleges are after, was for a sounder and more comprehensive idea of what shall constitute genuine culture in this age and time. We are no longer to accept as definitive and conclusive the inherited ideas of cultivation imposed on the world by a single class—to wit, the leisured rural aristocracy, with their belittlement of industrial activities and their "scorn for greasy mechanics and chaffering merchants." Sordid though such things may be at bottom, they have brought with them some hint of beauty which it were well not to exclude from our cultural ideals. The old order changeth, yielding place to new—or at all events amplifying and extending the old, so that it may include appreciation of the material in conjunction with the intellectual and moral achievement of modern man. The Manhattan sky-line from the harbor, the Chicago lake-front, the Charles river basin—even those striding lines of steel trestles that blaze their paths across rural New England to culminate in metal forests surrounding remote transformer stations —must take their place in our concept of what may be inspiring and beautiful. A great bridge spanning the Hudson may be as noble a construction as a cathedral. In short, narrowness is the thing to avoid; and while it is undoubted that the past must always afford the background against which forthcoming ideals must be built, there would be danger in accepting as frozen and forever immutable the notions of what is and what is not to be included in the schedule of one's admirations. We are not as yet half awake to the glory incident to our engineering age, which is not all efficiency, not all dollars and cents. It is not all ugliness. There is poetry, there is music, there is romance in what is growing up around us—and Rudyard Kipling is its prophet.

It is doubtful that in recent times there has been a more genuinely eloquent utterance than is found in the paragraph in which Dr. Hopkins outlined the inspiration of the Hanover surroundings—too good to escape quotation here: "Likewise, I would insist that the man who spends four years in our north country here and does not learn to hear the melody of rustling leaves or does not learn to love the wash of the racing brooks over their rocky beds in spring, who never experiences the repose to be found on lakes and river, who has not stood enthralled upon the top of Moosilauke on a moonlight night, or has not become a worshipper of color as he has seen the sunset from one of Hanover's hills, who has not thrilled at the whiteness of the snow-clad countryside in winter or at the flaming forest colors of the fall I would insist that this man has not reached out for some of the most worth-while educational values accessible to him at Dartmouth."

What we would stress is the validity of the President's idea that the induction of a freshman class into the college estate is just as important as its ultimate dismissal; that the welcoming address should be as hopefully inspiring as the baccalaureate sermon; in fine that the invocation is as vital as the benediction. Out of the many things that the President does well it might be safe to say this is the thing he does best of all—and the outside world seems to recognize it as well as ourselves.

LAST YEAR'S ALUMNI FUND RECORD

POSSIBLY, if the magnitude of the business depression had been foreseen at the time, the decision to advance the quota of the Alumni Fund for 1930 to a total of $135,000 would have been postponed. As it was, the higher figure was adopted, and the results are before us. Detailed consideration is likely to convince any reader that, with things as they were, the outcome was amazingly creditable. Of course the quota was not secured; but it has long been the accepted theory of the Fund committee that it is of less importance to attain the quota than to get actual money for the College. What happened this year was that, although the established quota was not reached, more money was ac- tually collected for Dartmouth's use than in any previous year, save only 1929. The figures given at the close of the campaign show that $121,130.69 resulted, which is about 90 per cent of the figure taken by the overseers of the campaign as their ostensible goal. The quota, we must remember, is merely a mark to shoot at. If it is reached, it is an added gratification. If it is not reached, it is not of overwhelming importance. The main thing is to provide the College with money which it needs to balance its budget and hopefully add a little more to the principal endowment funds.

This year the money was contributed by 5418 givers out of a total of 8379 living graduates—or 65 per cent. This compares favorably with previous years and vastly exceeds the record of any other institution, great or small, which maintains a similar Alumni Fund. A recent tabulation of such funds collected in ten representative smaller colleges reveals that the most extensive one—that of Lehigh—totalled this year a little short of $119,000, from 2434 contributors. No other approaches this, or our own, in magnitude, ranging as the list does between SB,OOO and $23,000. Williams with a quota of $40,000, secured $22,296. In six of the ten cases, the total secured this year was smaller in amount than in 1929—in several instances very much less; and in three others the 1930 total was substantially the same as in the year before. Lehigh's jump (from $102,000 to $118,000 plus) is therefore the one outstanding example of increase.

Thirty-two Dartmouth classes equalled or exceeded the quota assigned them, which is exactly half the list of classes as tabulated. The remaining half varied from 97 per cent down to 40.

What is of much more importance, of course, is the year about to open. The past is over and done with. The future is alive. There is no apparent probability that things will be greatly different for the next campaign from what they were in that just closed, so far as general business conditions go. There is nothing in the record to indicate that the Dartmouth alumni are "slipping" with respect to their support of the fund, since, in distinctly adverse conditions, they came very close to doing in 1930 what they did in 1929. If the present official quota of $135,000 is retained—which may be assumed as altogether probable—an incentive will be afforded to come closer to its attainment than was possible this year. That is what quotas are for, of course, and it has long been the contention of the sponsors of the Fund that a figure that seems just a shade out of reach for the moment is desirable, rather than one that can be attained without very much effort. The College gets more money "to do with" in such a case, and that is the one great desideratum.

TRANSITION

SOMEWHERE on the long road south from Hanover, hot baked with June, there is a brief moment of agony for most of the graduates who were seniors the day before. That moment may come with the first swift drop of the road beneath The Green Lantern. It may happen on one of the long stretches down the river, when the family's chatter of graduation has been replaced by the drone of tires on the hot tar. Or it may not have happened until the yellow oak office chair got sticky in the summer heat. Or again, not until a September twilight brought the old nostalgia of the campus smelling of autumn and football.

But to most of those who are part of the new vintage of graduates, that moment comes with inexorable certainty. Into it is distilled all of the wonder and confusion that marks the transition from junior to graduate. The junior is always a member of the College. His actions are oriented by undergraduate interests. But a year later, as a senior, the hubbub of the world south of Velvet Rocks and Happy Hill, becomes very noisy and near. Its imminence begins to change his thinking. It sets the senior apart from the rest of Hanover as a sort of alien castaway. He can rarely share the cheerfully savage underclass criticism of Hanover. Thinking about your life in the next twenty years introduces a new standard of values. Hanover rarely loses lustre when this comparison takes place. More than ever, as senior memories of it become graduate dreams, the town itself assumes a kindly character of friendliness.

At no time do the elms and easy camaraderie of the campus become more vivid than when this moment of poignancy occurs. The reason for this is only in the cold order of things. The four years past are friends. The four or five decades of the future are ghostly strangers. Naturally the result is confusion, a confusion in which longing for the security of the friendly years is mixed with doubt of the unknown.

The after-effect of this moment is sometimes a dim sense of resentment against the College. The resentment, where it occurs, always springs from ignorance and wondering. And it lasts only for two or three years while the new vintage of graduates takes on the mellowness of slowly ripening maturity. As age slowly and painfully brings perspective, the service the Liberal College renders gradually becomes apparent. Just at the moment when the large majority of high school graduates blindly began the nearest and easiest apprenticeship to hand, the College permitted the individual to go apart for a space, and there to consider in ultimate terms the probabilities of the life that lay before him and what these would mean to him in later years. To each individual the College gave binoculars that let him see over time rather than space. It does not matter that this vision is always blurred by the irresponsibility of the undergraduate and, perhaps equally, by an occasional unsympathetic teacher. The importance of the Liberal College is in giving this vision at all to those, who otherwise would dedicate their lives in the blindness of environmental whimsy. There may be no visible difference except a handicap of earlier apprenticeship, between a college man and his high school competitor. There may never be any difference in any sort of mensurable terms. But the College will always have given its graduates a basis of individual freedom denied those who enter their professions immediately from high school or technical school.

It is no small thing to give a man the freedom in which he may work out his destiny unfettered by the environment the Fates may give him.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Article

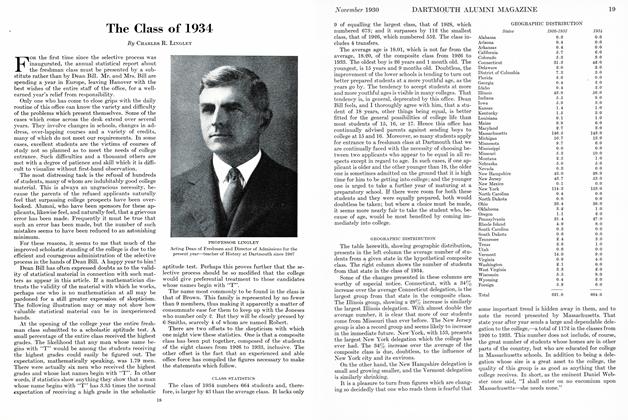

ArticleThe Class of 1934

November 1930 By Charles R. Lingley -

Class Notes

Class NotesCLASS OF 1930

November 1930 By Albert I. Dickerson -

Class Notes

Class NotesCLASS OF 1913

November 1930 By Warde Wilkins -

Class Notes

Class NotesCLASS OF 1920

November 1930 By Allan M. Cate -

Article

ArticleA Course in the Department of Biography

November 1930 By Harold E. B. Speight -

Class Notes

Class NotesCLASS OF 1910

November 1930 By Harold P. Hinman

Lettter from the Editor

-

Lettter from the Editor

Lettter from the EditorEditorial Comment

FEBRUARY 1929 -

Lettter from the Editor

Lettter from the EditorEditorial Comment

APRIL 1929 -

Lettter from the Editor

Lettter from the EditorPress

December 1945 -

Lettter from the Editor

Lettter from the EditorVisions and Revisions

SEPTEMBER 1983 By Douglas Greenwood -

Lettter from the Editor

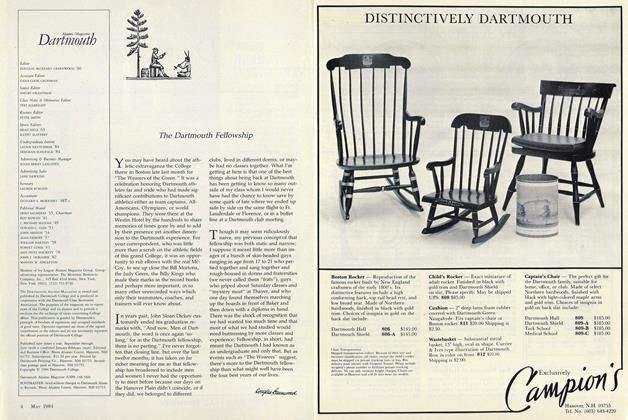

Lettter from the EditorThe Dartmouth Fellowship

MAY 1984 By Gouglas Greenwood -

Lettter from the Editor

Lettter from the EditorA CENTURY TO REMEMBER

Nov/Dec 2005 By Sean Plottner