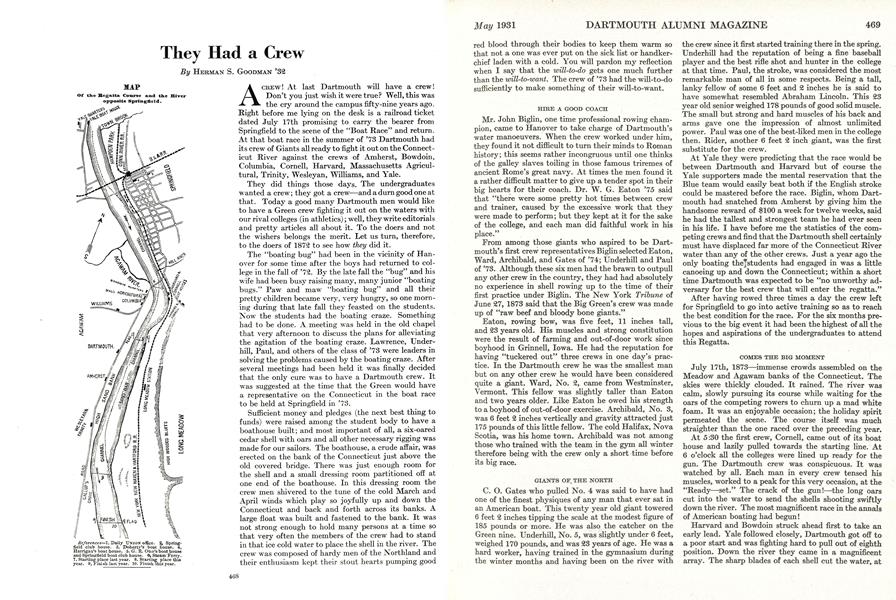

A CREW! At last Dartmouth will have a crew! Don't you just wish it were true? Well, this was the cry around the campus fifty-nine years ago. Right before me lying on the desk is a railroad ticket dated July 17th promising to carry the bearer from Springfield to the scene of the "Boat Race" and return. At that boat race in the summer of '73 Dartmouth had its crew of Giants all ready to fight it out on the Connecticut River against the crews of Amherst, Bowdoin, Columbia, Cornell, Harvard, Massachusetts Agricultural, Trinity, Wesleyan, Williams, and Yale.

They did things those days. The undergraduates wanted a crew; they got a crew—and a durn good one at that. Today a good many Dartmouth men would like to have a Green crew fighting it out on the waters with our rival colleges (in athletics); well, they write editorials and pretty articles all about it. To the doers and not the wishers belongs the merit. Let us turn, therefore, to the doers of 1872 to see how they did it.

The "boating bug" had been in the vicinity of Hanover for some time after the boys had returned to college in the fall of '72. By the late fall the "bug" and his wife had been busy raising many, many junior "boating bugs." Paw and maw "boating bug" and all their pretty children became very, very hungry, so one morning during that late fall they feasted on the students. Now the students had the boating craze. Something had to be done. A meeting was held in the old chapel that very afternoon to discuss the plans for alleviating the agitation of the boating craze. Lawrence, Underhill, Paul, and others of the class of '73 were leaders in solving the problems caused by the boating craze. After several meetings had been held it was finally decided that the only cure was to have a Dartmouth crew. It was suggested at the time that the Green would have a representative on the Connecticut in the boat race to be held at Springfield in '73.

Sufficient money and pledges (the next best thing to funds) were raised among the student body to have a boathouse built; and most important of all, a six-oared cedar shell with oars and all other necessary rigging was made for our sailors. The boathouse, a crude affair, was erected on the bank of the Connecticut just above the old covered bridge. There was just enough room for the shell and a small dressing room partitioned off at one end of the boathouse. In this dressing room the crew men shivered to the tune of the cold March and April winds which play so joyfully up and down the Connecticut and back and forth across its banks. A large float was built and fastened to the bank. It was not strong enough to hold many persons at a time so that very often the members of the crew had to stand in that ice cold water to place the shell in the river. The crew was composed of hardy men of the Northland and their enthusiasm kept their stout hearts pumping good red blood through their bodies to keep them warm so that not a one was ever put on the sick list or handkerchief laden with a cold. You will pardon my reflection when I say that the will-to-do gets one much further than the will-to-want. The crew of '73 had the will-to-do sufficiently to make something of their will-to-want.

HIRE A GOOD COACH

Mr. John Biglin, one time professional rowing champion, came to Hanover to take charge of Dartmouth's water manoeuvers. When the crew worked under him, they found it not difficult to turn their minds to Roman history; this seems rather incongruous until one thinks of the galley slaves toiling in those famous triremes of ancient Rome's great navy. At times the men found it a rather difficult matter to give up a tender spot in their big hearts for their coach. Dr. W. G. Eaton '75 said that "there were some pretty hot times between crew and trainer, caused by the excessive work that they were made to perform; but they kept at it for the sake of the college, and each man did faithful work in his place."

From among those giants who aspired to be Dartmouth's first crew representatives Biglin selected Eaton, Ward, Archibald, and Gates of '74; Underhill and Paul of '73. Although these six men had the brawn to outpull any other crew in the country, they had had absolutely no experience in shell rowing up to the time of their first practice under Biglin. The New York Tribune of June 27, 1873 said that the Big Green's crew was made up of "raw beef and bloody bone giants."

Eaton, rowing bow, was five feet, 11 inches tall, and 23 years old. His muscles and strong constitution were the result of farming and out-of-door work since boyhood in Grinnell, lowa. He had the reputation for having "tuckered out" three crews in one day's practice. In the Dartmouth crew he was the smallest man but on any other crew he would have been considered quite a giant. Ward, No. 2, came from Westminster, Vermont. This fellow was slightly taller than Eaton and two years older. Like Eaton he owed his strength to a boyhood of out-of-door exercise. Archibald, No. 3, was 6 feet 2 inches vertically and gravity attracted just 175 pounds of this little fellow. The cold Halifax, Nova Scotia, was his home town. Archibald was not among those who trained with the team in the gym all winter therefore being with the crew only a short time before its big race.

GIANTS OF. THE NORTH

C. O. Gates who pulled No. 4 was said to have had one of the finest physiques of any man that ever sat in an American boat. This twenty year old giant towered 6 feet 2 inches tipping the scale at the modest figure of 185 pounds or more. He was also the catcher on the Green nine. Underhill, No. 5, was slightly under 6 feet, weighed 170 pounds, and was 23 years of age. He was a hard worker, having trained in the gymnasium during the winter months and having been on the river with the crew since it first started training there in the spring. Underbill had the reputation of being a fine baseball player and the best rifle shot and hunter in the college at that time. Paul, the stroke, was considered the most remarkable man of all in some respects. Being a tall, lanky fellow of some 6 feet and 2 inches he is said to have somewhat resembled Abraham Lincoln. This 23 year old senior weighed 178 pounds of good solid muscle. The small but strong and hard muscles of his back and arms gave one the impression of almost unlimited power. Paul was one of the best-liked men in the college then. Rider, another 6 feet 2 inch giant, was the first substitute for the crew.

At Yale they were predicting that the race would be between Dartmouth and Harvard but of course the Yale supporters made the mental reservation that the Blue team would easily beat both if the English stroke could be mastered before the race. Biglin, whom Dartmouth had snatched from Amherst by giving him the handsome reward of $100 a week for twelve weeks, said he had the tallest and strongest team he had ever seen in his life. I have before me the statistics of the competing crews and find that the Dartmouth shell certainly must have displaced far more of the Connecticut River water than any of the other crews. Just a year ago the only boating the students had engaged in was a little canoeing up and down the Connecticut; within a short time Dartmouth was expected to be "no unworthy adversary for the best crew that will enter the regatta."

After having rowed three times a day the crew left for Springfield to go into active training so as to reach the best condition for the race. For the six months previous to the big event it had been the highest of all the hopes and aspirations of the undergraduates to attend this Regatta.

COMES THE BIG MOMENT

July 17th, 1873—immense crowds assembled on the Meadow and Agawam banks of the Connecticut. The skies were thickly clouded. It rained. The river was calm, slowly pursuing its course while waiting for the oars of the competing rowers to churn up a mad white foam. It was an enjoyable occasion; the holiday spirit permeated the scene. The course itself was much straighter than the one raced over the preceding year.

At 5:30 the first crew, Cornell, came out of its boat house and lazily pulled towards the starting line. At 6 o'clock all the colleges were lined up ready for the gun. The Dartmouth crew was conspicuous. It was watched by all. Each man in every crew tensed his muscles, worked to a peak for this very occasion, at the "Ready—set." The crack of the gun!—the long oars cut into the water to send the shells shooting swiftly down the river. The most magnificent race in the annals of American boating had begun!

Harvard and Bowdoin struck ahead first to take an early lead. Yale followed closely, Dartmouth got off to a poor start and was fighting hard to pull out of eighth position. Down the river they came in a magnificent array. The sharp blades of each shell cut the water, at first sweeping out, then in close to the sides of the frail crafts, to be raised out of the water and poised for the briefest interval before being plunged into the river once again. It was the rhythm of muscle and sinew. The boys wearing the "green caps" were making up for an early misfortune—No. 4 was unprepared at the start and immediately afterward Underhill had slipped the button of his oar beyond the rowlock, not getting control of the oar again for nearly twenty strokes. Yes, the Green shell was making time now. Harvard struggled heroically hugging the eastern shore. Wesleyan seemed to make a spurt for the finish. Yale showed her steady English stroke to make obvious gains. Dartmouth increased its count—passed number seven— overtook number six—was alongside number five— passed five. Excitement—shouts—wild cries of "Pull for your lives." Dartmouth was trying to overtake Harvard while Yale crossed the line first. The race was over. The Indians finished fourth. Everyone was satisfied with the valiant fighting of the Green.

FINISH OF THE 1873 INTERCOLLEGIATE REGATTA CONNECTICUT RIVER NEAR SPRINGFIELD

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Class Notes

Class NotesCLASS OF 1930

May 1931 By Albert I. Dickerson -

Class Notes

Class NotesCLASS OF 1910

May 1931 By "Hap" Hinman -

Lettter from the Editor

Lettter from the EditorEditorial Comment

May 1931 -

Article

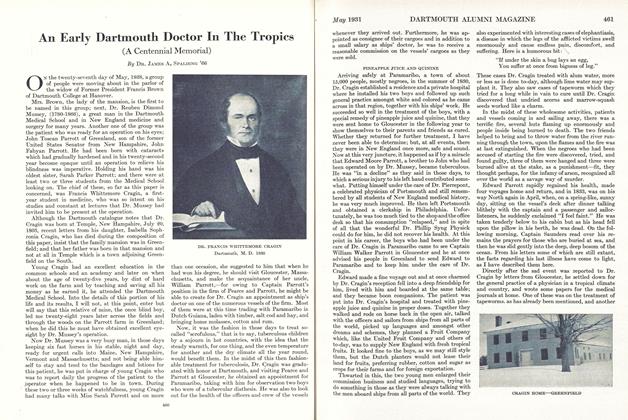

Article(A Centennial Memorial)

May 1931 By Dr. James A. Spalding '66 -

Class Notes

Class NotesCLASS OF 1929

May 1931 By Frederick W. Andres -

Class Notes

Class NotesCLASS OF 1924

May 1931 By C. Jerry Spaulding

Article

-

Article

ArticlePALMER CAPTAINS TRACK TEAM

June, 1909 -

Article

ArticleComing Secretaries' Meeting

January, 1911 -

Article

Article1960 Alumni Fund

January 1960 -

Article

ArticleMaking the Grade

NOVEMBER 1996 -

Article

ArticleARTHUR FAIRBANKS '86

March 1944 By DR. FREDERIC P. LORD '98 -

Article

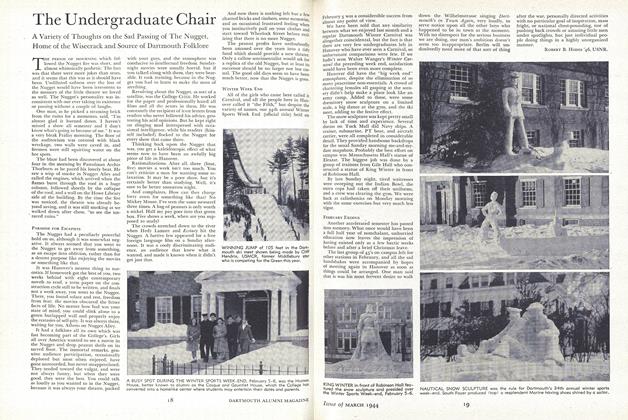

ArticleFEBRUARY EXODUS

March 1944 By Robert B. Hodes '46, USNR