By Walter Beran Wolfe 'si, M.D. New York: Farrar & Rinehart, 1933. xv. 240 pp.

Again a popular presentation of a technical subject—psychiatry—comes from the imaginative pen of Dr. Wolfe. As hitherto, he expounds the particular bias of the Adlerian school of dissenters from the Freudian movement, but this time it seems to me the fault of over-simplification spoils the effectiveness of his thesis.

It is a moot question whether anything is gained by popularizing what is usually regarded as a highly specialized branch of medicine. This particular effort purports to be a handbook: to guide the general practitioner; to give the family of a hypothetical patient understanding of the causes and cure of mental ills; and to help the patient help himself. My guess is that the average general practitioner will get very little of value from the book and will react negatively (as I do) to the catagories as sketched here. The family may conceivably profit somewhat more, for the style is clear and the illustrations homely. In that very fact, however, lies the weakness of the book. For it is rather too patent to list things always in tens: 10 basic "laws of human nature"; 10 stages in a cure; the decalogue of the nervous breakdown, or 10 fundamental attributes; and 10 things for the patient to ponder—a decalogue for the patient. It is too pat. Psychiatry as a whole would never agree that the story of nervous breakdown can be thus simply told.

Having stated my reactions to the book, it remains to briefly sketch the contents. It may be that the generalizations here made are worth while, if we can forget that it is after all only one of many points of view—and not established fact. Wolfe begins with an analogy (a dangerous form of narrative or argument): a nervous breakdown is like a knock-out in the prize fight. It is nature's way of preventing more serious damage; the breakdown is nature's way of telling the patient that his behavior is getting him deeper and deeper into trouble with social living and giving him a chance to readjust himself. Fear, born of ignorance of the critical situations of life (sex, economic competition, and family) is expressed in a "body jargon" of symptoms. Three chapters of case materials (107 pages) give pointed illustration of this statement.

What of cure? Stop trying to save "face" by half measures. Meet your problems; stop worrying; don't be an extremist; set your goals within your reach; and—be your own boss.

This brief analysis may overlook one important fact; the pat statement, ignoring other aspects of the problem, may be the best for the layman. The over-simplification and the one-sidedness of it all impress the reviewer as very serious faults and make the book a disappointment.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Article

ArticleHANOVER BROWSING

December 1933 By Rees H. Bowen -

Class Notes

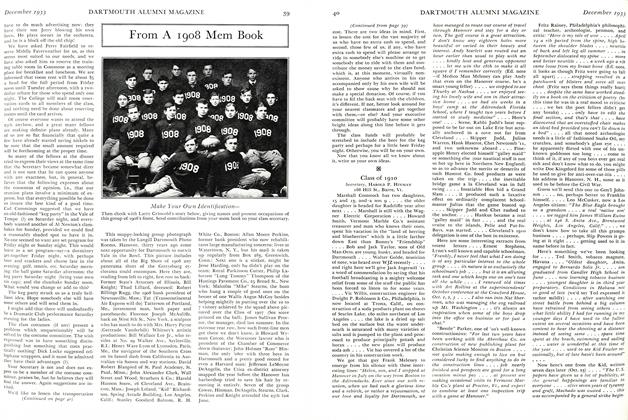

Class NotesClass of 1910

December 1933 By Harold P. Hinman -

Class Notes

Class NotesClass of 1930

December 1933 By Albert I. Dickerson -

Sports

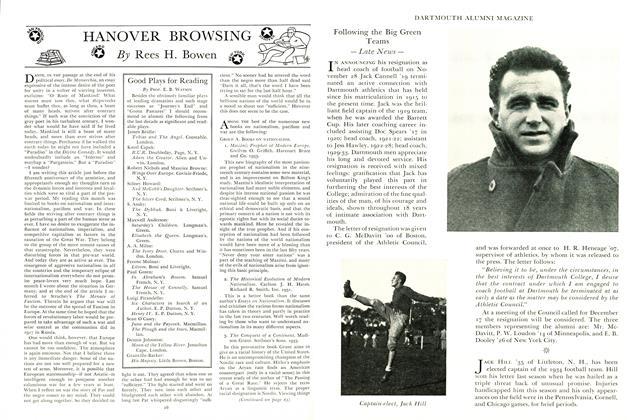

SportsFOLLOWING THE BIG GREEN TEAMS

December 1933 By C. E. Widmayer '30 -

Class Notes

Class NotesClass of 1929

December 1933 By F. William Andres, Gus Wiedenmayer -

Article

ArticleENGINEERING, A WAY OF LIFE

December 1933 By Arthur G. Tozzer '02

C. N. Allen

Books

-

Books

BooksALUMNI PUBLICATIONS

May 1921 -

Books

BooksFaculty Articles

December 1956 -

Books

BooksTHE LEDYARD CANOE CLUB OF DARTMOUTH, A HISTORY

DECEMBER 1967 By CHARLES E. BREED '51 -

Books

BooksTalking Sense

JAN./FEB. 1978 By CHARLES M. WILTSE -

Books

BooksWords of Wisdom

MAY 1984 By Peter Smith -

Books

BooksRICHARD EBERHART: SELECTED POEMS 1930-1965.

DECEMBER 1965 By ROBERTS W. FRENCH '56