ON the twenty-seventh day of May, 1828, a group of people were moving about in the parlor of the widow of Former President Francis Brown of Dartmouth College at Hanover.

Mrs. Brown, the lady of the mansion, is the first to be named in this group; next, Dr. Reuben Dimond Mussey, (1780-1866), a great man in the Dartmouth Medical School and in New England medicine and surgery for many years. Another one of the group was the patient who was ready for an operation on his eyes; John Toscan Parrott of Greenland, son of the former United States Senator from New Hampshire, John Fabyan Parrott. He had been born with cataracts which had gradually hardened and in his twenty-second year become opaque until an operation to relieve his blindness was imperative. Holding his hand was his oldest sister, Sarah Parker Parrott; and there were at least two or three students from the Medical School looking on. The chief of these, so far as this paper is concerned, was Francis Whittemore Cragin, a firstyear student in medicine, who was so intent on his studies and constant at lectures that Dr. Mussey had invited him to be present at the operation.

Although the Dartmouth catalogue notes that Dr. Cragin was born at Temple, New Hampshire, July 20, 1803, recent letters from his daughter, Isabella Sophronia Cragin, who has died during the composition of this paper, insist that the family mansion was in Greenfield; and that her father was born in that mansion and not at all in Temple which is a town adjoining Greenfield on the South.

Young Cragin had an excellent education in the common schools and an academy and later on when about the age of twenty-five years, by dint of hard work on the farm and by teaching and saving all his money as he earned it, he attended the Dartmouth Medical School. Into the details of this portion of his life and its results, I will not, at this point, enter but will say that this relative of mine, the once blind boy, led me twenty-eight years later across the fields and through the woods on the Parrott farm in Greenland; when he did this he must have obtained excellent eyesight by Dr. Mussey's operation.

Now Dr. Mussey was a very busy man, in those days keeping six fast horses in his stable, night and day, ready for urgent calls into Maine, New Hampshire, Vermont and Massachusetts; and not being able himself to stay and tend to the bandages and lotions for this patient, he was put in charge of young Cragin who was to report daily the progress of the patient to the operator when he happened to be in town. During these two or three weeks of watchfulness, young Cragin had many talks with Miss Sarah Parrott and on more than one occasion, she suggested to him that when he had won his degree, he should visit Gloucester, Massachusetts, and make the acquaintance of her uncle, William Parrott,—for owing to Captain Parrott's position in the firm of Pearce and Parrott, he might be able to create for Dr. Cragin an appointment as ship's doctor on one of the numerous vessels of the firm. Most of them were at this time trading with Paramaribo in Dutch Guiana, laden with timber, salt cod and hay, and bringing home molasses, cotton and rum.

Now, it was the fashion in those days to treat socalled "scrofulous," that is to say, tuberculous children by a sojourn in hot countries, with the idea that the steady warmth, for one thing, and the even temperature for another and the dry climate all the year round, would benefit them. In the midst of this then fashionable treatment for tuberculosis, Dr. Cragin was graduated with honor at Dartmouth, and visiting Pearce and Parrott at Gloucester, he obtained an appointment for Paramaribo, taking with him for observation two boys who were of a tubercular diathesis. He was also to look out for the health of the officers and crew of the vessels whenever they arrived out. Furthermore, he was appointed as consignee of their cargoes and in addition to a small salary as ships' doctor, he was to receive a reasonable commission on the vessels' cargoes as they were sold.

PINEAPPLE JUICE AND QUININE

Arriving safely at Paramaribo, a town of about 15,000 people, mostly negroes, in the summer of 1830, Dr. Cragin established a residence and a private hospital where he installed his two boys and followed up such general practice amongst white and colored as he came across in that region, together with his ships' work. He succeeded so well in the treatment of the boys, with a special remedy of pineapple juice and quinine, that they were sent home to Gloucester in the following year to show themselves to their parents and friends as cured. Whether they returned for further treatment, I have never been able to determine; but, at all events, there they were in New England once more, safe and sound. Now at this very juncture, it happened as if by a miracle that Edward Moore Parrott, a brother to John who had been operated on by Dr. Mussey, became tuberculous. He was "in a decline" as they said in those days, to which a serious injury to his left hand contributed some- what. Putting himself under the care of Dr. Pierrepont, a celebrated physician of Portsmouth and still remem- bered by all students of New England medical history, he was very much improved. He then left Portsmouth and obtained a clerkship in Philadelphia. Unfor- tunately, he was too much tied to the shop and the office desk so that his consumption "relapsed," and in spite of all that the wonderful Dr. Phillip Syng Physick could do for him, he did not recover his health. At this point in his career, the boys who had been under the care of Dr. Cragin in Paramaribo came to see Captain William Walker Parrott in Gloucester and he at once advised his people in Greenland to send Edward to Paramaribo and to keep him under the care of Dr. Cragin.

Edward made a fine voyage out and at once charmed by Dr. Cragin's reception fell into a deep friendship for him, lived with him and boarded at the same table; and they became boon companions. The patient was put into Dr. Cragin's hospital and treated with pineapple juice and quinine in proper doses. Together they walked and rode on horse back in the open air, talked with the officers and sailors from ships from all parts of the world, picked up languages and amongst other dreams and schemes, they planned a Fruit Company which, like the United Fruit Company and others of to-day, was to supply New England with fresh tropical fruits. It looked fine to the boys, as we may still style them, but the Dutch planters would not lease their land for fruits, preferring rubber, cotton and sugar as crops for their farms and for foreign exportation.

Thwarted in this, the two young men enlarged their commission business and studied languages, trying to do something in those as they were always talking with the men aboard ships from all parts of the world. They also experimented with interesting cases of elephantiasis, a disease in which the legs of the afflicted victims swell enormously and cause endless pain, discomfort, and suffering. Here is a humorous bit: "If under the skin a bug lays an egg, You suffer at once from bigness of leg." These cases Dr. Cragin treated with alum water, more or less as is done to-day, although lime water may supplant it. They also saw cases of tapeworm which they tried for a long while in vain to cure until Dr. Cragin discovered that undried acorns and marrow-squash seeds worked like a charm.

In the midst of these wholesome activities, patients and vessels coming in and sailing away, there was a terrific fire, several huts flaming up enormously and people inside being burned to death. The two friends helped to bring and to throw water from the river running through the town, upon the flames and the fire was at last extinguished. When the negroes who had been accused of starting the fire were discovered, tried, and found guilty, three of them were hanged and three were burned alive at the stake, as a punishment—fit, they thought perhaps, for the infamy of arson, recognized all over the world as a savage way of murder.

Edward Parrott rapidly regained his health, made four voyages home and return, and in 1833, was on his way North again in April, when, on a spring-like, sunny day, sitting on the vessel's deck after dinner talking blithely with the captain and a passenger and sailorlisteners, he suddenly exclaimed "I feel faint." He was taken tenderly below to his cabin but as his head fell upon the pillow in his berth, he was dead. On the following morning, Captain Saunders read over his remains the prayers for those who are buried at sea, and then he was slid gently into the deep, deep bosom of the ocean. From his letters some of which are still extant, the facts regarding his last illness have come to light, as I have described them here.

Directly after the sad event was reported to Dr. Cragin by letters from Gloucester, he settled down for the general practice of a physician in a tropical climate and country, and wrote some papers for the medical journals at home. One of these was on the treatment of tapeworms, as has already been mentioned, and another on hemorrhages from the lungs. Other papers were contributed to medical journals in the United States, but so far, only these two have been discovered.

ADVENTURES OF DR. CRAGIN

From 1833 until 1846, Dr. Cragin continued his labors as a physician using two horses for distant patients and, when called upon by American sea captains in port, adjusted differences between them and the Dutch Government. In this way he gradually became acquainted with the duties of a Consul. Then there was the affair of the Brig-Sarah of Prospect, Maine, which drifted into Paramaribo, one afternoon, with the captain, mate and crew all dead from yellow fever. In this case he was active in helping the consignees of the vessel by the use of the authority of the United States Government and arranging the disposition of the cargo and of the money on board, more than $1,000 in specie and bills. There was also an Austrian vessel, the "Venezie," which the Dutch authorities claimed to have been deserted by its crew who had all died on shore of yellow fever. Dr. Cragin, acting as intermediator between the Dutch and Austrian Governments, settled the affair with honor to all concerned.

Finding that he was becoming more and more interested in Consular work, Dr. Cragin applied to be nominated United States Consul at Paramaribo which was granted June 8, 1846. In the following year, he came home and met his old friends in Boston and elsewhere, went to Greenfield, became engaged to Miss Martha Isabella Fowler of Stockbridge, Massachusetts and leaving her, returned to his labors as Consul and physician. His consular duties are easy to understand, and his medical business was to look out for injuries on plantations, cuts with tools, scaldings from boiling sugar, ordinary diseases of tropical countries, bilious fevers, and one or two epidemics of yellow fever which started again in Demerara and extended into Paramaribo. Then there were a good many ordinary ships' diseases, and injuries; but into this part of his life we need not go too closely in a paper not intended for a medical society. Enough to say, that, in a general way, he was kept busy all of the time and finally made other short voyages home and married Miss Fowler, leaving her in Greenfield.

When and where his parents died (Polly and Molly as they were generally known in passing up and down the main street of the village) I have not, so far, discovered.

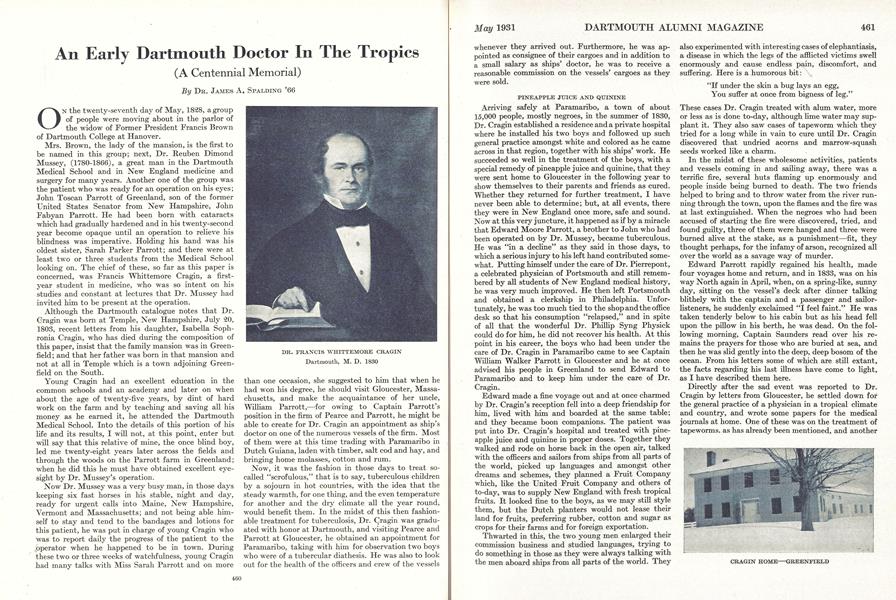

Now it happened in 1851, that there was an epidemic of yellow fever raging in Surinam with great violence; many people died and in the midst of it, Mrs. Cragin who had been sent for from home, arrived with her daughter, Isabella, who had been born in 1850; and within a week, the young bride was dead from yellow fever and she remains buried in Paramaribo. The little girl, Isabella Sophronia Cragin, "my darling," as Dr. Cragin always called her, was taken home in the care of a negro woman of whom she had become very fond and much attached to in that short vacation in the tropics. Isabella spent part of her life in Greenfield, later in Massachusetts, in obtaining an education and ultimately a degree of A.M. in a Western college. She wrote delightful letters to me about her people, sent me a wonderful portrait of her father which we see above and only in last January when I was expecting to see her soon, she departed from the scenes of her labors, leaving amongst other remembrances a most delightful book: "Our Insect Friends and Foes."

LETTER TO WEBSTER

After the death of his wife, Dr. Cragin, a griefstricken man, retired from practice, gradually, and devoted the rest of the following years to consular duties at Paramaribo. Finally his health gave way after thirty years of tropical temperature and climate and in 1857, he handed in his resignation to the State Department. I had forgotten to say that two or three of his letters from Paramaribo to the United States State Department at Washington, directed to our great Daniel Webster, as Secretary of State, have been unearthed by me, and serve as guides for the history of Dr. Cragin, another Dartmouth graduate. We may sum up the last eleven years of Cragin's consulate as revealing an active and busy man, and from dispatches of his that have come down to us we note that they are wellwritten documents and pleasant to read,—for they show him to be an educated man and a master of his business.

Arriving home in the fall of 1857, he married as a second wife, Miss Mary Anne Leßosquet, daughter of the minister at Greenfield. He then began to build over the family mansion with a view of establishing a medical practice in the town; but in the following winter he developed symptoms of a nervous breakdown, due, as the attending physicians held, to the hardening of the blood vessels of his brain. In spite of all they could do, he gradually failed and left his wife and little daughter, Isabella, July 26, 1858. To his wife was born a posthumous son named after his father.

For many years the catalogues of Dartmouth College failed to give a clue to our Francis Whittemore Cragin but now I am very glad by the discovery of old letters on my mother's side, the Parrotts, to have thrown light on Cragin's very interesting, remarkable, and, in fact, unique career. Dartmouth gave him a good education in medicine and he honored the old College which he loved so dearly,—by revealing wonderful skill in medicine, and in the foreign affairs of our Government.

DR. FRANCIS WHITTEMORE CRAGIN Dartmouth, M. D. 1830

CRAGIN HOME—GREENFIELD

OLD PINE N. H. MEDICAL, COLLEGE OBSERVATORY Hanover, N. H.

MEDICAL COLLEGE, HANOVER

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Class Notes

Class NotesCLASS OF 1930

May 1931 By Albert I. Dickerson -

Class Notes

Class NotesCLASS OF 1910

May 1931 By "Hap" Hinman -

Lettter from the Editor

Lettter from the EditorEditorial Comment

May 1931 -

Class Notes

Class NotesCLASS OF 1929

May 1931 By Frederick W. Andres -

Class Notes

Class NotesCLASS OF 1924

May 1931 By C. Jerry Spaulding -

Article

ArticleThey Had a Crew

May 1931 By Herman S. Goodman '32

Dr. James A. Spalding '66

Article

-

Article

ArticleSECONDARY SCHOOL PLANNED FOR HANOVER

May 1919 -

Article

ArticleWhat Answers Can Thinking Dartmouth Men Give to the Atomic Threat of Brutal Nihilism?

May 1946 -

Article

ArticleGreat Issues Speakers

January 1950 -

Article

ArticleTap Secret

June 1989 -

Article

ArticleArmy Unit Added

February 1951 By C. E. W. -

Article

ArticleThe 1949 Valedictory

July 1949 By RAYMOND J. RASENBERGER '49