By Hastings Lyon and Herman Block. Pp. VIII, 885. Boston, Houghton, Mifflin and Company, 1929.

Hastings Lyon, one of the authors of this finely printed and well turned out book, is a graduate of Dartmouth in the class of 1901, and was a member of the Tuck School Faculty from 1910-1916. It is good to know that the active practice of the law has not divorced him entirely from the scholarly pursuits for which he is so well fitted.

This is the only modern, the only trustworthy and the only readable story of the life of that remarkable Englishman; who has been stamped forever by Maitland with the adjective "tough," who was not only the oracle, but the embodiment of the English law at the time of Elizabeth and the early Stuarts.

It is not an impressionistic or psychological biography nor a dry birth-to-death recital, but a series of dramatic pictures, which, taken together, give an excellent idea of the governmental and legal life of the period. All through it runs the story of the life-long antagonism between Coke and Bacon, and this, as well as the style of the writing, reminds one frequently of Beveridge's "Marshall."

The narrative is divided into five parts, dealing with Coke as boy, lawyer, judge, patriot, and writer.

In objective fashion are set before us the various phases of Coke's character; his lust for place and power; his callousness with regard to the tender family emotions; his vindictiveness and absolute ruthlessness as a prosecutor; and, on the other hand, his great learning; his ruggedness and uprightness as a judge in a day when those qualities on the bench were not too common when brought into conflict with royalty; his devotion to the law; and his unyielding courage in his old age, as a member of the House of Commons, shorn of all his earlier honors, in upholding the rights—the legal rights, as he conceived them—of Parliament, against the aggressions of Charles I. One cannot help wishing that this important part of the story had been dealt with in more detail; one gets the impression that by the time the authors reached these final chapters they felt the necessity of condensing and hurrying to a close. An unnecessary and almost tiresome fullness of detail with respect to some earlier scenes, such as the career of the Earl of Essex, and the case of Sir Thomas Overbury, might better have been spared.

The authors say (p. 194) that Coke lived in a formative period of the law. This is true only if so qualified as to relate to the very latter part of his life, and also if so interpreted as not to apply to the influence of Coke himself. Coke was essentially a conservative, and despite his advocacy of the rights of Parliament, was far from being a democrat, in any modern sense. His god was the law; and not some new and idealistic sort of law, but the law which the judges of England had been building, for upwards of three centuries. It was because he believed that the King was violating this "common law" of England that the wheel was brought full circle, and that the hard-headed old lawyer became a standard-bearer of the "progressives." If one does not press the analogy too far, the position of Elihu Root in regard to the Court of International Justice furnishes an interesting paralel.

It is astonishing, and a commentary rather on the times than on the authors, that such a book could be written without a word, scarcely a hint, of the life of the common people of England.

To how many of the young men who are "getting a legal education" and being "admitted to the bar" today is Coke anything more than an abbreviation in the title of some musty old books now seldom used? But this is the sort of book that ought to be read and pondered by all who would make the law a profession and not merely a trade.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Class Notes

Class NotesCLASS OF 1923

February 1930 By Truman T. Metzel -

Article

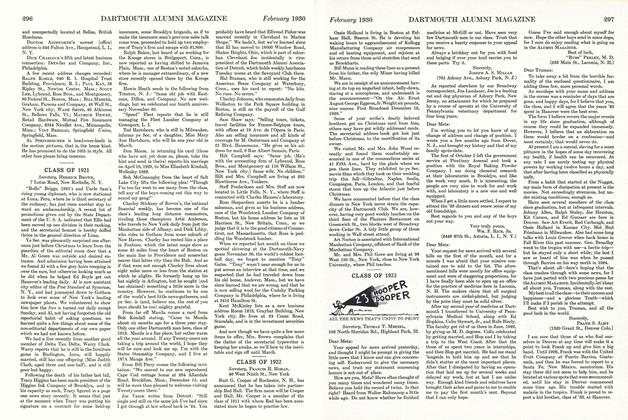

ArticleA Forgotten Arthurian

February 1930 By Alexander Laing -

Lettter from the Editor

Lettter from the EditorEditorial Comment

February 1930 -

Sports

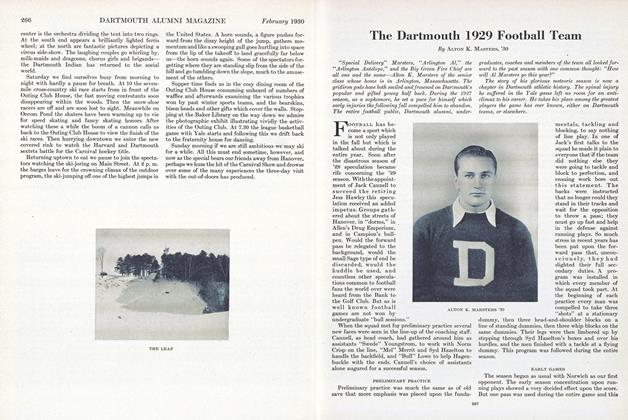

SportsThe Dartmouth 1929 Football Team

February 1930 By Alton K. Masters, '30 -

Article

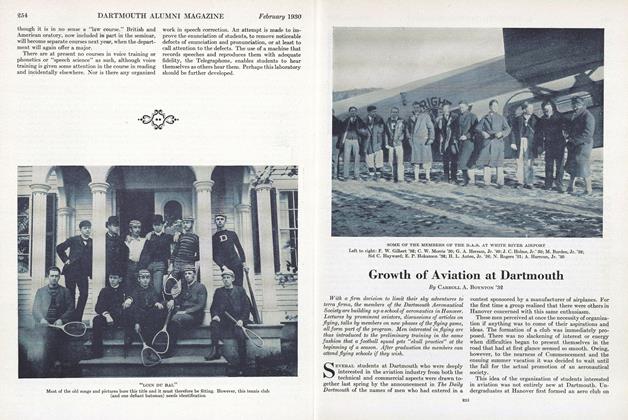

ArticleGrowth of Aviation at Dartmouth

February 1930 By Carroll A. Boynton '32 -

Class Notes

Class NotesCLASS OF 1929

February 1930 By Frederick W. Andres

James P. Richardson

-

Article

ArticleA REPORT TO THE ALUMNI

March 1921 By JAMES P. RICHARDSON -

Books

BooksTrade Associations

August 1921 By James P. Richardson -

Article

Article"Unknowns" Win Prizes

JUNE, 1928 By James P. Richardson -

Article

ArticleHanover's Socialist Party

JUNE, 1928 By James P. Richardson -

Article

ArticleAlumni Publications

AUGUST 1929 By James P. Richardson -

Books

BooksTHE FAIR RATE OF RETURN IN PUBLIC UTILITY REGULATION

October 1932 By James P. Richardson

Books

-

Books

BooksBriefly Noted

MARCH 1966 -

Books

BooksOUR WILD ORCHIDS

MAY 1930 By Charles J. Lyon -

Books

BooksCredit: Steiner

JUNE 1978 By FRANK K. KAPPLER '36 -

Books

BooksTHE ELUSIVE PLATO

JUNE 1930 By Harold E. B. Speight -

Books

BooksGUIDANCE IN CATHOLIC COLLEGES AND UNIVERSITIES. Edited

October 1949 By Howard F. Dunham '11 -

Books

BooksHENRY BARNARD'S JOURNAL OF AMERICAN EDUCATION

June 1946 By Ralph A. Burns