By Regis Michaud, Harper and Brothers, New York.

With "Thoreau: The Cosmic Yankee" yet fresh in our ears, the English title of M. Michaud's life of Emerson sounds none too felicitous, and the reader may expect that he is about to open another biography of the moment, a famous life rendered palatable to the public by romantic garnishing. "Emerson: The Enraptured Yankee" is not that kind of a book. It is the product of years of intimacy spent, as M. Michaud notes in his foreword, with Emerson's books, with the scenes of his life, and with the writings of his contemporaries.

From that intimacy has grown a matured attitude, a sort of personal relation between biographer and subject, which gives richness to this study. M. Michaud says, "I have neither embellished nor added anything. I have merely dramatized, trying to feel and to reproduce the movement, the very rhythm of Emerson's life, his search for unity, his worship of thought." But the book is more than a "mere" dramatization. It is illumined by a mild and sympathetic irony. M. Michaud loves Emerson but he does not love Puritanism. He delights to contrast the austerity of the Puritan gospel of "respectability, morality, and hygiene" with the golden wantonness of Nature. What would a New England biographer of Emerson—a Holmes or an Elliot Cabot—say of the following: "On an Indian-summer night, flooded with lingering warmth, serenity, beauty, abandon, mirage, when the fields of New England were full of goldenrod and when maple woods were more resplendent than the purple of kings, Ralph was conceived."

M. Michaud can not wholly admire the idealism which kept Emerson so inviolate within the citadel of his mind, so free from the vulgar and brawling virility of young America, so immune to the passionate demand of the flesh. Of Emerson's Mediterranean tour, he exclaims mockingly, "Ralph Waldo, we love your transcendentalism, but a single prayer to divine beauty, such as was made once by Sylvestre Bonnard before the Temple of Agrigentum, would not have killed you." Elsewhere the biographer remarks trenchantly, "He loved new and generous ideas, and Utopias held no terrors for him provided that they destroyed nothing about himself." Like other writers on Emerson, O. W. Firkins and Van Wyck Brooks, Michaud is impressed by Emerson's willingness to allow others the cranks who flew to him to his own distress to make the trial of his ideas at their own expense.

M. Michaud is venturesome, and, on the whole, plausible in his speculations upon the forces which affected Emerson's life. Very masterful is his analysis of the Unitarianism of 1825, that "strange hybrid" which the ardent mind of the young minister could not long tolerate. More than earlier biographers he emphasizes the influence of Emerson's eccentric Aunt Mary Moody. "She had borne him for half a century in her womb; it was she who liad created him." And Margaret Fuller is credited in this book with having "tried to throw herself at Emerson," who was saved only by his temperamental coldness. The biographer even puts together from Emerson's writings a letter that he could be imagined as sending to discourage her advances. "There are many notes in his Journal," M. Michaud comments cryptically, "several passages in his poems, which one would gladly give to Dr. Freud."

The Journals indeed made this biography possible. No man has been more kind to his biographers than Emerson. From day to day he wrote down over a period of fifty years the adventures of his "hypocritic days." This rich store was used fully but somewhat woodenly by Emerson's official biographer, Elliot Cabot. It has remained for Van Wyck Brooks, and after him, Michaud, to use it imaginatively. In his "Emerson: Six Episodes," Van Wyck Brooks reconstructs for us the living Emerson, writing imperishable thoughts in his library or pottering ineffectually in his garden. So, likewise, Michaud in such poetic chapters as "A Day in Concord." Both of them are of course under debt to the master for their language; who can find the exact word so well as he?

The style of "Emerson: The Enraptured Yankee" deserves praise. It is elastic, vivid, and swiftly rhythmic. The author gives us, for instance, the Civil War in two sentences and Walt Whitman in a paragraph. His use of epithet is superb. He says of Channing that he was "sickeningly good," and of Thoreau that he "died on a cold caught flirting with a tree in the snow."

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Article

ArticleMy Love for Languages

August 1930 By Dr. James A.Spalding '66 -

Class Notes

Class NotesCLASS OF 1929

August 1930 By Frederick W. Andres -

Lettter from the Editor

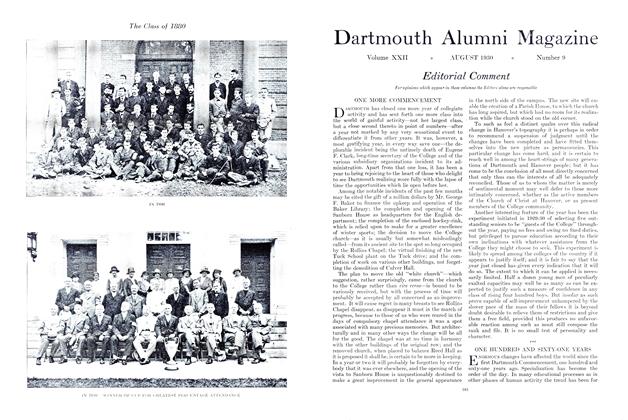

Lettter from the EditorEditorial Comment

August 1930 -

Article

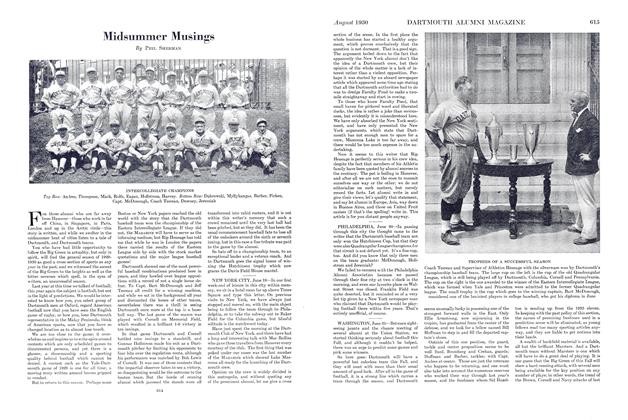

ArticleMidsummer Musings

August 1930 By Phil Sherman -

Article

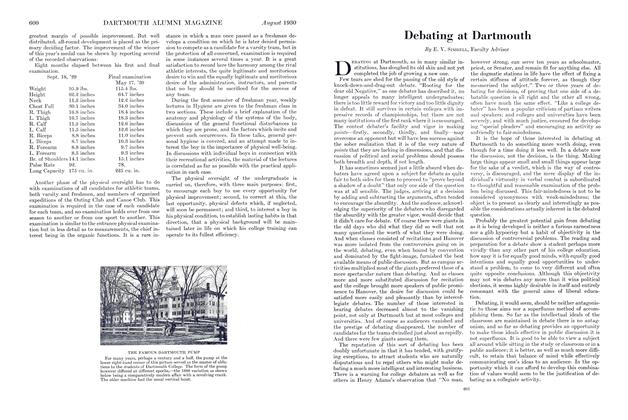

ArticleDebating at Dartmouth

August 1930 By E. V. Simrell, Faculty Advisor -

Article

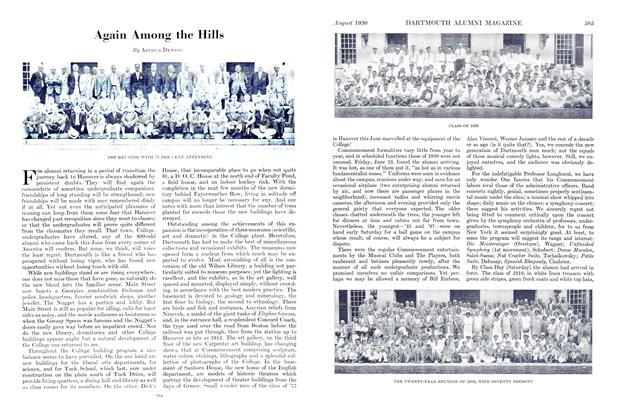

ArticleAgain Among the Hills

August 1930 By Arthur Dewing

Books

-

Books

BooksRemembering Fenway

July/August 2011 -

BOOKS

BOOKSIcon in the Family

MAY | JUNE 2021 By Elizabeth Janowski ’21 -

Books

BooksTHE CITIZEN'S GUIDE TO URBAN RENEWAL.

MARCH 1963 By H. WENTWORTH ELDREDGE -

Books

BooksFACULTY PUBLICATIONS

January 1918 By JAMES FAIRBANKS COLBY -

Books

BooksMAN OF GOD

November 1941 By Roy B. Chamberlin -

Books

BooksHOSPITAL POLICY DECISIONS PROCESS AND ACTION.

JUNE 1966 By WILLIAM L. WILSON '34