Part III Turns (Continued) Practical Use of Turns for Control

Foreword by Mr. McCrillis

IN the foreword to the first article of this series, which told of Coach Schniebs and his work, space did not permit including some things which should be told in order to give a true picture of the development 'of skiing at Dartmouth.

Coach Schniebs—or any other coach would never have come to Dartmouth if generations of Dartmouth men had not been building the Outing Club bigger and stronger for over twenty years, and if the sport of skiing had not been growing steadily more popular due to the hundreds—yes, thousands of Dartmouth men who have been ski enthusiasts for over two score years, and were it not for the continuing guidance and leadership of such members of the faculty as Prof. C. A. Proctor and Prof. J. W. Goldthwait, who are themselves enthusiastic and proficient skiers.

To show conditions a dozen years ago and to show the vision of these members of the faculty, I quote from an article written by Prof. Goldthwait in an article in "Dartmouth The Winter College" published in 1920.

"This season it is probable that between one hundred and three hundred freshmen strap on skis for the first time. What are they doing during these first weeks of snow—the critical weeks of their skiing experience? Are they to pick up the new sport as freshmen in 1910 picked it up, boldly and enthusiastically to be sure, but without coaching? Friendship or chance contact with an upperclass ski expert may show many of these new skiers the difference between the graceful and adroit performance of the practiced ski-runner and the awkward, uncontrolled orgy of the wildman on skis, swooping downhill with feet wide apart, crouching with clenched fists and outstretched arms, or brandishing a pair of iron pointed spears. Lacking this advantage the beginner is liable to feel early disappointment in the sport which may grow into fixed skepticism either as regards the value of this sport itself or as regards his own use for it. A sprained ankle or a bruised knee at this stage may mark the end of his interest in skiing. If, on the other hand, his interest continues, the lack of proper coaching at the outset is almost sure to have given him bad habits of position and balance and the use of sticks which must all be unlearned, before he can run speedily, easily, and with good control. He may in time become a fair ski-runner; but meanwhile his friends will be doing S turns around him. Both he and they will tell you that skiing is great sport; but which sort of skier is the better judge of the fun he is having?

"Here, then, is the problem, to make it possible for every new Dartmouth man who takes to skis to get sound, helpful instruction in ski-running at the start, to teach him to see that the habits he acquires during the first, second, and third weeks of skiing are good, so that they fit him to make rapid progress in acquiring all the tricks of the profession. At this stage instruction is simple to give, and easily followed. . . .

"The desirability of some such organized coaching as this has been talked of for several years. Present conditions make it all the more advisable. Compulsory recreation would gain in interest, and the favorite winter sport would be greatly encouraged during the months when the gridiron, the baseball diamond and the tennis courts are buried in snow, if supervised skiing were added to the program."

The freshman is no longer "the wildman on skis, swooping downhill with feet wide apart brandishing a pair of iron pointed spears." That he is not, he should be thankful, not only to his present coaches, but also to the army of men, former undergraduates, former coaches,* and members of the faculty, who have been building up the sport in Hanover for over two decades.

As the sport has grown in the past twenty years, so may it continue to do in the next!

SKATING

SKATING rhythmically on skis is not only an interesting and enjoyable variation from the other forms of skiing used for descending gentle slopes and on the level, but it also is a very practical thing to learn. Nothing teaches balance in just the same way that skating does. The man who can skate well also finds this a great assistance in helping him "step" around corners in trail running. Three essentials for skating are: bend forward knee as much as possible, keeping heel on ski; swing the body over the forward ski; take long, slow, rhythmical strokes.

PURE CHRISTIANIA

The pure christiania is a turn which can be made very quickly and is much used for "linked" turns (a series of turns, first to one side, then to the other). It may be used on any slope, at any speed, and on any sort of snow (except heavy breakable crust). As a man comes down a steep mountain at high speed, doing a series of pure christianias with the steadiness and grace so characteristic of the turn, a very noticeable thing is the rhythm of the "down-up-down" motion of each separate swing, as he dips into a crouch, rises, and crouches as he swings again.

It is very important that skis be held as nearly flat as possible during the early part of a turn, and they are held as nearly parallel as possible. Both skis are weighted and unweighted equally and at the same time by the down-up-down motion of the body. This characteristic down-up-down motion is more pronounced at low speed, and in deep and heavy snow. At high speed and in snow which offers less resistance to the turn this motion is less, and may be very slight. Near the end of the turn the skier leans in somewhat, and the downhill or outer ski may be pushed downhill to give a better sideward balance.

The importance of learning the rhythm of the downup-down motion cannot be overemphasized.

JERKED CHRISTIANIA

When the pure christiania just described is made very quickly and sharply it is sometimes called a "jerked christiania." The down-up-down motion is usually so abrupt it looks something like a little jump.

When a christiania is made very quickly it is often hard to tell whether it is a pure, jerked, or stem "christie." What a turn may be called is of little concern. Whether it works is what counts.

STEM CHRISTIANLA.

The most used turn of the modern style of skiing is the stem christiania. It is used on all sorts of slopes, at all speeds, and on all snow (except very heavy breakable crust). It is a combination of the single stem turn, pure christiania, and open christiania. With this turn the skier can easily turn more than ninety degrees. The first motion is to stem with the outside ski as in a single stem turn. The duration of the stemming action depends on various conditions, and may sometimes be so brief as to be hardly discernible. Then the body is raised and swung as in the pure christiania. Then as the body goes down as in the pure christiania the ski points are separated as in the open christiania, and the turn is continued in this position as long as desired.

GELANDESPRUNG OR OBSTACLE-JUMP

There are many variations of the gelandesprung, which is used for jumping over rocks, ditches, drifts, fences, or other obstructions. This may be done with or without poles, and does not require a take-off. Although the obstacle-jump is used little in practical skiing in comparison with the turns which have been described, it is useful on occasion, and has a fascination which makes skiers want to master it.

A gelandesprung with the aid of the poles is described in the picture series. Many things learned in the jump turn apply here: start from a low crouch; keep knees, ankles, and skis together until just before landing; keep tips of skis out of snow, so as not to trip; bring knees as near chest as possible; absorb shock of landing by bending knees.

The poles should be carried at the side and pointing backward until the skier is ready to insert them. Assistance of the poles should not be used at too high speed. More than one expert skier has been seriously injured by trying to use his poles when going too fast.

JUMPING FENCE

The accompanying picture shows the skier jumping a barbed wire fence. He stood close to the fence, skis parallel to the fence, left hand on fence post, left pole hanging free at the farther side of the fence, with hand firmly gripping right pole. Then, after quickly going into a low crouch position, he suddenly straightened his body and turned it to the left. He is now seen drawing his knees toward his chest as he swings the skis over the wire. He will land with skis parallel to, and near the fence, but pointed in the opposite direction from that when the jump was started.

VI. PRACTICAL USE OF TURNS FOR CONTROL

COMBINED TURNS

ONE of the fascinating things about skiing is that with the ever-changing conditions of snow, slope, speed, and the twisting of the trail, the skier is constantly called on to use his judgment as to what is the best thing for HIM to do under each set of conditions.

The turns we have described give the skier the fundamentals of control on which he can build a great number of variations and combinations of turns. When a skier has mastered the fundamental turns so that their execution is automatic he uses not only these turns in ski running, but he also combines them in many ways, and he combines them so naturally and automatically that after a series of successful swings he may not be able to analyze just what he has done. He just "makes the turns" as the football player plays his game without stopping to plan or analyze every movement of limb or body.

One of the most common of combined turns is done by starting to stem and finishing the swing as a telemark. This is sometimes called the "stem-telemark."

The stem-christiania, a most important combination turn, has already been described with the aid of pictures.

We will give one more example, a turn as recorded by the motion picture camera. The skier started an open christiania to the right; then stemmed with his right foot, swung into a telemark to the left, and finished the turn to the left by suddenly drawing his left foot forward and ending the turn as a christiania.

Combined turns are very useful and the skier who can execute the fundamental turns we have described will automatically make the combined turns, doing whatever serves him the best for the moment under the existing conditions of speed, snow, and slope.

Remember this. The test of a turn is not "What does the book say," but rather "How did the turn work."

DOWN-MOUNTAIN RACING

To demonstrate the application of the modern ski technique in down-mountain racing we show some stills from a motion picture of the Dartmouth Outing Club race on Mt. Moosilauke where the racers drop about 2900 feet in 2.8 miles of winding trail, making dozens of sharp turns at very high speed.

RIDING THE DRIFTS

This picture shows how the skier uses his knees as shock absorbers. As his skis ride over the crest of one of a series of deep drifts—which are like waves across the trail—he brings his knees nearly to his chest. As the skis slide down the lower side of the drift he will straighten his knees somewhat, again bending them as the skis soon start up the next drift. Note correct position of the poles.

STEM CHRISTIANIA

Note the low crouch used by this expert runner as he rounds one part of a double turn at very high speed. This turn was started in the single stem position. The picture shows the skier with skis parallel, after he has gone into the pure christiania position. To prevent being thrown outward by his momentum the skier leans inward as he rounds the corner. The outside ski is thrust outward to help give him good sideward balance. The next moment the skier will be in the open christiania position with his weight on the inside ski.

CHRISTIANIA BY PROCTOR

This series of three pictures shows Charley Proctor, one of the best down-mountain racers in the United States, and a member of the 1928 U. S. Olympic Team, doing a beautiful stem christiania.

As determined from the motion picture, the time between the first and second pictures is a second and a half. The time between the second and third pictures is but an eighth of a second.

RUNNING VERT STEEP SLOPES

The picture of Tuckerman's Ravine on Mt. Washington shows an example of a very steep open slope which can be descended without falling by keeping skis always under control. The route of descent is indicated by a line in the picture. A fall near the top means that the skier rolls or slides hundreds of feet to the bottom of the headwall.

Most skiers who successfully negotiate this type of descent start a majority of the turns on the steepest parts as stem-christianias. The turns may be finished as some form of christiania, or often as a lifted stem.

The thrills of successfully skiing on such slopes or of making a creditable descent of a mountain are rich compensation for what work and time it may have cost to gain mastery of the turns to gain control.

SKATING

PURE CHRISTIANIA

STEM CHRISTIANIA

OBSTACLE JUMP (GELANDESPRUNG)

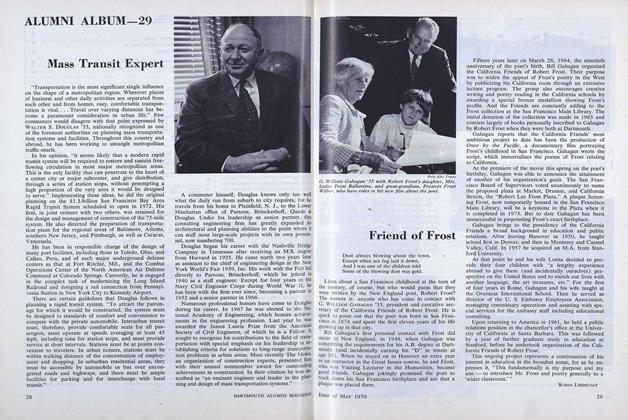

JOHN W. McCRILLIS 'l9 Co-author with Coach Otto Schniebs of the skiing articles of which this month's is the third and last installment

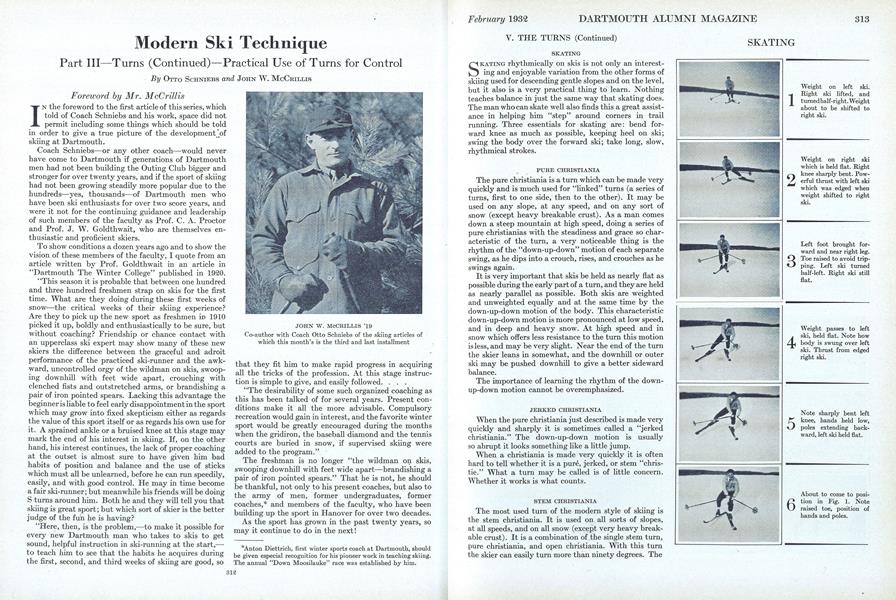

Weight on left ski. 1 Right ski lifted, and turnedhalf-right. Weight about to be shifted to right ski.

Weight on right ski which is held flat. Right 2 knee sharply bent. Pow- erful thrust with left ski which was edged when weight shifted to right ski.

Left foot brought for- ward and near right leg. 3 Toe raised to avoid trip- ping. Left ski turned half-left. Right ski still flat.

Weight passes to left 4 ski, held flat. Note how body is swung over left ski. Thrust from edged right ski.

Note sharply bent left 5 knee, hands held low, poles extending back- ward, left ski held flat.

About to come to posi- 6tion in Fig. 1. Note raised toe, position of hands and poles.

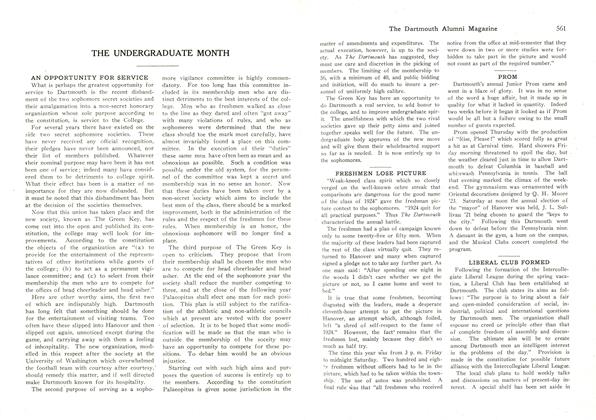

Skier has gone DOWN linto a low crouch for turn to left. Skis parallel, flat, and slightly sepa- rated.

Skier starting UP. Body 2 is beginning to turn to- ward left. Right shoulder and right pole are brought forward.

Body still going UP, and 3 swinging to left. Right shoulder and pole are farther forward. Skis start to turn.

4 As body starts DOWN pressure on heels helps force rear of skis around.

Skier goes DOWN more as he continues turning 5 and leans in, toward slope. Note position of hands, and how they have been swung to left to help the turn.

Typical position as turn is completed. Note how 6 hands almost touch snow. Right ski is being pushed downhill to give good sideward balance.

Skier is DOWN in me- Idium crouch position. Starting to stem with left foot. Both heels flat on skis throughout turn.

Body is starting UP. 2 Stemming with left foot. Left shoulder being swung around. Body leans forward. Skis flat.

Skier is now UP and is 3 in same position that he assumes when UP in pure christiania. Body swing- ing to right.

Skier has started DOWN as he swings his body to 4 the right and leans in. Pressure on the heels faces rear of skis down- hill. Skis weighted equally.

Skier has gone DOWN 5 as he leans in and for- ward. Weight is on both skis, which are slightly edged.

Finishing in open chris- tiania position. Inside ski advanced, turned, 6 edged, and weighted. The skier looks at place where he will start next turn to the right, which he will do by stemming his right ski.

JUMPING FENCE

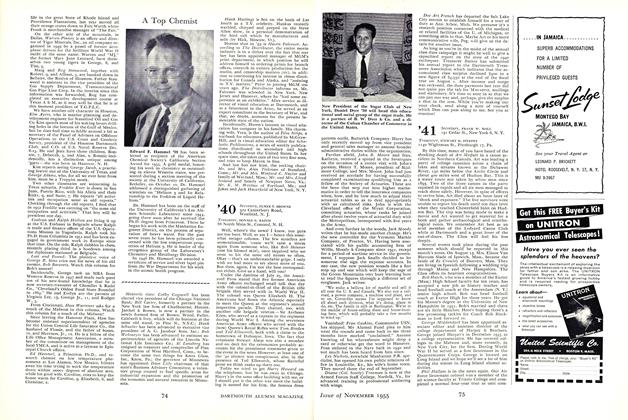

Poles have just been 1 brought forward. Note typical low crouch posi- tion. Knees and ankles touching.

Skier has straightened for fraction of a second 2 to determine most favor- able place to insert poles. Knees and ankles touch- ing.

Low crouch again. Poles 3 inserted close to and in a line with place where front ends of skis will leave snow.

Skier "pole vaults" with 4 both poles. Arms straight, as if elongation of poles. Knees drawn up to chest.

When feet first touch ground knees are straightened somewhat. Skis are separated 5 slightly to avoid injury to feet and ankles. One foot slightly advanced to help forward balance. Poles again point back- ward.

Knees bent more to les- sen shock of landing. The skier will proba- 6bly go into a deeper crouch to absorb shock even more before resum- ing desired running posi- tion.

CHRIS TI AN IA BY PROCTOR

1 Double stem position. As the snow is packed hard outside ski is edged some- what.

2 Flying snow hides left ski which is par- allel to right ski. Both skis are weighted.

3 Right knee bent as right ski is weighted in open christiania position.

RIDING THE DRIFTS

STEM CHRISTIANIA

TUCKERMAN'S RAVINE Showing Route of Precipitous Descent

*Anton Diettrich, first winter sports coach at Dartmouth, should be given especial recognition for his pioneer work in teaching skiing. The annual "Down Moosilauke" race was established by him.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Article

ArticleOld Timers

February 1932 By Professor Emeritus Edwin J. Bartldlett -

Class Notes

Class NotesCLASS OF 1926

February 1932 By J. Branton Wallace -

Class Notes

Class NotesCLASS OF 1905

February 1932 By Arthur E. McClary -

Lettter from the Editor

Lettter from the EditorWith Other Editors

February 1932 -

Class Notes

Class NotesCLASS OF 1910

February 1932 By Harold P. Hinman -

Class Notes

Class NotesCLASS OF 1929

February 1932 By Frederick William Andres