THE ROYAL FACTS OF LIFE:

Biology and Politics in Sixteenth-Century Europe by Mark Hansen '78 Scarecrow Press, 1980. 353 pp. $16

In any form of government the transfer of political power from one individual or generation to another is a question of overriding concern. By the 16th century, when monarchies had emerged from the various feudal systems of government in Europe, succession to power had become legitimated. The principle upon which it was based had become heredity. Conse- quently, a few established, dynastic families began to exercise political dominance.

Though it was based on the assumption that attributes of leadership would be transmitted to progeny, for the dynastic families hereditary succession had an obvious practical advantage: It kept the power and perquisites of rule within the family. In the ruling dynasties, once founded, this naturally led to an intense, often obsessive concern with maintaining direct continuity in the royal line. Two inextricably linked biological facts, however, made such continuity an elusive goal: the genetic laws of heredity, and the frequent inability of monarchical parents to produce male heirs who would succeed to rule according to the principle of primogeniture. We now know that the political concept of hereditary succession makes no biological sense; it is impossible for a dynasty, generation after generation, to produce a succession of heirs who are equally competent in the exercise of monarchical duties.

Mark Hansen has admirably surveyed such issues as they were manifested in the lives of members of four royal dynasties in the 16th century: the Houses of Tudor, Stuart, Valois, and Hapsburg. In the first part of his study Hansen reviews the political and social history of each of the dynasties, and in the second he analyzes the attitudes of various members of the royal families toward the biological facts of life in general and the vicissitudes which many of them encountered in their perilous journeys from conception to death. In each case the emphasis is on dynastic succession and its intricate relationship to the two pertinent biological imperatives: heredity and reproduction, here aptly called (in a nice play on words) the Royal Facts of Life.

In each of the royal families, as Hansen shows, the failure to produce an indisputable hereditary successor led time and again to involuted diplomatic and political machinations, internecine squabbles and wars, and geneological labyrinths abounding in consanguinous Matings. The potent instinct of procreation was almost totally subordinated to the political necessity of an heir to ensure orderly succession. The results were pathetic, especially in the appalling childhood marriages and their devastating effects on body and soul of the partners. Each of the four dynasties, as Hansen makes clear, dealt with the problem of succession in a way which in some measure reflected its national character: the systematic, disciplined approach of the Hapsburgs; the insouciance of the Valois; and the "muddling through" of the Tudors. But in the end biological laws caught up with them. Sometimes sterility altogether prevented the possibility of offspring; more often, interlock- ing unfavorable genes, the results of disease and consanguinous marriages, produced enfeebled or insane offspring. The surprising fact is how well and how long the members of these ruling families stood up to the physical damage caused by medical care based on inadequate knowledge and the ravages of ghastly diseases which we now know only as historical facts.

In reading this book one sometimes has to remind oneself that the subject is, after all, restricted to the Royal Facts of Life. Thus, Hansen omits consideration of the immense cultural accomplishments of the age, the stimulus for which often came from the very victims of these Facts (for example, Rudolph II, 1552-1612).' Moreover, the dynastic family trees might be easier to understand and visualize had they been drawn as pedigrees, using the standard symbols of modern genetics. Finally, to label 16th-century physicians, as Hansen occasionally does, as "ignoramuses" seems unfair. They should be judged by the standards and the state of medical knowledge of their own age, not those of our own.

Since this splendid book was written almost entirely while Hansen was a senior at Dartmouth, it comes as no surprise that upon graduation he received the Class of 1859 Prize for the outstanding thesis in European history. One hopes he will continue his work in this field. Though one hesitates to go as far as Will and Ariel Durant "History is a fragment of biology," they wrote the crossroads at which history and biology intersect is an un- derdeveloped, often undervalued, field of research.

Dr. Hoefnagel is a medical historian andprofessor of maternal and child health at theDartmouth Medical School.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureA Triumphant Failure

October 1980 By Peter Bridges -

Feature

FeaturePornography in Our Time

October 1980 By Mary Ellen Donovan -

Feature

FeatureWhat It Was Was Grid-Graph

October 1980 By John R. Scotford Jr. -

Feature

FeatureA Collection of 'Erotic Capital'

October 1980 By Margaret E. Spicer -

Article

ArticleIntellectual Athlete

October 1980 By Don Rosenthal '81 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1978

October 1980 By JEFF IMMELT

Books

-

Books

BooksShelf Life

Sept/Oct 2004 -

Books

BooksGhost of Quixote

April 1980 By Frank F. Janney -

Books

BooksWAKE ME WHEN IT'S OVER.

October 1955 By HERBERT F. WEST '22 -

Books

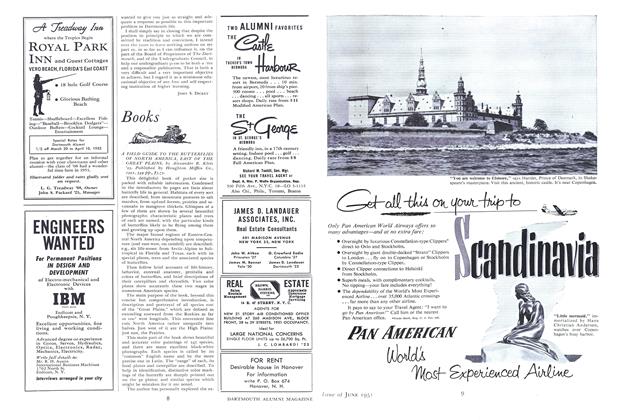

BooksA FIELD GUIDE TO THE BUTTERFLIES OF NORTH AMERICA, EAST OF THE

June 1951 By J. H. Gerould '90 -

Books

BooksGRANITE and SAGEBRUSH,

February 1945 By L. B. Richardson 'OO. -

Books

BooksTHE CHANGES.

JULY 1965 By THOMAS A. CARNICELLI