ON the reflection which naturally comes with advancing years I am glad that I first knew this village when it could properly be called "Old Hanover." I came in 1868, and there was little change when I returned in 1879. In the time between graduation and return no building had been erected for the College, and I cannot recall any new stores or dwellings and I do recall nearly all the old ones in their places. I had come from Chicago where all things were in rapid motion, and the calm, some would say stagnation, prevailing here gave me the feeling, which has grown as I have looked back, that I had retired into the 18th century. Of course there had been startling events since the year 1800. Reed, Thornton and Wentworth Halls had been built for the College; a railroad in Vermont had reduced the dominating stage coaches to mere depot busses; Morse had invented a telegraph; a grand bridge had been built across the Connecticut and ceremonially dedicated; Listerism was beginning to revolutionize surgery. But Hanover had neither a water supply nor sewers; heating and lighting were as of yore; plumbing was an adventure; one or two had tried it, but not the Dartmouth Hotel; instead of the steam fire engine, a roaring and thrilling monster of the home town, there was the hardworking heartbreaking manpowered tub; and if one yelled "fire" long enough and loud enough in the night hardy citizens could be gathered to drag it from its hiding place and produce something like artificial respiration till relieved by the next relay of reluctant comers. And when the water from the nearest street tank was exhausted every one felt at liberty to stop work and watch the fire. Fortunately the cigarette was little known in these remote parts and scholarship men were not allowed to smoke anyway. An unnameable odor floated in the autumn mist over a village of open drains and out-houses. And it was one of the inscrutable laws of nature that there should be an epidemic of typhoid fever every fall with only a few fatal cases.

The college faculty were earnest hard-working men feeling strongly the necessity of setting a good example. But they were deep in the mud of precedent and of college lege poverty. Improvements were unusual and cost money, and any one too progressive was liable to be called elsewhere. The students were from less widely separated regions, and though they were the reason for the village they did not influence it greatly. Even then there were bitter complaints of a curriculum so largely classical. For there never was complete escape from Latin or Greek. It seemed sometimes as though scientific studies were looked on as interlopers which interfered with true learning.

In the period to which I refer nearly half way back to the 18th century Hanover was an isolated community. The easy come-and-go of the present was unknown, almost unimaginable. There is no shut-in part of the year now. And it is a rare day in the busy season when someone is not here from the suburbs Boston, Oxford or Jerusalem bringing wisdom or entertainment or competition, and when some "team" is not abroad in the country asking no odds from any one. In those days it was usually necessary to furnish information in order to get a trunk checked to Hanover from outside of New England. Students had three cuts each term, but they generally stayed in their places from the beginning to the end. A few made wild expeditions to Lebanon. Some of the more adventurous and affluent of the inhabitants made well-considered trips to Boston or even New York. The traveling salesman came, but tarried not long. He did not like the hotel.

To this homely life I attribute largely the peculiarities of the people; for they were a little queer. Or perhaps I should say the percentage of queer ones was large. Quaintness, eccentricity, which to a large degree are polished off by intercourse with strangers, novel experiences, and only slightly disguised ridicule, flourished along the street. The people were natural, or at any rate took no pains not to be natural. Accordingly "characters" were numerous, and it is to be regretted that some gifted person could not embalm them in literature when they were fresh. I am glad that I knew some of them myself and knew about many others.

LIFE IN THE HOTEL

I suppose the Frarys, in that almost colonial tavern, come first—so many people met them. I have given them attention elsewhere, but they made permanent and salient memories in the minds of those who knew them. Ask any survivor. There are yet many who ate at their table; but few "regular boarders" survive. I had my first meal there sixty-three years ago, and eleven years later became a regular boarder for two years. I can see yet that wonderfully unadorned dining room shut in for rough weather by movable partitions. With these removed Commencement dinner was held there. At its south end stood Mrs. Frary with one eye watching Horace slice the meat and with the other following Lottie as she delivered the goods. Mrs. Frary could not really do this as her eyes were normal, but it seemed so. With her voice she could hit the target in any part of the room; so she did not need to travel. But occasionally when discussion arose between Lottie and some untrained transient the flapping of her slipper-shod feet gave notice that she was coming to see about it. She usually settled the controversy in favor of the house. The regular boarders included for four or five years the president of the College for the simple reason that there was no available house in the village, and the resources of the College did not at that time run to anything so extravagant as building him one. Impossible! Yes, and at that time the radio, the automobile, the aeroplane, and moving pictures were impossible. Of the regulars I can recall only four,—Squire Duncan, whose deceased wife had been a sister of Rufus Choate's wife, easily autocrat of the breakfast table if he arrived in time, and of the other tables, so unusual a conversationalist or rather monologist that everyone was glad to stop and listen, occasionally over emphatic; Madam Haddock who with her husband had once represented our country in foreign lands, now so handicapped by an ear trumpet that she was likely to start a discourse upon the overcooking of her egg even while the Squire was giving his views upon reconstruction or The Youth of Today; N. A. McClary, who kept the College Bookstore, graduated in the class of '84 and is to-day one of my friends among those faraway classes; and finally Billy Redding, a gay young man about town who kept an excellent store of "Gents' Furnishing Goods," and later vanished from town I have heard to larger business. Often there was a transient guest who liked the Junction House better.

We had food to eat, usually good and abundant, but there was no nonsense about cooking and serving. Underdone beef was not healthy. An egg was just an egg. Haddock fish, meat pie, fish and cream, oyster stew, hot biscuit, flap jacks, new maple syrup served in a saucer, pork and beans, boiled dinner, sausages, come to memory. No one could buy now such poor coffee as was offered three times a day.

There was a clerk who is memorable for his lack of authority and for his obvious suffering at having to sell three ten-cent cigars for a quarter. "Hod" took the night watches. That is, he had a sleeping room on the office floor. One night after the late train was in there was a noise in the office. Horace called out from his bed, "Who's there? What do you want?" The visitor replied, "Isn't this a hotel? I want a place to sleep." "Well," said Horace, "You take that lamp there and go up stairs and take the first room that ain't got anybody in it."

The Dartmouth Hotel went up in flames in the big fire of Jan. 4, 1887. South Hall, on South Main St., made a poor substitute until it was burned a year and a half later.

CHARACTER OF MERIT

It certainly surprises a modern to hear that the towering fire-trap, which in its going in 1925 threatened the whole village, was once the home of as prosperous and up-to-date livery stable as could be found Allen's stable. The old stage-coach driver knew his business, and if he did like to sit in the doorway of the big barn and sleep he was not easily fooled. A reckless student or an incapable of the faculty (for which body he had no respect) could get only a wooden beast impervious to all stimulants. But a real sport whom Ira trusted could have Jim or Dandy or Kitty and pass anything on the road. Mrs. Allen who collected the bills had a kind heart and made liberal discount. What Ira said to Dr. Leeds who tried to bring him to the meeting-house that if he wasn't there not to wait but go right ahead with the services—was a joy in the village for many a day.

Returns to Dr. Leeds' pastoral remarks did not always reflect the proper sentiment. In farewell to a resident who was moving away the Doctor said, "I shall probably not see you again on earth, but we shall meet in a better land," which brought the reply "I hope it won't be very soon, for I am pretty well satisfied where I am."

I suppose in olden times in every New England community there was a handy man, mother's helper, tinker if you choose, who would do anything desired about the house—restring the clock, set a pane of glass, open a trunk of which the key was lost. D. B. Pelton came near to filling this role. He was a carpenter by trade and had a shop on Cemetery Lane; he was also sexton of the College Church and lone and sometimes lonely policeman. As a faithful officer he once took into custody (and got him fined too) one of our young residents who has since won great distinction. His offense was not so much riding a bicycle on the sidewalk as giving too flippant a reply to an officer of the law when he was rebuked. As sexton heat and fresh air were part of his responsibilities. One evening I was very early at the midweek meeting. (Some old settler will tell inquirers what that was.) Pelton was in the breezy vestry alone. Said he, "I wish some of these folks who are always grumbling about fresh air and more ventilation would come here in the summer when I open the doors and all the windows and the Lord ventilates the place." He once assisted a kind elder sister in settling her brother in his room. The young man had once been a medical student and a little frisky. Although the sister told me this herself, with the addition that in her family nothing ever stood in the way of a joke, I do not give the true name. Pelton was putting down a carpet, and when he had exhausted the tacks in his mouth and stopped to take a good rest he looked up at the sister and said, "How the time does go by! It seems only a minute since I was arresting Fritsie."

And now meet Luman Boutwell, genial citizen, census taker in the Sunday School, master cabinet-maker and restorer of antiques. He could make or he could repair. Give him an old high-boy, an ancient gate-leg table or a dilapidated kitchen chair found in the shed and he could restore missing pieces with craft and polish it up so that it would be almost too shiney, or he could evolve a new one just as good. But his fame remained local and he never acquired riches because he played the cornet and also lacked any power of management or sense of time. You might take him an old bureau only requiring drawer pulls, and he would say that he guessed it would be ready tomorrow. Then if you went, proud of your effective wheedling, you would hear, "Well, I ain't got round to it yet. Come next week sometime." And if finally in three months you were able to extract it from the clutter of his workshop and place it before him with an injured manner, he might say, "Well, I declare I forgot all about it," and attend to it at once. One summer lady desiring to teach him efficiency took her knitting, or what stood for it, and spent three hours daily for three weeks in his shop. She got a leg put on her old footstool, but Luman good-naturedly grumbled that he did not like to be hurried that way.

WOMEN SHY OF CAMPUS

In those days when young gentlemen grew whiskers as soon as nature permitted and ushered on Commencement day in swallow-tailed coats, when women's ankles were an exciting sight and true modesty required one to say limb when meaning leg, some difficult questions of propriety arose. Should females cross the Green in the day time? Certainly not in the dark. This question was really settled by force, for certain valiant defenders of woman's rights habitually travelled the long diagonal of the campus, through two or three baseball games; and I have admired the chivalry of our young men in suspending all operations while the women slowly and defiantly made their way. It was debated whether the younger members of the faculty could gallop around after a tennis ball in plain sight of students and the public without great loss of dignity. The parliament waived the main question and reluctantly declared that they should wear their usual clothes anyway and not display their legs in knee breeches or swell the weekly wash with long white trousers. Worthen '72, came to the College as Tutor in 1874. Tutor, a position now obsolete, meant a young man qualified to teach anything, though of course it was unusual to put him into Evidences of Christianity or Psychology. Worthen was qualified to teach; he had shown it in the winter school. For he was the one who opened school with a challenge to the biggest boy to wrestle and afterwards got top wages for winter schools. Worthen's energy was superabundant and it was his pleasure to cut across the Green at any line and jump the fence. One day one of the oldest professors accosted him on the street, "Tutor Worthen, I notice that when you cross the campus you jump the fence; would it not look better if you followed the paths and came out in the usual way?" The class of '84 came out one morning in very neat greenwood costumes jackets and short trousers. One of the class actually had the temerity to wear this rig into recitation and was sent out by. the professor to dress himself properly. "Judge not that ye be not judged," fits well here. These were earnest conscientious people and they knew how to set forth a delicious supper on social occasions. The joke will be on us in the same way fifty years hence.

Let the ladies speak a little from an era when they were less in the public eye. The only business woman that I remember, Sarah Demman, offered hats to women where now is the bank. She could have joined "The Ladies of Cranford" without alteration, and was skilled in polite demolition. A lady came one day seeking becoming head gear. She spent a weary time going over the stock and trying on before the mirror. At last with vexation in face and voice she started to go. "But my dear" said the long-suffering Miss Demman, "you know you have your face to contend with." At another time a customer for whom she had little affection came in to get a patch to replace a small spot which rendered a dress unfit for use. The matter was of great importance, but after much turning over of stock and pleading for help the lady had to go away unsatisfied. Soon an assistant discovered plenty of the fabric wanted and told Miss Demman. "Yes," she said, "but I never can see anything when that woman is here."

I had acquaintance with the four or five young ladies who made up Hanover society. One evening a classmate and I took two of them coasting on River Hill. Ah, that was the sport; gone now! One of the ladies was afterwards a well-known author and gave me some of her books. I will conceal her identity by merely saying that she was daughter of a professor with a nickname that may have fitted his looks but did injustice to his kind heart, and sister of a younger brother who gave a large fortune, partly inherited from his sister, to the College for a beautiful building and for other fine purposes. It is, or was, well known that in packing a load upon a double-runner well-secured propinquity is essential to safety. My comrade, later a distinguished neurologist, took the helm and it fell to me as first mate to impart the initial impetus, that is to shove her off; and thereafter to secure a safe place on the moving projectile. As the ladies were my seniors I did-not know just what would be correct technique. Just at the moment of unstable equilibrium a gentle voice in front of me said clearly, "Now don't be bashful, Bartlett," and I knew just what to do for safety.

THREE OLD TIMERS

Three old timers differing greatly from one another I mention in conclusion, not because of eccentricity but because it interests me to recall them.

Ex-President Nathan Lord died in Hanover in September of my Junior year nearly seventy-eight years old. I often saw him sitting in the doorway of his house on Wentworth, the second from College St. With nearly eyery one else I was a unit in his funeral procession. It was then that Squire Duncan, Marshall-inchief made his famous remark. The procession halted. After a time one of the class marshalls inquired why they were stopping so long. Mr. Duncan replied with some bitterness, "Waiting for those damned old spavined trustees to catch up." Well, that couldn't be said now. This was told me by the one to whom it was said.

And there was "Prof." Haskell, "Professor of Dust and Ashes." At my earliest time he was the only full time employe of the College who did not teach. Imagine it! Most of the building of fires in the wood-burning stoves and the sweeping out but forgetting to dust was done by "indigent" students. Haskell was a sort of superintendent without much authority. He had to do the rescue work when a professor with his class was imprisoned in recitation room by screwing fast the door, or supervise the cleaning when the freshman seats in chapel were greased.

When I was in college William T. Smith was an invalid without occupation except giving some clerical help to his father the president of the College. When I returned seven years later Dr. Smith at the age of forty was just entering on his medical career. He was a successful and honored practitioner and became president of the New Hampshire Medical Society. Dr. Smith was one of those who like to leave their world a little better than they found it. So he gave to Wheelock's Church of Christ at Dartmouth College an appropriate communion table (which was saved from the fire), to the College a clock which faithfully measures out the hours of day and night, and for the village he transformed the ugly desolate road to the bridge into a highway arched with green, by planting trees. We may pertinently wish that

"his shadow may never be less."

OLD SANBORN HOUSE Croquet Wickets in Foreground

PRESIDENT NATHAN LORD

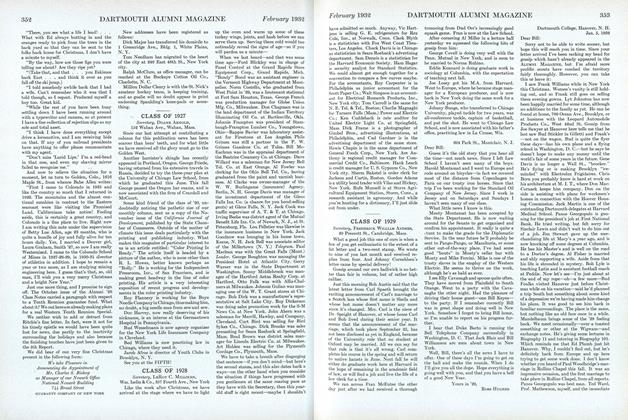

MOTIVE POWER OF OTHER DAYS Pratt 'O6 and Jennings 'O7 inside, with McDevitt 'O7 and others on the roof, "Dud" driving

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Article

ArticleModern Ski Technique

February 1932 By Otto and John W. McCrilis -

Class Notes

Class NotesCLASS OF 1926

February 1932 By J. Branton Wallace -

Class Notes

Class NotesCLASS OF 1905

February 1932 By Arthur E. McClary -

Lettter from the Editor

Lettter from the EditorWith Other Editors

February 1932 -

Class Notes

Class NotesCLASS OF 1910

February 1932 By Harold P. Hinman -

Class Notes

Class NotesCLASS OF 1929

February 1932 By Frederick William Andres