By R. W. Husband '26. New York: Harper & Bros. 1934. Pp. ix 654.

Mr. Average Man prefers the practical applications of Psychology to the more basic biological study of man for its own sake. Here is a book, by a former pupil, avowedly intended for both college use and for Mr. Average Man. The criteria of selection of material are important, and they are declared to be student interest, expert emphasis, and scientific validity. It is doubtful whether any two groups would agree as to the happiness of the present choice of material. Hence I merely venture a personal opinion in what follows.

If we examine content, we find the 27 chapters fall into 8 groups: vocational guidance (4 chapters); problems of personnel (8), industrial problems (3), advertising and selling (6), abnormal psychology (1), legal psychology (2), athletics and physical efficiency (2), and efficient study habits (1). The number of pages involved in each group reveals some surprising facts which seem to me to be at odds with the above criteria of selection. In the first place, problems of personnel cover 171 pages (about 26%), and problems of advertising and selling cover 161 pages (about 24%), making a good half of the book between them. This seems quite out of proportion, particularly when my own two major interests are almost ignored. Specifically, abnormal psychology is compressed into 24 pages, and child psychology is totally shut out. This seems more than a reflection on my own personal interests and not at all justified by present trends. I would agree that they are justified if the author's assumed preferences had been stated as the basis of selection. But they were not.

The general impression I gained is that the book is academic though critical, being written in elementary textbook style (headings and sub-headings 1-2-3, etc.); ancl it's heavily selective in material. This brief statement may scare off the casual reader or the practical Mr. Average Man who wants to check his business methods against the published research of Psychology. This seems to me to be the expected outcome, however, for the book is in every way a college textbook.

Turning to the content itself, the first four chapters seem to me to be out of date. The recent studies of Thorndike over a ten-year period have passed in a heavy verdict against the scientific validity of vocational guidance. By indirection, the following eight chapters on personnel are therefore brought into question. This means that over one third of the book may be questioned as failing to satisfy the third declared criterion of selection. I pass no personal verdict here; I merely point out a reasonable doubt, and a doubt which may mislead Mr. Average Man. In my experience, personnel workers are themselves more critical of this material than is Mr. Husband. The same criticism might equally well be made of the material on advertising and selling. It is a fact that Psychology today is trying to "clean house" of much of the impractical studies of appeals, use of color, size, type, etc. worked out in artificial laboratory situations divorced from any sales problem. The book gives no such hint. We no longer care what a man might do or what he thinks he thinks about a given appeal, size ratio, etc. We now want to know what his buying habits are and the conditions under which he actually bought. One of the most recent stimulating books to present this newer contribution of Psychology to this large and important field is not even listed in the many accompanying references.

To sum up, then, here is a college textbook. It will be acceptable or not according to the user's ideas as to the content and the modern evaluation of Psychology at Work.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Article

ArticleHANOVER BROWSING

May 1934 By Rees H. Bwen -

Class Notes

Class NotesClass of 1910

May 1934 By Hanrold P. Hinman -

Class Notes

Class NotesClass of 1918

May 1934 By Allan C. Gottschaldt -

Class Notes

Class NotesClass of 1905

May 1934 By Arthur E. McClary -

Class Notes

Class NotesClass of 1933

May 1934 By John S. Monagan -

Class Notes

Class NotesClass of 1929

May 1934 By F. William Andres

C. N. Allen

Books

-

Books

BooksTHE SEVEN LADY GODIVAS

January 1940 By Dr. Seuss -

Books

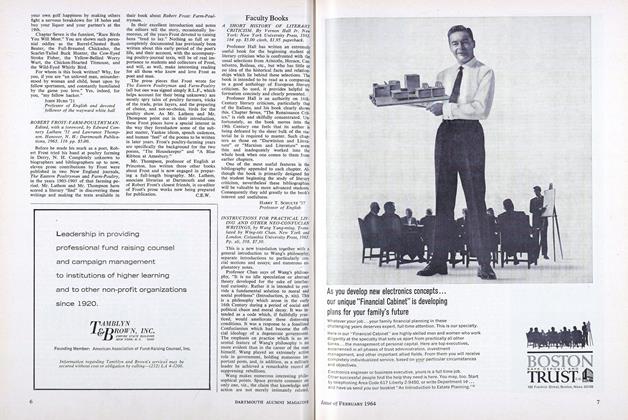

BooksA SHORT HISTORY OF LITERARY CRITICISM.

FEBRUARY 1964 By HARRY T. SCHULTZ '37 -

Books

BooksThe Private Papa

June 1981 By J. D. O'Hara Jr. '53 -

Books

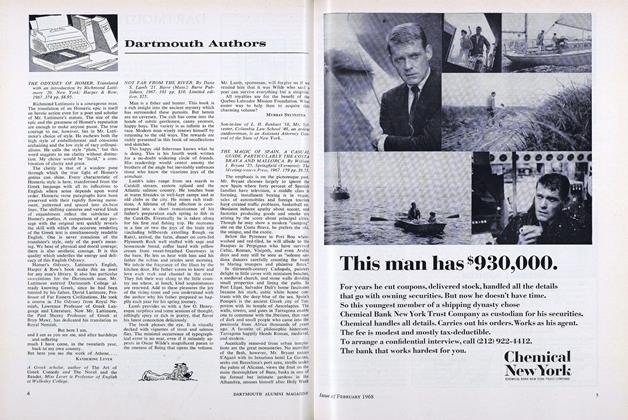

BooksTHE ODYSSEY OF HOMER.

FEBRUARY 1968 By KATHERINE LEVER -

Books

BooksSHIPS AND SUGAR: AN EVALUATION OF PUERTO RICAN OFFSHORE SHIPPING.

February 1954 By MARTIN L. LINDAHL -

Books

BooksAMERICAN INDIAN AND WHITE RELATIONS TO

July 1957 By ROBERT A. MCKENNAN '25