1890-1930. By Fred Lewis Pattee '88. The Century Company.

Professor Pattee's new book is a continuation up to the present time, with some inevitable over-lapping, of his "History of American Literature since 1870." The book is precisely what the author calls it in his introduction—"pioneer work." To quote: "My study of a period so near us, with, in some cases, practically no perspective, cannot hope to arrive at final values. Someone must do the pioneer work with a new period, mapping—crudely it may be, yet the best he can with the materials at hand—the new trails. Someone must do it. Let others in later years with more perspective and fuller materials correct my outlines."

The author states his thesis as follows: "The volume is built upon the general thesis that the thirty or forty years since the 1890 decade constitute a distinct and well-rounded period in American literary history, that literature during this single generation of marvelous change departed so widely from all that had gone before that it stands alone and unique, that the soul of it and the driving power of it were born in the new areas beyond the Alleghenies, and that during its thirty or forty years was produced the greater bulk of those writings that we may call distinctively our own, work peculiarly to be called American literature."

Certain of the chapter headings: Chicago, The Emergence of Indiana, The Indian Summer of Waverley Romance, The Decade of the Strenuous Life, The Feminine Novel, Revolt from the Frontier, The Poetry Debacle, The New Biography, Newspaper Byproducts, indicate the scope and design of the book. Whole chapters are devoted to Frank Norris, Stephen Crane, Jack London, O. Henry, Theodore Dreiser, and Mencken. Ghosts, not yet old, however forgotten, confront us once more: Mr. Dooley talks again to Hennessey, Edgar Saltus labors at his second-hand decadence, Theron Ware mournfully waves down the years to the Rev. Elmer Gantry, Richard Carvel summons his peers to the pleasant costume party, Richard Harding Davis comes again with his warribbons and his reporter's note book, and from the White House thunders the good tough epithet Muck-Rakers!

Professor Pattee attempts no such philosophical interpretation of a country or an era through its literature as was the air of Professor Parrington for instance but he charts useful trails and clears many areas of lush and, in one or two cases, rank, wilderness. The impression made by the book is one of profusion and vitality. Professor Pattee is a liberal-handed pioneer, fortunately free from academic snobbishness. He gives good measure to the writers of literature of the "middle layer"—Gene Stratton Porter, Harold Bell Wright, Edgar Guest—curiously enough he includes Edna Eerber in the group—recognizing their significance in the lives of millions of people. There are few phases of recent literary activity that he does not touch upon—the columnists, the humanists, Harpers' fiction prize contests, the detective novel, the father, or mother of which, by the way, he finds to be Gertrude Atherton, "pioneer in many fictional areas." There is an admirable chapter on Revaluations in which the author treats certain reversals of values that have taken place in the present era, certain commandeerings of "leadership from the forgotten," as in the case of Herman Melville and Ambrose Bierce. There is a striking study of Jack London, perhaps the best single study in the book. And for almost the first time a writer from the faculties gives full credit to the enormous influence that Mencken has had upon his time.

The work that Professor Pattee has attempted is too big really for a single volume. At times, in spite of the best efforts of the author, the book takes on the nature of a hand book. Again and again one feels like crying out "Stop a moment. Go deeper. Fuller treatment. More detail." But the limits of space are inexorable. It must be remembered again that this is pioneer work, appalling in its magnitude. And, what is most important, there is ever present in the book Professor Pattee's conception of literature as a live, uncloistered thing. This shapes his attitudes, lends cohesion to elements that must otherwise appear isolated, and gives distinction to the entire work.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Class Notes

Class NotesCLASS OF 1930

March 1931 By Albert I. Dickerson -

Lettter from the Editor

Lettter from the EditorEditorial Comment

March 1931 -

Article

ArticleAmateur Movie Making

March 1931 By Arthur L. Gale -

Article

ArticleFebruary News of the College

March 1931 -

Article

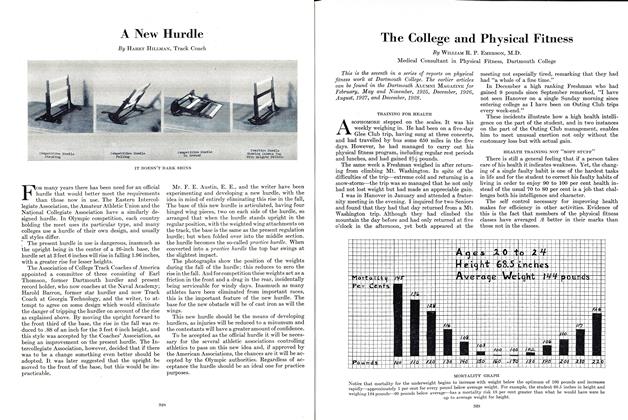

ArticleThe College and Physical Fitness

March 1931 By William R. P. Emerson, M. D. -

Class Notes

Class NotesCLASS OF 1910

March 1931

Books

-

Books

BooksFaculty Notes

February 1947 -

Books

BooksAlumni Articles

MARCH 1973 -

Books

BooksShelflife

May/June 2009 -

Books

BooksOUR FLIGHT TO ADVENTURE.

January 1957 By JOHN B. STEARNS '16 -

Books

BooksTHE GETTYSBURG CAMPAIGN, A STUDY IN COMMAND.

DECEMBER 1968 By LOUIS MORTON -

Books

BooksGREAT ENTERPRISE: GROWTH AND BEHAVIOR OF THE BIG CORPORATION.

April 1956 By WILLIAM A. CARTER