Medical Consultant in Physical Fitness, Dartmouth College

This is the seventh in a series of reports on physicalfitness work at Dartmouth College. The earlier articlescan be found in the Dartmouth ALUMNI MAGAZINE forFebruary, May and November, 1925, December, 1926,August, 1927, and December, 1928.

TRAINING FOE. HEALTH

A SOPHOMORE stepped on the scales. It was his weekly weighing in. He had been on a five-day Glee Club trip, having sung at three concerts, and had travelled by bus some 650 miles in the five days. However, he had managed to carry out his physical fitness program, including regular rest periods and lunches, and had gained 2½ pounds.

The same week a Freshman weighed in after returning from climbing Mt. Washington. In spite of the difficulties of the trip—extreme cold and returning in a snow-storm—the trip was so managed that he not only had not lost weight but had made an appreciable gain.

I was in Hanover in January and attended a fraternity meeting in the evening. I inquired for two Seniors and found that they had that day returned from a Mt. Washington trip. Although they had climbed the mountain the day before and had only returned at five o'clock in the afternoon, yet both appeared at the meeting not especially tired, remarking that they had had "a whale of a fine time."

In December a high ranking Freshman who had gained 9 pounds since September remarked, "I have not seen Hanover on a single Sunday morning since entering college as I have been on Outing Club trips every week-end."

These incidents illustrate how a high health intelligence on the part of the student, and in two instances on the part of the Outing Club management, enables him to meet unusual exertion not only without the customary loss but with actual gain.

HEALTH TRAINING NOT "SOFT STUFF"

There is still a general feeling that if a person takes care of his health it indicates weakness. Yet, the changing of a single faulty habit is one of the hardest tasks in life and for the student to correct his faulty habits of living in order to enjoy 90 to 100 per cent health instead of the usual 70 to 80 per cent is a job that challenges both his intelligence and character.

The self control necessary for improving health makes for efficiency in other activities. Evidence of this is the fact that members of the physical fitness classes have averaged 3 better in their marks than those not in the classes.

It is now the seventh year of our work at Dartmouth. At the beginning of each year an attempt is made to give the Freshmen a vision of optimum health and to show the possibility of attaining it during the first year in college. As a result, each year between 100 and 150 voluntarily come down to the physical fitness headquarters to be weighed in and enrolled in classes. This first group consists mainly of those who are from 15 to 40 pounds under average weight for their height— retarded in their growth and development from one to three years—and who manifest other definite signs of impaired health.. A second group consists of those seeking optimum weight for best efficiency. Each year also a considerable number of upper classmen come in for the same reasons.

This year a Senior, the editor of one of the college publications, wished to be enrolled. He remarked, "I have obtained what I was after in college activities and now I want to build up my health as I should have done Freshman year." I remarked to Monty Wells, "I think you would run better if you weighed 10 pounds more." Monty replied, "I think so too." He, therefore, put on 10 pounds and later declared, "I never ran better in my life." On the other hand, three years ago a Freshman enrolled in a physical fitness class and was advised not to try for the swimming team as he had a condition of nose and throat such that it did not seem safe for him to swim under water. However, he disregarded this advice and made his D, each year having several attacks of sinus trouble. As a Junior he regrets his D, won at the cost of impaired health.

We find that helping to pay one's way through college does not necessarily interfere with health. The average gain per week of five students who waited on table was .92 pounds as compared with an average weekly gain of .75 pounds of the physical fitness class showing the best gain, covering the same period of 12 weeks.

WEIGHT A SENSITIVE MEASURE OF THE STUDENT'SREACTION TO STRESS

The gaining of pounds is only one sign of improved health, yet it is a very accurate measure of the individual's reaction to physical and nervous fatigue, also of the effect of faulty health habits and of irregular living. The balance between the making and expending of energy is so even that weight from week to week usually is nearly stationary. The effect of any disturbing influence registers on the scales. An illustration of this appeared in regard to the relative strain of the Harvard and Yale games. For three or four years past the student body has been most interested in the Harvard game and almost invariably members of our physical fitness classes who attended that game either failed to gain or showed a loss of from one to three pounds. This year the losses at the Harvard game were comparatively few but losses in weight from the Yale game were much greater as shown by the following weight records of six men attending both games:

Student Harvard Gain Yale Loss A 0.25 lbs. 0.00 lbs. B 0.75 1.50 C 2.75 1.00 D 0.50 1.75 E 0.75 2.75 F 0.00 0.25 Net Gain 5 .00 Net Loss 7.25 Difference 12.25 pounds, an average of 2.04 pounds.

From the athletic field the student is frequently advised, "Go and get your 10, 15 or 20 pounds (as the case may be) and then come back to us when you will be in condition for further training." Repeatedly, students are also advised by their coaches, "Do your work first. Then you can come down to us free from worry and able to do your best." As regards engaging in other extra-curricular activities, this principle is less applied.

ANNUAL WEIGHING This year the weighing and measuring of the whole college showed the following results:

Annual Weighing—September, 1930

1931 1932 1933 1934 Tuck 1930 TotalNumber of Men 440 485 549 644 26 2144 Weight-heightZones % % % % % % Obese 6 5 3 4 4 5 Optimum* (22) (25) (18) (16) (15) (20) Safety 45 51 48 41 50 45 Borderline 28 24 22 25 23 25 Danger 21 20 27 30 23 25 Total 100 100 100 100 100 100

*This includes those in the Safety Zone who are from 5 to 15 per cent above average.

Note the decrease from Freshman to Senior year in the number of those underweight and the increase of those in the Optimum Zone.

It is a disturbing fact that students coming from preparatory schools show no less number of the seriously physically unfit than seven years ago. They may be better fitted scholastically but if we look for an improvement in their physical condition it does not appear and there seems to be little chance that there will be an improvement until the preparatory school changes its point of view and considers that it is of fundamental importance in a boy's life that he graduate both physically and scholastically fit. In the private school the boy is taken from his home and his health is entrusted to the care of the school. In the larger schools this care must rest for the most part with the physical director who has little power to modify pressure brought upon the boy by school requirements as regards hours of study, recreation and activities other than those of athletics. The most that he can do is to try to protect the boy from the pressure of athletic competition that has resulted in so many spoiled school athletes. As a result, even with our selective admission where boys come with a fairly even distribution from all parts of the country, we still find 31 per cent physically unfit according to the weight-height measurement which, although not infallible, is the most reliable single measure of impaired health.

Two Freshmen from the same school were weighed in. One was 29 pounds and the other 33 pounds underweight for height. Both boys were retarded in their growth and in physically poor condition. Further than this, they were only 16 years old. They were evidently selected because of their unusual scholastic ability. Asked if they were interested in following our program, they replied, "We had our choice of colleges and have come to Dartmouth for this very reason." That is, these boys had chosen Dartmouth in order to correct impaired physical conditions which should have been attended to during their preparatory school course.*

A boy at 16 is still in the period of rapid growth, too young to assume the responsibilities of college life. If there is disagreement in this opinion as regards age, there should be no lack of agreement that in any event he should be brought up to standard before he is admitted to college. It is a noteworthy fact that the private school having the boy under its entire care from two to four years thus far has produced no better condition of health than we find elsewhere. The Senior classes in five prominent preparatory schools showed worse weight-height conditions than we find among the Dartmouth Freshmen, evidence that our selective system finds the better all-around man is less likely to belong to the seriously underweight group.

PHYSICAL FITNESS AND THE BUSINESS EXECUTIVE

It is becoming more and more generally understood that impaired health brings a direct loss to industry from impaired efficiency of the worker. It should also be recognized that the causes of impaired health affect the higher powers of the mind first. For example, the judgment of the business executive who has gone stale is not to be trusted. He has lost his sense of proportion; he is irritable; people get on his nerves; his defense reaction is set up. He has lost his initiative and ability to think. It is, therefore, as necessary in business to train for health as it is in athletics.

The business executive not only needs to know about his own health but also about the condition of health of his subordinates—the effect of the more Serious kinds of physical defects, of irregular habits of living, of overfatigue, of faulty food and food habits. In other words, efficiency in business is so closely related to optimum health that a more accurate knowledge of the effect of the various causes of impaired health should be more thoroughly understood by employer and employee in order that the enormous waste due to sickness and a low standard of health may be eliminated. Such knowledge is essential in planning conditions both physical and mental under which work in industry is to be done. Such health intelligence is a fundamental factor in successful administration.

TUCK SCHOOL OF BUSINESS ADMINISTRATION

The Tuck School man in utilizing his fourth year in the college as the first year of the Business Administration course finds himself in the difficult situation of undertaking to carry on professional studies while still a member of the college. This work is of necessity more exacting than that of the regular college. His tendency is to continue his college life as usual, attempting by working far into the night to cover additional requirements. He soon finds his working efficiency impaired by irregular hours of sleep, late hours, lack of time for proper exercise and other faulty health habits.* The health habits of 73 First-year Tuck men, whose health habits were also taken the first year in the college, are as given in table at top of next column.

Faulty Health Habits No. Per Cent Irregular bedtime 64 88 No regular rest periods 61 84 Inadequate vacations or weekly rest 47 64 Fast eating or washing food down 37 51 Insufficient exercise or outdoor sunlight 34 42 Irregular time of bowel movement 29 40 Irregular habits of living 29 40 Habits injurious to health 27 37 Worry and fretfulness 22 30 Excessive tea, coffee or tobacco 21 29 Eating when overtired 17 23 Working in poor air above 68° 16 22 Overdoing at work or play 15 21 Finicky about food 11 15 Removable physical defects uncorrected 11 15 Habitual overeating or undereating 10 14 Uncontrolled likes and dislikes 9 13 Candy or sweets between meals 7 9 Irregular mealtimes 3 4 Sleeping with windows closed 1 1

COMPARISON WITH 1927

In comparison with, the 1927 results the faulty habits having higher percentages are as follows:

THE COMPARISON

Faulty Health Habits 1937 1930 % % Insufficient exercise or outdoor sunlight 8 42 Inadequate vacations or weekly rest 27 64 Irregular bedtime 49 88 No regular rest periods 41 84 Irregular habits of living 27 40 Habits injurious to health 25 37 Worry and fretfulness 27 30 Working in poor air above 68° 3 22 Excessive tea, coffee or tobacco 7 29

It will be seen that faulty habits which might be called "pressure habits" have increased to a marked degree and present very clearly a definite problem for their correction if the student wishes to maintain efficiency.

The health habits showing the most improvement had to do with overdoing and food as follows:

Faulty Health Habits 1927 1930% % Overdoing at work or play 27 21 Fast eating or washing food down 59 51 Candy or sweets between meals 23 9

The problem of the student of Business Administration is the same as that of other professional men: namely, that of carrying on work not at the expense of impaired health but with an improvement in both physical and mental condition.

MORTALITY AND MORBIDITY OF THE PHYSICALLY UNFIT

The laws of health are as inexorable as other laws of nature and when we transgress them we must pay the penalty by impaired health, by increased sickness and by earlier death. The fact that we do not always appreciate the immediate effect of violating these laws does not make the result any less certain. The following table shows the relationship between sickness and weight:

Days of Sickness* September, 1929-May 1, 1930Weight-height Average Days of Sickness per CaseZones Freshmen Sophomores Juniors Seniors Obese 6.6 3.0 2.1 1.5 Safety 5.6 3.8 2.9 2.4 Borderline 4.7 3.0 2.9 2.7 Danger 5.7 3.9 3.2 3.6 Total 5.5 3.6 2.9 2.8

*Including respiratory and digestive groups

Note the higher average number of days of sickness in the Danger Zone for all classes; also the decrease in days of sickness from Freshman to Seniors.

An estimate of the mortality risk of the seriously underweight group in the college on the basis of the accompanying actuarial table shows 16 per cent greater risk on the average than occurs in the Safety-weight Zone. As regards the factor of age, the younger the individual the higher the mortality.

LENGTH OF HUMAN LIFE

Due to higher health intelligence as applied during the first decade, the span of human life has been increased during the last half century about 12 years. However, after the age of 30 there has been no increase. On the contrary, Professor Forsyth states that the length of life in this country is actually decreasing and that the great gains at the early ages are already more than offset by the losses at advanced ages. In the first decade life has been prolonged chiefly by the removal of the five causes of impaired health: namely, physical defects, irregularity in living, overfatigue, faulty food and health habits. The removal of these same causes during the later period of growth—that is, in school and college—would have the same effect of prolonging life and efficiency some 10 or 15 years. Herein lies the significance of Dartmouth's physical fitness work.

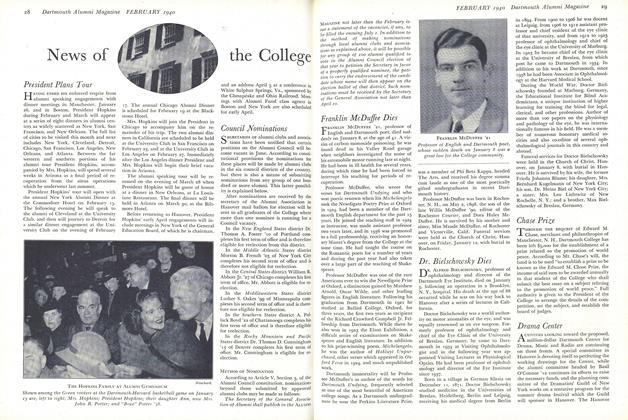

MORTALITY GRAPH Notice that mortality for the underweight begins to increase with weight below the optimum of 160 pounds and increases rapidly—approximately 1 per cent for every pound below average weight. For example, the student 68.5 inches in height and weighing 124 pounds—20 pounds below average—has a mortality risk 18 per cent greater than what he would have were he up to average weight for height.

MONTY WINS BY 10 POUNDS

A STUDENT WEIGHING IN

*While this article was. being written, a gifted boy came in from one of our leading preparatory schools. His program was one of continuous study and recitation periods, with one short recess, from 8:00 until 1:00 when he had his midday meal. From 1:45 to 2:15 he was training for the high jump. Asked why he had such severe exercise so soon after eating, he replied, "There are so many men to be coached in athletics that it is necessary to begin early in order to take care of the whole school in time for recitations at 4:30." This boy was in the most rapid period of growth and his symptoms were those of chronic fatigue. Three days later a fifteen-year-old boy from a Junior High School in metropolitan Boston reported the following program: His school began at 8:80. He had six 50-minute recitation periods to 2:10, allowing him 15 minutes for his midday meal. Although he was a fast eater, this did not allow him time enough to eat all he wanted. The lunches were served at three different periods but his schedule was such that on no successive days did he have lunch at the same hour. His subjects compelled him to have six recitations every day except Thursday, when he had two study periods. This boy was 25 pounds (26 per cent) underweight for his height. His parents had become anxious about him because he was so easily tired and because he had made no gain in the four months since school began in September.

*In checking up the programs of First-year Tuck men for three consecutive days, the findings were as follows: As regards exercise, 24 per cent took no exercise in the 3 days and only about one-half exercised in the open air 1 day out of 3. The kinds of exercise taken were: touch football, handball, basketball, hiking, skating (including hockey), swimming (including water polo), boxing, gymnasium, dancing. It will be noticed that 6 out of the 9 kinds of exercise listed were indoor. The amount of exercise per day varied from 15 minutes to 434 hours. The new House Plan of the Tuck School enables a man to be indoors continuously, one man reporting the actual time spent out-of-doors as 6 minutes in 24 hours. As regards late hours—any time after 12 o'clock being considered late—out of 132 nights reported on 34 (25%) bedtimes were late. One man's retiring hours were 1:30, 12:30 and 1:45. Late hours were apt to mean late breakfasts. The effect of late hours on breakfasts was evident in that 6 per cent of the breakfasts were late and 10 per cent were omitted entirely.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Class Notes

Class NotesCLASS OF 1930

March 1931 By Albert I. Dickerson -

Lettter from the Editor

Lettter from the EditorEditorial Comment

March 1931 -

Article

ArticleAmateur Movie Making

March 1931 By Arthur L. Gale -

Article

ArticleFebruary News of the College

March 1931 -

Class Notes

Class NotesCLASS OF 1910

March 1931 -

Class Notes

Class NotesCLASS OF 1905

March 1931 By Arthur E. McClary, Malone, N. Y., Herford N. Elliott