BALZAC, DICKENS, DOSTOEFFSKY. By STEFAN ZWEIG, translated from the German by Eden and Cedar Paul. The Viking Press, New York. 1930.

"My aim," says Stefan Zweig, in his introduction to these three essays, is—"to portray 'The Psychology of the Novelist.'" He takes for granted the reader's knowledge of the writings of the three artists and confines himself to proffering "a sublimation, a condensation, an essence."

The consequent absence of unimaginative summaries of imaginative works and of devitalizing examinations of the construction of characters is rare and welcome in a book on novelists. But his introductory regret at "having to be so concise" is amusing to one whose most frequent thought as he read the book was, "Are there any more ways he can find to reiterate that same idea?" "Concise" is what the essays most conspicuously are not. Though admirably forcible and more imaginative than such essays usually are, they are voluble, ejaculatory, vehement, eloquent, rhetorical. Sometimes the rhetoric is not only unrestrained and insufficiently precise but tawdry and bombastic.

And yet when one has finished the essays he does have a reshaped and defined sense of the mind and spirit of each of the authors that corresponds in the main with the notion their works had precipitated.

As one reads the worshipful essay on Dostoeffsky which fills considerably more than half the volume, he may be horrified at the glorification of suffering, epilepsy, and perversity, of the desire "to experience the whole sum of experience whether it be good or bad, to experience as vividly and as frenziedly as possible." He may frame sound objections to being "the servant of his impulses, the thrall of a domineering inquisitiveness concerning matters both spiritual and physical, the slave of an insatiable curiosity which scourged him forward into dangerous adventures and the thorny thicket of aberration." He may reinforce his preference for a life in the shaping of which more limited and limiting desires act with circumstance. But he may also reflect, if he has just been reading "Humanistic" essays, that Dostoeffsky surely knew much of the vast amount of life not vividly dreamt of in the new "Humanists" philosophy.

Some young people who are still capable of fresh, fundamental thinking may find that Stefan Zweig's Three Masters sets a block against the closing of their minds, particularly about the nature of great novelists and the ways their minds work, but also about the answers they are offered to perennial human questions. It contains enough thought to be the means of some. Department of English,

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Article

ArticleAlumni Associations

June 1930 -

Article

ArticleThe Dartmouth Indians

June 1930 By Leon B. Richardson -

Article

ArticleThe Use of Leisure

June 1930 By Nelson A. Rockefeller -

Article

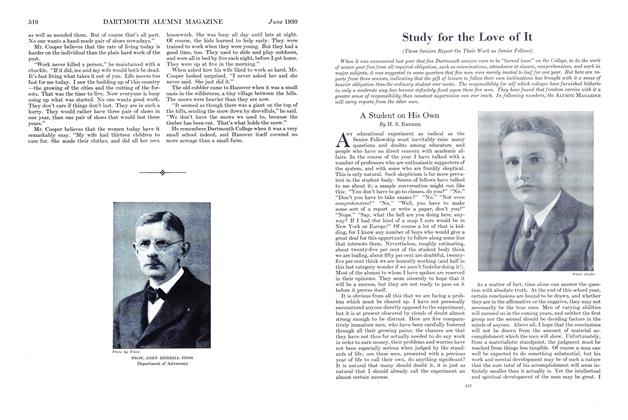

ArticleA Student on His Own

June 1930 By H. S. Embree -

Article

ArticleTrustee Meeting

June 1930 -

Lettter from the Editor

Lettter from the EditorEditorial Comment

June 1930

Sidney Cox

Books

-

Books

BooksThe November number of the Intercollegiate

JANUARY, 1928 -

Books

BooksThe Bible and Universal Pease

By B.T. MARSHALL -

Books

BooksTHE BURNING FOUNTAIN: A STUDY IN THE LANGUAGE OF SYMBOLISM.

February 1955 By F. C. FLINT -

Books

BooksAn Algebra Among Cats

October 1975 By J.H. -

Books

BooksFACULTY PUBLICATIONS

January, 1925 By Thomas G. Brown -

Books

BooksARROWS OF LIGHT

May 1935 By William H. Wood