ALUMNI PRAISED

W. H. Morton '32 travelled to the West Coast during the Christmas vacation as one of the group of Eastern football stars who met and defeated a similarly representative Western team at San Francisco, January 1. The Eastern team made its headquarters at Palo Alto, the home of Stanford. Morton was the guest of the San Francisco Dartmouth alumni at one of their regular weekly luncheons. His comments on these phases of his interesting journey, as printed by TheDartmouth are quoted: "During the week spent in Palo Alto we had an opportunity to thoroughly acquaint ourselves with the Stanford campus and some of the members of the faculty and student body. Without exception the westerners were quick to laud the wonderful spirit that has grown on the part of Stanford men toward Dartmouth through the recent athletic relationships in football.

"Not only did the Indians from New Hampshire make a host of friends on their visit to the Coast in 1930, but they built up a relationship which Stanford hopes may be continued in the future. The Stanford football players spoke of the unprecedented hospitality of the Dartmouth alumni during their visit to Boston last fall.

"It was also my pleasure to attend the Dartmouth alumni luncheon, which is a weekly affair, in San Francisco. When 35 or 40 college men, three thousand miles away from their Alma Mater, are so vitally interested in the daily happenings at Dartmouth that they meet once each week to count over and discuss the various news reports and alumni dispatches sent from Hanover, it is certainly a glorious tribute to Dartmouth. I can see now the meaning of the President's description of Dartmouth not as a college but as a religion."

Bill's ascribing to President Hopkins the statement quoted above needs some qualification. Although the phrase has a familiar ring which may make it of some considerable age it is generally conceded that it was coined by Elmer Davis in a feature article published by the New York Herald Tribune, issue of November 14, 1926.

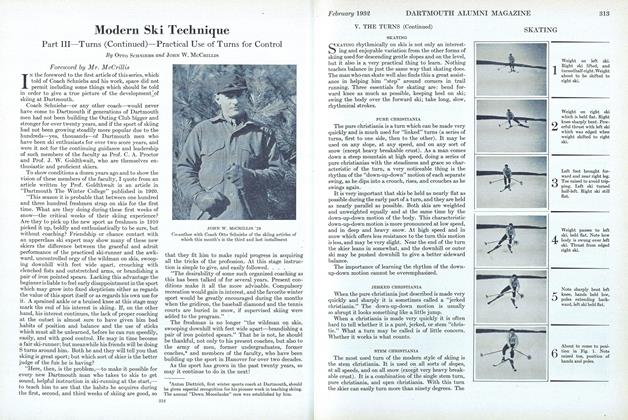

SKIING INSTRUCTION

The series of articles on "Modern Ski Technique" by Coach Otto Schniebs and J. W. McCrillis '19 have been reprinted in part by the Transcript and Herald in Boston together with a reproduction of some of the many photographs used to illustrate the series. The third installment of the articles concludes the series in this month's issue of the MAGAZINE.

Publication of the Schniebs and McCrillis material by the Stephen Daye Press of Brattleboro, Vt., is announced by the authors. The entire series printed in book form and profusely illustrated may be secured by ordering direct from the publisher.

INDIAN ECHOES

In the Stanford Illustrated Review for Janu- ary appear a number of articles descriptive of the Stanford-Dartmouth dinner, Novem- ber 27 in Boston, of the trip of the Stanford party to the East Coast, and of the game at the Harvard stadium when the western Indians scalped Dartmouth 32-6. Don E. Liebendorfer Stanford '24, director of ath- letic publicity for the university at Palo Alto, tells the story in an article "Indian Wars of 1931" of the trip east and the complete hospitality extended by the Dartmouth alumni of Boston. The Stanford-Dartmouth dinner is described by Charlie Field '95. Judge Brown's greeting in verse is also re- printed in the Stanford alumni publication.

Under the heading "A Grand Finale" the jtoicw. comments editorially: "Stanford is ready for a happy New Year, not so much from the fact that our football season ended successfully in Boston, as from the realization that the victory was appre- ciated in the land of our opponents. A few words from a Boston editorial received by Frank Keesling '9B, illustrate the respect which the Cardinal won from their generous hosts. In part, it says: "No team illustrates the fact that greatness often is obscured by failure to click, or appreciate power, so much as Stanford. Glenn Warner brought his team to the Harvard Stadium on Satur- day with defeats of 19-0 by Southern California and 6-0 by California tagged on its record. And yet Stanford, beating Dartmouth 32-6, had all the character- istics of a wonder team. . . .

"After seeing Stanford, Eastern critics wondered what the team had been doing all year and the only answer comes from the Stanford coaches and players them- selves. 'This was the first Saturday we clicked. We never played football like this before.' "

TO THE LADIES

In these cramped times when alumni funds shrink, the resources of the women's colleges probably grow more slowly than others. Such gifts as these of Mr. Morrow are indeed beneficial, kind, and illustrious.

Mr. Morrow's College Bequests

Friends of women's colleges who know their great need of endowments in compari- son with men's colleges take heart at such even-handed bequests as those of the late Dwight W. Morrow. He gave $200,000 each to Amherst, his own college, and to Smith, the alma mater of Mrs. Morrow and their daughters. It is an exceptional parity of benefactions and a chivalrous one, character- istic of the donor. It may be recalled that the original endowment of Smith by the will of Miss Sophia Smith was only $lOO,OOO larger than Mr. Morrow's gift to the college. It was from a professor's chair at Amherst that Smith took her first president, Dr. L. Clark Seelye. The neighboring colleges ever since have been linked by sentiment, collective and individual; they are equal in the affections of many families like the Morrows.

If the women's colleges are to receive their share of financial support it must come largely through men's assistance, for the alumnae as a body have not great means at their command. The high quality of the women's institutions, their splendid service to education and the enrichment of life are continually praised, yet sizable gifts and legacies to them by prosperous masculine well wishers have been few. Mr. Morrow's example is most welcome, as it may set others thinking that the neglect of the women's col- leges should be repaired.—N. Y. Herald-Tribune.

FASHION NOTE FROM PRINCETON

Full dress has been the almost unanimous choice of prom-attenders here for several years, but it is interesting to note that this is the only concession the boys are willing to make to the formality of campus social life. A few of the boys give way to white gloves, and the sticklers wear top hats, but they still seem a little incongruous on Nassau Street. No evening canes to date.—Princeton AlumniWeekly.

THE AMES' PROPOSALS

Professor Ames' bulletin, "Progress and Prosperity," by its intelligence, timeliness, and scope aroused widespread editorial comment. Following are two representative opinions:

The Dartmouth—Jan. 8 PROGRESS AND PROSPERITY

In these depressing times when blue Mon- day comes daily it is good to hear a word of intelligent hope, for it is intelligence and thought coupled with honest endeavor that will in the end turn our blue days to blue skies. For this reason we turn again to Prof. Adelbert Ames' pamphlet on "Progress and Prosperity" which has already been referred to in these columns Professor Ames has done something more than propose a political panacea; he has put into print a factual analysis of our present situation, analyzing its causes and suggesting the trend that a remedy for our financial illness must follow to be effectual. . i

American capitalism is wavering and it seems at present to be a question of time be- fore it totters and falls as have the capitalistic systems of those former monarchies of which Russia and Italy are prominent examples. There undoubtedly is something fundamen- wrong either with capitalism or with our present interpretation of capitalism based on the theories of Smith, Ricardo and Mill. The solution to our problem if it is to be at all enduring must effect some kind of a change in our present system. Whether this change is to be some form of socialistic dictatorship or something entirely new, or whether it is to be an adaptation of capitalism as it is now understood is the question that must be answered in the near future. Professor Ames has suggested in his pamphlet that we should change our concept of capitalism, at least insofar as to the application of its principles to our economic life. He explains that the fundamental reasons for our cycles of depression is an apportionment of capital and labor that is basically wrong inasmuch as it allows overproduction and fosters periodic depression.

This treatise of the subject is one which may well interest the undergraduate. Not only does it bear directly on our economic lives but it is written clearly and well and is absorbing even to the laymen. It lacks the maze of entangling phrasing and reasoning that makes the study of economics' difficult for the neophyte. And it is decidedly not a text book. We, therefore, suggest that those who are interested in finding a solution to the problem which confronts this country and the other nations of the world take the trouble to secure and read Professor Ames' suggested program for the return of prosperity.

The Boston Herald Jan. 6

WANTED: AN INVENTION

Adelbert Ames, Jr., professor in the Dartmouth medical school, has written a little treatise entitled: "Progress and Prosperity: A Suggested Program." It is issued as a supplement to the Dartmouth Alumni Bulletin. Dean William R. Gray has written a foreword in which he welcomes "the privilege of commending Prof. Ames's paper to the thoughtful and critical consideration of all whom it may concern." Philip Cabot, professor of public utility management at the Harvard business school, says that the Ames sketch, "if carefully studied by competent men, might furnish the basis for a successful national policy."

A copy reader of a New York newspaper summarizes the essay as follows: "Economist finds unemployment may be blessing." The average person would probably epitomize it somewhat differently. He would be inclined to say that Prof. Ames has no expectation of a return of prosperity until there is a great discovery or invention or a series of them, comparable to the printing press, steam engine, railroad, telegraph, telephone, electric light, electric motor or automobile. In the words of Prof. Ames: "There is but one conclusion to draw and that is that new developments are the life of economic prosperity. If this is so, then, without a steady flow of new developments prosperity cannot return or be maintained."

Prosperity comes only when new demands are created, says Prof. Ames. The need is for new developments which enable individuals to do more in less time, and which increase the people's capacity for economic activity. The replacements which follow are made necessary by obsolescence and are not enough they merely keep economic well-being in statu quo.

And how would the Dartmouth professor bring about these developments? "By diverting capital to the field of development." He would place less capital in replacements, and more in research laboratories. By exemption from taxation and allowing large profits, and by other means he would so stimulate the imagination of men that they would seek new inventions of general utility more intensively than at present. He would have the people educated and trained more carefully.

Just-as interesting as the theme of Prof. Ames are the remarks of Prof. Cabot. He is impatient at the classical economists. He thinks that we are at the parting of the ways and that unless we can find new methods, our progress may be at an end. He says: "... Heretofore such doubts have been confined to socialists and radicals; now they are coming from the capitalists themselves. Our practical business men know, for example, that the so-called law of supply and demand . . . works about like the Volstead act; that the law of monoply profit went into the discard years ago; and that the law of diminishing returns is, for the business man, with science as his tools, merely the law of diminishing brains. . . . Obviously the old capitalist system has developed vices which must be corrected or they will destroy it; less obvious, but not less true, is the fact that both socialism and communism have seen their best days. What we needed was a new philosophy of capitalism socialized so as to fit the conditions of the, present day. We have it here. Prof. Ames has seen the 'star in the East.' "

Here, then, are three men of solid reputation who are voicing a complaint similar to that of Dean Wallace Donham of Harvard in his well-known volume, "Business Adrift." Prof. Ames's essay is not easy reading nor is the Donham book but the layman will catch sentences here and there which will shake him free from some of the ideas which he has accepted heretofore as without question. The fact that these three contributions have been issued as a supplement to the Dartmouth publication suggests also the wisdom of looking them over.

"TALKIES" FOR EDUCATION

Under a grant of $25,000 by the Carnegie Foundation the Harvard University Film Foundation and the graduate school of Education are exploring the teaching possibilities obviously present in the development of films in sound. The talkies as a commercial venture have proven to be successful. Improvements in both filming and sound effects may be expected as technical proficiency increases. Leaders in education realize the value the talkies will have in the teaching of the future.

Some months back President Hopkins was the guest of several New York movie producers, including Walter F. Wanger '15, at a preview of talking pictures developed in the experimental work now being done in the interests of educational talkies. Dartmouth is watching the experimental phase of this new factor in teaching with interest. Especially is the work being done at Harvard of importance.

The latest research in this field at Harvard is described by the Boston Herald in an editorial entitled:

Teaching by " Talkies"

An experiment in education, as carefully conceived as a project in a chemical laboratory, is beginning this week in the junior high schools of Lynn, Quincy and Revere. Two groups equal in intelligence and taught by teachers of the same ability will study a course in elementary physiography and biology. One group will pursue the usual classroom method of instruction by teacher and textbook. The other will have this instruction supplemented by talking motion pictures. At the end of the course, the groups will take the same examination.

The outcome should indicate tentatively whether the introduction of films into the classroom is justified in terms of increased knowledge.

The officers of the University film foundation and of the Harvard graduate school of education, who are making the test under a $25,000 grant from the Carnegie Foundation, fully expect, of course, that the boys and girls who have seen and heard the films will excel in the examination. They maintain that the average child has an inadequate background for the more advanced subjects. In geography, for example, he is expected to remember a great many facts about places which he has never seen and which his parents probably never saw. The film, however can bring to his most important senses sight and sound all of these strange parts of the globe Africa, Thibet, the Arctic and so on and make them live in the very room in which he sits. Coupled with explanatory comment by an authoritative speaker, they are likely to be more illuminating than the printed page and illustration.

The advocates of the films would probably concede that a trip around the world would teach even more three months in France is easily worth three years of French in the usual school! but the cost of such a trip is generally prohibitive. Thus the value of the talking films will also probably have to be decided by dollars and cents. Fortunately, the cost of the projection machines and sound equipment has been reduced greatly in the last year or two, and their installation seems a modest experiment in comparison to swimming pools and the other elaborate accessories of the modern high school. If the film-taught children in Lynn, Quincy and Revere display an emphatically clearer understanding of the subjects than their brothers and sisters, the school committees in those communities may revise their methods. If the difference between the two groups is hardly noticeable, the cinema will probably continue to be considered an educational luxury.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Article

ArticleOld Timers

February 1932 By Professor Emeritus Edwin J. Bartldlett -

Article

ArticleModern Ski Technique

February 1932 By Otto and John W. McCrilis -

Class Notes

Class NotesCLASS OF 1926

February 1932 By J. Branton Wallace -

Class Notes

Class NotesCLASS OF 1905

February 1932 By Arthur E. McClary -

Class Notes

Class NotesCLASS OF 1910

February 1932 By Harold P. Hinman -

Class Notes

Class NotesCLASS OF 1929

February 1932 By Frederick William Andres

Lettter from the Editor

-

Lettter from the Editor

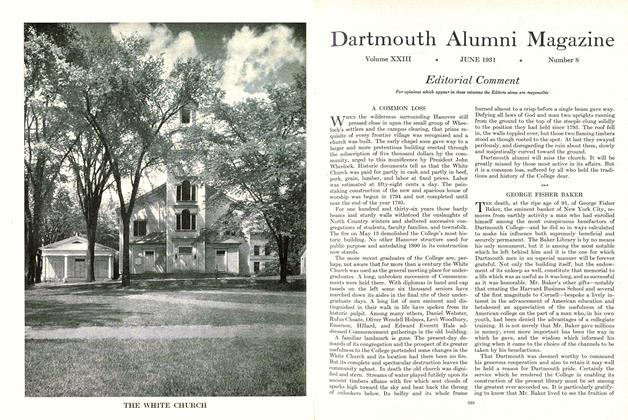

Lettter from the EditorEditorial Comment

January, 1930 -

Lettter from the Editor

Lettter from the EditorEditorial Comment

June 1931 -

Lettter from the Editor

Lettter from the EditorDartmouth Manuscript Series—The First Volume

MARCH 1932 -

Lettter from the Editor

Lettter from the EditorDouble Vision

MARCH • 1985 By Douglas Greenwood -

Lettter from the Editor

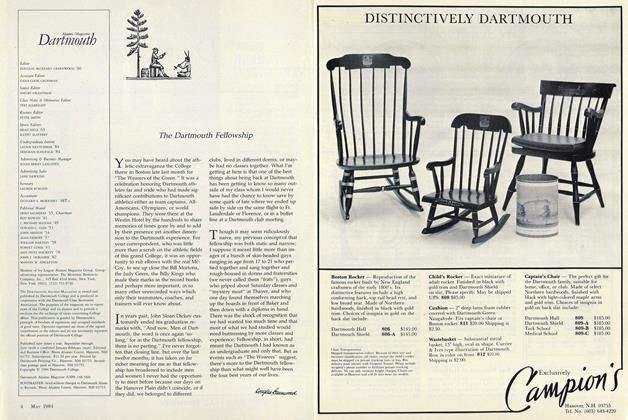

Lettter from the EditorThe Dartmouth Fellowship

MAY 1984 By Gouglas Greenwood -

Lettter from the Editor

Lettter from the EditorWhat's a Humane Letter?

February 1939 By JOHN PALMER GAVIT