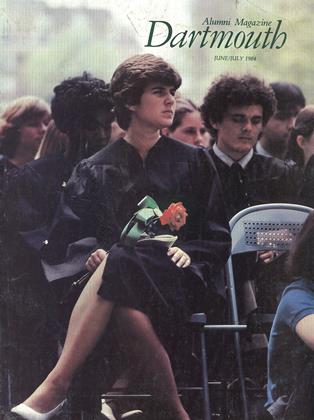

Commencement is a bittersweet time a marker in one's experience that signifies new beginnings as well as the end of something. We hear that sort of talk a lot as graduation rolls around. This is because we are ritualistic creatures, we homo sapiens, locked routinely into the practice of marking the swift passage of time with anniversaries and birthdays, fairly well "into" the "Thank-God-it's-Friday" mentality, where the week is segmented into a series of symbolic phases. (Monday, the cartoonists inform us, is to be detested; Wednesday is "hump day," the point at which the weekend looms almost close enough to be tasted; and by midFriday, the Doppler effect is at work and before we have a chance to blink, the alarm clock announces another Monday morning.)

There's also a lot of banter around Commencement about those idyllic college days, and the other side of the coin euphemistically called the "real world." Dartmouth graduates are especially prone to this simplistic dichotomy because Main Street, Balch Hill, Moosilauke, and Union Village Dam lodge in the memory and have a way of lingering there. As George O'Connell noted in these pages last fall in "The Dartmouth Disease," one major factor in Big Greenerism is the place itself. Harold Bond '42 comes to a similar conclusion in his Class Day Oration (see pages 24-27 in this issue), closing with lyrical images from "Dartmouth Undying," the song which, for many of us, is the Dartmouth signature. (It may be heretical, but there's something more appealing to me about a College "miraculously builded" in our hearts than one somewhat awkwardly embraced for the granite in our muscles and our brains.)

It seems inescapable-memories of this place-especially when you're on your way out of Hanover for a spell-down to graduate school in Boston, New Haven, Palo Alto, or Charlottesville-into the corridors of Merrill Lynch, IBM, the SEC, in the Big Apple, or D.C.-often on roads less traveled by in out-of-the-way hamlets in Maine, Idaho, or Peru. But memory has a way of playing tricks on us; while we were there, the real world was Dartmouth. It was examinations, research papers and critical essays, class recitations and more formal presentations. It was the building of friend- ships in dormitories, fraternities, sororities, and clubs, friendships which changed as we grew into them. It was, in short, the world we lived. To reduce it to the way Dartmouth Row looks when a bonfire is flickering across its white bricks is one thing, but the suggestion that the "real world" begins after Dartmouth is to annihilate four very precious years of living.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureProfessor John Stearns '16: Rara Avis Una

June | July 1984 By Eddie Chamberlain '36 -

Feature

FeatureCreativity: The Open Dance at Dartmouth

June | July 1984 By Prof. Blanche Gelfant -

Feature

FeatureWearers of the Green

June | July 1984 By Jim Kenyon -

Feature

FeatureThe Best Part of My Academic Life Here

June | July 1984 -

Feature

FeatureMaking it Happen

June | July 1984 By Peggy Sadler -

Feature

FeatureThe Quiet Good Man

June | July 1984 By Young Dawkins '72

Douglas Greenwood

-

Lettter from the Editor

Lettter from the EditorOn Being No. 1

MARCH 1984 By Douglas Greenwood -

Lettter from the Editor

Lettter from the EditorThe Numbers Game

JANUARY/FEBRUARY 1985 By Douglas Greenwood -

Lettter from the Editor

Lettter from the EditorContinuing Education

APRIL • 1985 By Douglas Greenwood -

Lettter from the Editor

Lettter from the EditorTo an old friend

NOVEMBER • 1985 By Douglas Greenwood -

Article

ArticleThe winter of our discontent

APRIL 1986 By Douglas Greenwood -

Lettter from the Editor

Lettter from the Editor"Only Connect..."

MAY 1986 By Douglas Greenwood

Lettter from the Editor

-

Lettter from the Editor

Lettter from the EditorCOMMUNICATIONS

January, 1925 -

Lettter from the Editor

Lettter from the EditorLetters to the Editor

November, 1930 -

Lettter from the Editor

Lettter from the EditorA Freshman Writes Home

October 1940 -

Lettter from the Editor

Lettter from the Editor'Round the Girdled Earth

May 1943 -

Lettter from the Editor

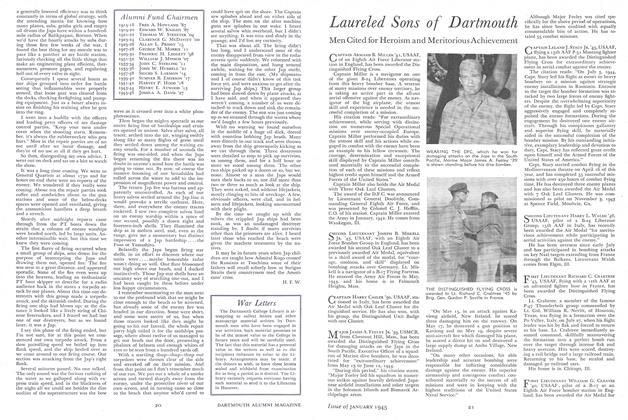

Lettter from the Editor'Round the Girdled Earth

January 1945 By H. F. W. -

Lettter from the Editor

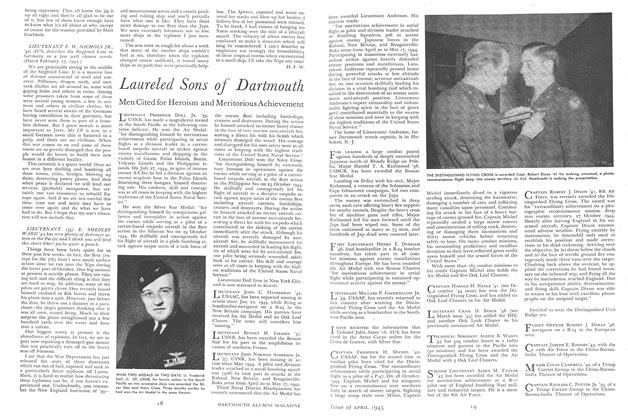

Lettter from the Editor'Round the Girdled Earth

April 1945 By H. F. W.