By Marian King. Yale University Press, New Haven, 1931. xi 148 pp.

Here is a book that tells of the beginnings, progress, and cure of a drug psychosis—with all the appeal of truth that is more fascinating than fiction. I enjoyed it especially, for it is evidence for my thesis that many of the nervous and mental diseases are built up on a mental or psychological basis. Here Veronal was an escape from the a too-exacting world and also a method of revenging real or imagined wrongs by a spoiled child.

Marian King had a childhood filled with ghosts who had to be locked up in their closets, dolls who became alive in her playing, and Psalms and other poetry to be learned as part of her introspective delight in books and things of the world of unreality. She balanced this, to be sure, by excellence at tennis and at the sports of girls' camps.

Preparatory school meant more application to lessons that hitherto had been easy; and to cap the busy days, she began to take art lessons. Here she met a man who told her of Veronal as a means to give rest after work and to sustain one during it. She began using it to give her untroubled rest. But she later found that an overdose would upset her so that she could regard it as a revenge on her father when he crossed her in some more or less major desire. The first time was managed by the doctor, who did not tell her folks what she had done, but rather promised to get her the desired consent if she would drop the drug. Gradually, however, she found the drug became necessary again; she could not let her feelings go adequately by banging her typewriter.

The crisis of the book comes when her father over-ruled her acceptance of a position as camp couiicellor. Now she must have revenge, and so—after leaving plenty of signs telling what she had done,—she took fifty grains. She managed to escape with her life, but the consequences—a drug psychosis— were not much better than a living death. The rest of the book tells of her treatment and eventual cure in a private hospital for the insane. With the understanding of the motives for her behavior comes cure—but very slowly. The spoiled child has become socialized.

I enjoyed this book greatly; I recommend it to anyone who wishes to know why people do foolish things—why they "go insane." It takes rank with Beers' "The Mind That Found Itself," Hillyer's "Reluctantly Told," Owen's "Pick Up The Pieces," Leonard's "The Locomotive God," and Oliver's "Fear" as classic case studies. It is all truth—based on her diary and letters home. It may be read without morbid reactions.

Department of Psychology

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Class Notes

Class NotesCLASS OF 1930

June 1931 By Albert I. Dickerson -

Article

ArticleA Senior Fellow's Journey

June 1931 By John Butlin Martin, Jr. -

Class Notes

Class NotesCLASS OF 1929

June 1931 By F. W. Andres -

Article

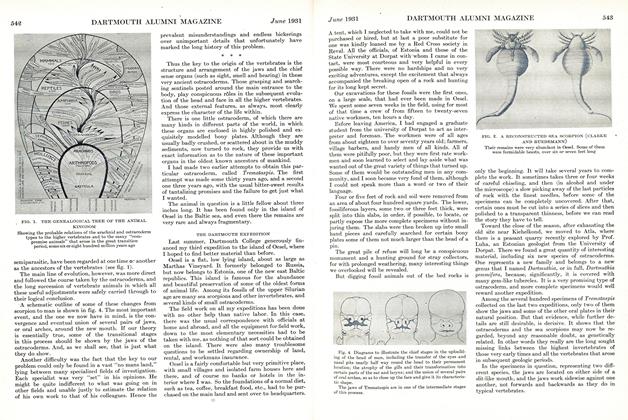

ArticleThe Dartmouth Expedition to the Island of Oesel

June 1931 By Wm. Patten -

Class Notes

Class NotesCLASS OF 1910

June 1931 -

Lettter from the Editor

Lettter from the EditorEditorial Comment

June 1931

C. N. Allen

Books

-

Books

Books"Chicago, an Experiment in Social Science Research,"

FEBRUARY 1930 -

Books

BooksAlumni Publications

February 1935 -

Books

BooksROBERT FROST THE EARLY YEARS, 1874-1915.

DECEMBER 1966 -

Books

BooksLIVING ON THE PUBLIC DEBT.

April 1945 By Bruce Knight -

Books

BooksTHIS THING CALLED FREEDOM.

DECEMBER 1970 By JOHN HURD '21 -

Books

BooksBlack Pawl

February, 1923 By W. B. P.