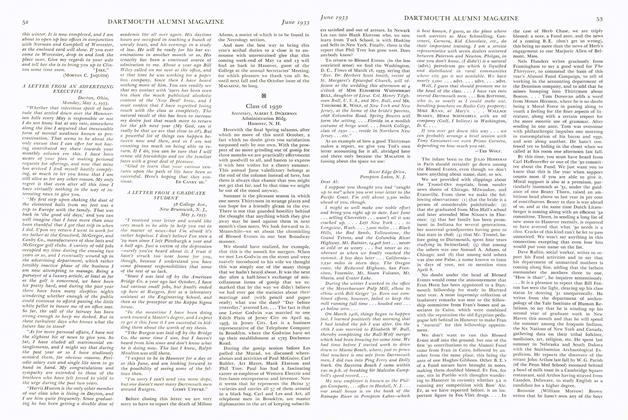

As the about-to-be host goes to the train Thursday noon to meet his Carnival guest, he feels like the boy who is about to reach the top of a Coney Island roller-coaster. It is too late to turn back now: you have to take a deep breath and plunge in. And one hardly knows whether to sit tight and hold on hard or to stand up and yell whoopee. Instead, one runs up and collects a smile, a greeting, an armful of baggage—and Carnival begins. Of course, there is always that question: will .she kiss you, or not? We never stayed around long enough to gather statistics, but the average seems discouragingly low.

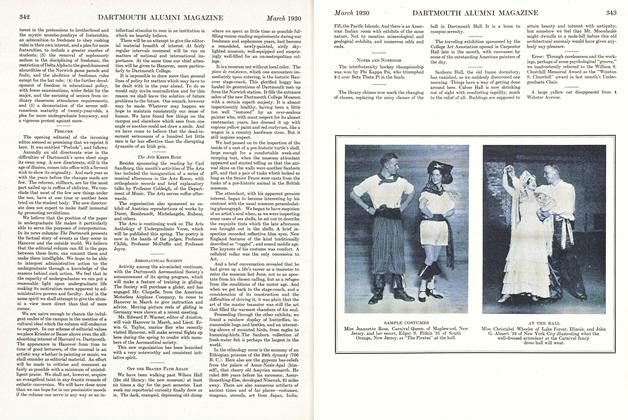

The athletic and "Big Top" elements which make up the Carnival pageantry will probably be described elsewhere in this issue. But we might say a word about the social aspects. To the men who knew Dartmouth in the Tugged regnum of the Isolated Era, Carnival must seem an exotic outgrowth, with its resort-like sartorial splurge, its spats and taxis, its to-hell-with-the-expense budget, and its frankly exotic (thank God!) females. We have tried to mentally transpose the Carnival of 1930 into the year 1900, and we find it next to impossible. In the museum there is a photograph of the Medics and their girls about to be triumphantly off on an outing in two overflowing stage-coaches. The Dartmouth man of today looks at the photograph and wonders what was the Dartmouth man's idea of fun in 1900 (or whenever it was.) Carnival, of course, is no new thing—this year's was, we believe, the twentieth. But as time has developed Carnival into a rather momentous pageant (a Stupendous Production, as one would say in Hollywood) the emphasis has tended to shift from skis, skates and snowshoes, to girls, jazz and gowns.

The Carnival Ball was supposed to be in the costume, spirit and setting of the Gay Nineties. We would gladly sacrifice our favorite and cherished toothbrush—at least that—to hear a Dartmouth man of those Gay 'Nineties who has attended Carnival say just what he thought of it. And if any alumnus of that spirited era reads this, we hope he will send in a communication.

For a comprehensive account of the Carnival of today, we refer the reader to the article in the February issue of the MAGAZINE, by Craig Thorn '32. Things Move Fast. The newly arrived guest hardly has time to spill the first installment of powder on the rug in Brother Barrett's room before she is whisked away to a tea dance. From then on, the eager Carnival couples tear around somewhat frantically in an attempt to get everything in. By the time the three-day series of changing from sport clothes to afternoon clothes to dinner clothes to evening clothes is completed, the scent of cosmetics will have so thoroughly permeated the atmosphere in Brother Barrett's room that he won't feel at home there for weeks.

As the festival wears on, more and more time is spent sitting silently in sociable stupors on fraternity house divans. One who attempts to make conversation at Carnival is soon stamped as a social misfit. One laughs, but one simply doesn't talk. One may, of course, ask the adjacent person if he or she lives in Butte. If he (or she) says yes, he does live in Butte, then one may say: "Indeed? Then of course you know Myrtle Glutz?" Beyond this, the socially successful never go.

About Saturday, one begins to secretly rejoice when the guest doesn't get dressed in time for the hockey game or the Carnival Show. The guests generally exhibit a stamina much superior to their hosts'. And when they have finally been embarked, reasonably fresh and provokingly chipper, on trains for the feminine educational centers, the exhausted host returns to sink weakly on the nearest bed.

But it is a grand old party. Everyone should try it at least once.

An innovation at this year's Carnival Ball was the admission of about a hundred stags, to introduce that certain desirable element of flux which makes the girls feel popular and the boys feel relieved. Paul Specht played for the ball.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Class Notes

Class NotesCLASS OF 1909

March 1930 By Robert J. Holmes -

Class Notes

Class NotesCLASS OF 1923

March 1930 By Truman T. Metzel -

Article

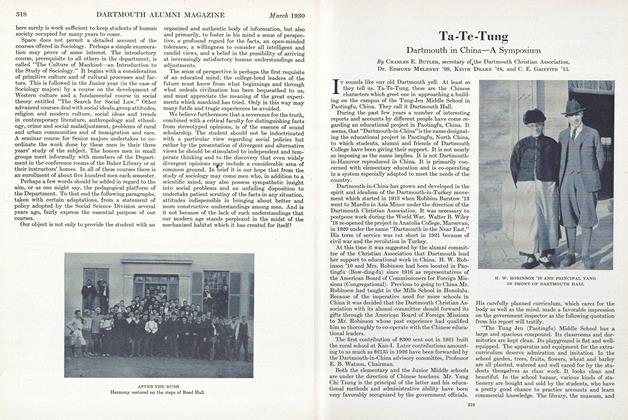

ArticleTa-Te-Tung

March 1930 By Charles E. Butler -

Lettter from the Editor

Lettter from the EditorEditorial Comment

March 1930 -

Sports

SportsFootball at Dartmouth Since the War

March 1930 By James P. Richardson -

Article

ArticleHow Carnival is Run

March 1930 By Craig Thorn

Albert I. Dickerson

-

Article

ArticleInter fraternity Council

June 1929 By Albert I. Dickerson -

Article

ArticleNOTES AND NOTHINGS

MARCH 1930 By Albert I. Dickerson -

Class Notes

Class NotesCLASS OF 1930

MARCH 1931 By Albert I. Dickerson -

Class Notes

Class NotesClass of 1930

June 1933 By Albert I. Dickerson -

Class Notes

Class NotesClass of 1930

November 1935 By Albert I. Dickerson -

Class Notes

Class Notes1930*

April 1939 By ALBERT I. DICKERSON

Article

-

Article

ArticleFINAL FIGURES RECORD ENROLLMENT OF 2,067

November, 1922 -

Article

ArticleProposed Changes in Council Constitution

May 1929 -

Article

ArticleClass Officers Weekend

JUNE 1964 -

Article

ArticleNerve Traffic

JANUARY/FEBRUARY 1983 -

Article

ArticleSTREETER HALL

May 1944 By LEON BURR RICHARDSON '00 -

Article

ArticleNewsmakers

Sept/Oct 2004 By MIKE MAHONEY '92