The Department of Sociology

If the word tradition may be applied to a succession ofrelated events which have their beginnings as late as 1893certainly the study of sociology at Dartmouth may betermed a cultural tradition. Those students who first enlisted in the study of sociology under Professor DavidCollin Wells may or may not have realized the importanceof the pioneer movement in this field of the study of "socialchange" and individual adjustment to it. But in the rushof modern life Sociology has found itself a rapidly movingscience, filling the obligation of keeping pace with the newmovements and offering a unity with the old. ProfessorWoods offers an explanation of the purpose of this department which is necessarily as full of change as is the courseof modern life itself.

THE introduction of the study of sociology into the curriculum of Dartmouth College dates from an event which was to prove epoch-making in many ways, the coming of William Jewett Tucker to the presidency in 1893. While still a professor at Andover Theological Seminary he had played a leading part in the establishment in Boston of a social settlement, the South End House, which continued the tradition of university settlements inaugurated in England by Toynbee and his associates.

Consistent with this interest of the new president in the common life of men, one of his first appointments to the Dartmouth faculty was that of Professor David Collin Wells who presently began to offer courses in the comparatively new science of sociology. At that time American Sociology was in the midst of a long continued groping for a suitable approach to the scientific study of society. Then and for years afterward a variety of one-sided interpretations held sway in this field. It is particularly noteworthy therefore that from the very outset Professor Wells gave a strongly factual turn to his instruction. Whatever the young science might become he proposed to build upon a broad and comprehensive foundation of facts. It seemed to him as it still seems to the department today that the actual customs and institutions of mankind, seen in a broad perspective of space and time, constitute the only data from which valid formulations of social processes and principles may be derived.

All institutions, whether savage or civilized, consist of a fusion of customs which have grown out of constant readjustment to the changing circumstances of living. In a generation of rapid and far-flung change like the present, when not only our own pattern of life is under- going modification, but much more the ancestral ways of those peoples upon whom the Industrial Revolution is breaking for the first time in the 20th century, in such a time the study of the nature and potentialities of cul- and cultural change can hardly be over-emphasized. The term "culture," it is perhaps unnecessary to point out, has been used increasingly in recent years to convey this major idea of the totality of a people's inherited ways of life. It is at this point that the subject of sociology finds opportunity to make its contribution.

For the purposes of instruction sociology and anthropology may be regarded as a composite science growing out of a single root, the systematic observation of the customs of mankind. We seek then to scrutinize the facts, remote, historical and contemporary, and to understand the processes by which the negligible culture of Dawn-man has lengthened and broadened into the overwhelming cultural heritage of the present day. Everywhere the circumstances of life have been in process of change, sometimes with glacier-like slowness and sometimes with the catastrophic suddenness of a volcanic eruption. And always man with that curious knack of putting two and two together (or perhaps only one and one at first), has been shaping his course and trimming his cultural sails to meet the changed conditions. Recognizable processes of adjustment and equally recognizable defenses against change have characteristically grown up in the experience of every race. The disruptive impact of crisis, the drag of custom, the progressive rift between what has been and what can continue to be, the continuing supremacy of the welladapted over the ill-adapted, the historical continuity everywhere pervading institutional development—these phenomena are always present whether the scene is a primitive or a civilized one.

It is because the realities of social change are all about us and because it is indispensible to intelligent adjustment that we learn to view such change with the objectivity of the scientific observer as well as with the intense interest of participants, that we believe the study of sociology with its processes of cultural growth is an essential part of the preparation which the college man should make for a broadened and effective life.

It is clearly not the duty of the sociologist to explore and illuminate the mechanisms of either heredity or individual response. These matters fall to the biologist and the psychologist. His own investigations concern the texture of civilization not that of the individual organism. The tensile strength of custom, the circumstances which immobilize it, the factors on the other hand which render it soluble or fluid, the dilemmas posed by the incredible and ever-growing complexity of civilized life, the relation of the various social and moral controls to the processes of change—these are some of the vital problems opening up as the result of the exploration of culture history and culture processes. And here surely is work sufficient to keep students of human society occupied for many years to come.

Space does not permit a detailed account of the courses offered in Sociology. Perhaps a simple enumeration may prove of some interest. The introductory course, prerequisite to all others in the department, is called "The Culture of Mankind—an Introduction to the Study of Sociology." It begins with a consideration of primitive culture and of cultural processes and factors. This is followed in the Junior year (in the case of Sociology majors) by a course on the development of Western culture and a fundamental course in social theory entitled "The Search for Social Law." Other advanced courses deal with social ideals,group attitudes, religion and modern culture, social ideas and trends in contemporary literature, anthropology and ethnology, crime and social maladjustment, problems of rural and urban communities and of immigration and race. A seminar course for Senior majors undertakes to coordinate the work done by these men in their three years' study of the subject. The honors men in small groups meet informally with members of the Department in the conference rooms of the Baker Library or at their instructors' homes. In all of these courses there is an enrollment of about five hundred men each semester.

Perhaps a few words should be added in regard to the aim, or as one might say, the pedagogical platform of the Department. To that end the following paragraphs, taken with certain adaptations, from a statement of policy adopted by the Social Science Division several years ago, fairly express the essential purpose of our courses.

Our object is not only to provide the student with an organized and authentic body of information, but also and primarily, to foster in his mind a sense of perspective, a profound regard for the facts, an open-minded tolerance, a willingness to consider all intelligent and candid views, and a belief in the possibility of arriving at increasingly satisfactory human understandings and adjustments.

The sense of perspective is perhaps the first requisite of an educated mind; the college-bred leaders of the future must know from what beginnings and through what ordeals civilization has been bequeathed to us, and must appreciate the meaning of the great experiments which mankind has tried. Only in this way may many futile and tragic experiences be avoided.

We believe furthermore that a reverence for the truth, combined with a critical faculty for distinguishing facts from stereotyped opinions, is of the essence of sound scholarship. The student should not be indoctrinated with a particular view regarding social policies but rather by the presentation of divergent and alternative views he should be stimulated to independent and temperate thinking and to the discovery that even widely divergent opinions nyiy include a considerable area of common ground. In brief it is our hope that from the study of sociology may come men who, in addition to a scientific mind, may also possess sympathetic insight into social problems and an unfailing disposition to undertake patient scrutiny of the facts in any situation, attitudes indispensible in bringing about better and more constructive understandings among men. And is it not because of the lack of such understandings that our modern age stands perplexed in the midst of the mechanized habitat which it has created for itself?

AFTER THE RUSH Harmony restored on the steps of Reed Hall

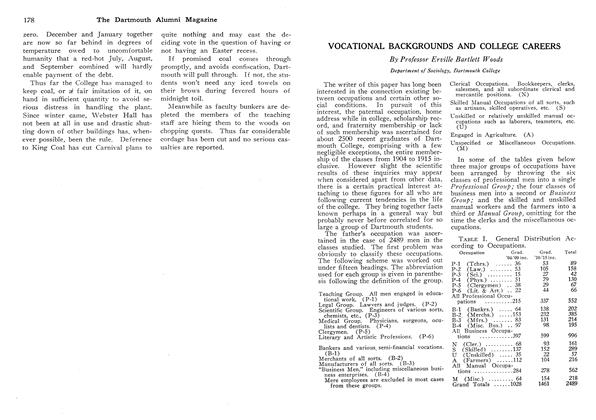

Professor

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Class Notes

Class NotesCLASS OF 1909

March 1930 By Robert J. Holmes -

Class Notes

Class NotesCLASS OF 1923

March 1930 By Truman T. Metzel -

Article

ArticleTa-Te-Tung

March 1930 By Charles E. Butler -

Lettter from the Editor

Lettter from the EditorEditorial Comment

March 1930 -

Sports

SportsFootball at Dartmouth Since the War

March 1930 By James P. Richardson -

Article

ArticleHow Carnival is Run

March 1930 By Craig Thorn

Erville Bartlett Woods

Article

-

Article

ArticleTUCK SCHOOL BUILDING TO BE REMODELLED

May 1920 -

Article

ArticleFELLOWSHIPS AWARDED FOR GRADUATE STUDY

APRIL 1928 -

Article

ArticleMath-Psychology Center

February 1960 -

Article

ArticleNorthern Exposures

DECEMBER 1997 -

Article

ArticleTHIS CANT HAPPEN TO ME

Mar/Apr 2006 By DR. MARK MCGOVERN -

Article

ArticleEverybody an Athlete

May 1929 By Harry W. Sampson