By W. Beran Wolfe '21. New York: Farrar & Rinehart, 1931. xvi 391 pages.

You may write this book down as unscientific and thus condemn it with one potent word, or you may praise it for the essential message it hides away in its pages. I choose the latter course.

President Hopkins made the following observations in his address at the opening of college this year which interest me as a psychologist and which pertain to the book under review: "Life is a blend of the art ofbeing and the science of doing. For the man who wishes his life to contribute some satisfaction to himself and to have some significance to his fellows, it is of supreme importance that he have some comprehension of the factors which have in the past reduced men from vibrant being to mere existence and which have made their efforts futile or harmful. The great leaders in the sphere of preventive medicine in their struggle to give health to the world have to know as much about disease as about well-being. It is a mistaken notion that education is concerned simply with great human achievements and with the avenues of approach to what we hold to be truth. There is profit as well in knowing why men and causes have failed and why individuals and generations have missed the highways which lead to truth." This passage will find a more detailed echo in Dr. Wolfe's book. The italicized sentence, for example, is re-written to point out the fallacy of obeying the maxim "Know thyself" unless the individual is willing to do something about it.

I never cease to marvel that so many of those who have learned the knack of understanding "why we behave like human beings" should be so inadept at choosing words to pass on their information to others. Dr. Wolfe is unfortunate, in my opinion, in calling his book a "Baedeker of the soul;" he also chooses a title that kept me from ordering the book for the college library until I had seen it; he hypothecates twelve "laws" for personality evaluation; he chooses to drag in Meckel's infamous recapitulation theory and then tries to extend it beyond its meaning to apply to mental life. These are random samples of the weak points of the book. On the other hand, however, there is a real message regarding the fine art of living; there is a flair for apt metaphorical illustration that makes difficult concepts graphically clear; the book is worth your while—but not as a scientific manual.

The essential thesis is this: man is born short of perfection to a greater or lesser degree. The causes range all the way from some very specific organic defect to some more subtle inadequacy such as poverty, the misfortunes of being an only child, or even some entirely imaginary defect. The net result of any or all such "defects" is a reaction of inferiority. The point is that as the individual develops year by year he forms a pattern oflife into which he tries to fit the entire world and its major problems of adjustment to society, to work, and to the other sex. When a defect gives rise to such feelings of inferiority, the usual reaction is to make some compensation either in that same direction or in some unrelated field. No one denies the intellectual compensation of a Steinmetz for a useless physique nor the more direct compensations of a stuttering Demosthenes, a puny child-Roosevelt, or the adult Charlie Hoff. Dr. Wolfe merely carried this doctrine to its logical conclusion, and tries to show that the individuals whom we label as neurotic, hobo or drug addict, religious fanatic or atheist, are those who have carried this compensation to a degree beyond normal expec- tation. They have "over-compensated," more or less successfully as judged by social standards. In some cases the product is recognized as genius; in others we have a dangerous social problem.

I do not purpose to review the book chap- ter by chapter. My only request is that you do not throw the book down in disgust after reading the title, or when the scientific "facts" of life seem to have been violated, or yet when the systematic working out of his thesis—with fantastic drawings—seems a bit too pat. Remember that this is meant to be a rule-book for artists, not scientists—those who find it difficult to master the fine art of living, or who are interested in those among their acquaintances who seem to be having a hard time learning to become artisians. To such I recommend the book. To others, seek ye elsewhere.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Sports

SportsModern Ski Technique

December 1931 By OTTO SCHNIEBS and JOHN W. MCCRILLIS -

Class Notes

Class NotesCLASS of 1930

December 1931 By Albert I. Dickerson -

Class Notes

Class NotesCLASS of 1931

December 1931 By Jack R. Warwick -

Article

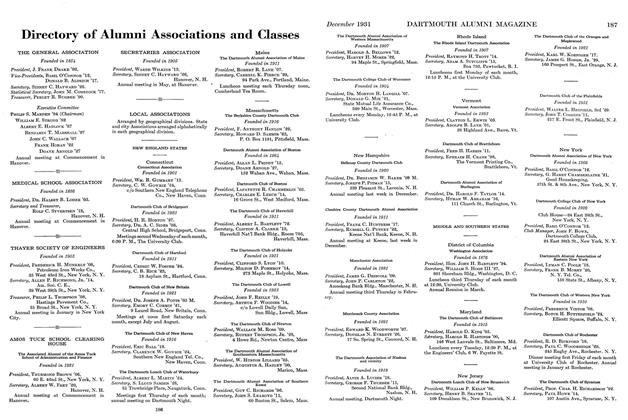

ArticleDirectory of Alumni Associations and Classes

December 1931 -

Class Notes

Class NotesCLASS of 1910

December 1931 By Harold P. Hinman -

Class Notes

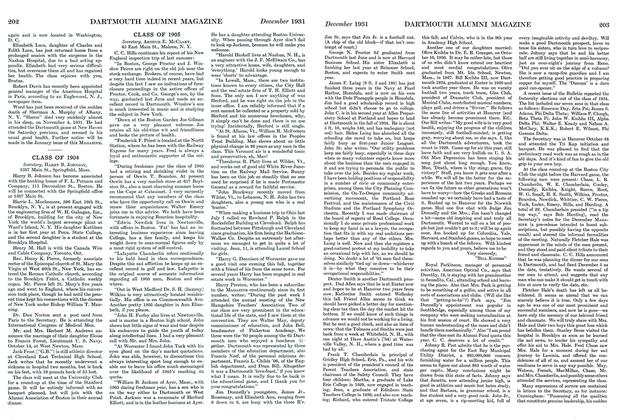

Class NotesCLASS of 1905

December 1931 By Arthur E. McClaby

C. N. Allen

Books

-

Books

BooksSamuel W. McCall, Governor of Massachusetts

November, 1916 -

Books

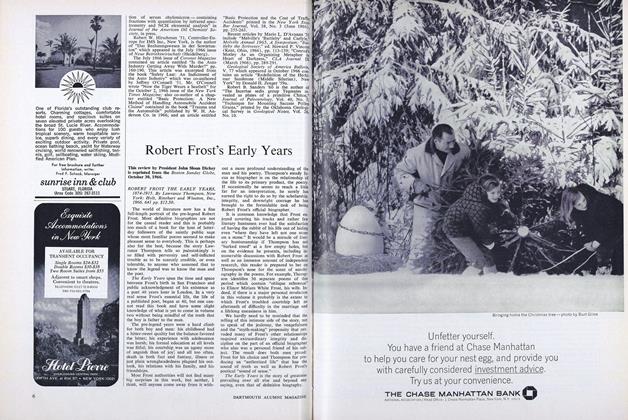

BooksROBERT FROST THE EARLY YEARS, 1874-1915.

DECEMBER 1966 -

Books

BooksShelf Life

May/June 2010 -

Books

BooksTHE FEDERAL BULLDOZER – A CRITICAL ANALYSIS OF URBAN RENEWAL, 1949-1962.

FEBRUARY 1965 By FRANK SMALLWOOD '51 -

Books

BooksADVENTURES OF A SLUM FIGHTER.

January 1956 By H. WENTWORTH ELDREDGE '31 -

Books

BooksProf. Herman Feldman

March 1943 By Herbert Wells Hill.