THE name of Powers means much to a student of the history of the upper Connecticut valley. In 1754 Captain Peter Powers of Hollis, N. H., was sent to explore the part called the "Coos Country" and was the first to leave an authentic account of that region. In this same year, 1754, his eldest son, Peter, was graduating from Harvard, and ten years later was settled over the church formed of Newbury and Haverhill, and thus became the first pastor in the Coos. He labored up and down the valley until the other clergymen came. An incident of his duties was the performing of the first marriage ceremony in Hanover.

It would have given him pleasure could he have known that another of the name, his nephew, Grant Powers, would be his successor in Haverhill, and also the first historian of the region in writing the little book called "Sketches of the Coos Country."

Grant Powers was born in Hollis, N. H., March 31, 1784, and graduated from Dartmouth in 1810. He then read "Divinity" with Dr. Asa Burton of Thetford, after which he held the pastorate at Haverhill and a second one in Goshen, Conn., where he died April 10, 1841, aged fifty-seven. His father was an intelligent farmer of Hollis and his mother belonged to the well-known Abbot£ family of Andover, Mass., a family connected with the establishment of educational institutions which have since become famous.

The manuscript, from which the following quotation are made, was written by Mr. Powers in his last days, for the benefit of his family. His descendants have kindly allowed it to be used in the preparation of a history of Thetford, Vermont. It is a moving account of a useful and devoted life in the first half of the nineteenth century, and as so much of that life was lived in the vicinity of Dartmouth, portions of it are of particular interest to Dartmouth men.

FROM GRANT POWERS' DIARY

"As he (his father) had no more property than would insure him and my mother a comfortable maintenance through life, connected with their own industry, he told his sons as soon as they came to fifteen years of age, they might have their time if they would select their business, and make good use of the time till twenty-one years of age, but at the same time, uniformly said, placing his hand upon my head when I was small, 'Grant must stop with his father and mother and see them through life.' I accordingly stayed with my parents until my youngest brother left to try his fortune.

"I was now eighteen years of age and did the whole business on the farm, as my father had become an invalid. But manual labor was no more than sport for me, as I hardly knew what sickness was, and at seventeen could take a barrel of cider or water, and put it into the tail of a cart without any foreign aid. The same summer that I was seventeen I performed a full day's mowing for old Mrs. Zachariah Shattuck of Hollis in four hours and thirty-five minutes. And in truth, I may say that at this time I gloried in my muscular powers, and had often wondered that a person could be so reduced as to find it difficult to breathe."

PREPARING FOR COLLEGE

We pass over the story of the next four years. They were filled with hard work, perplexing problems and an exhausting emotional and religious experience. Changes in the family left young Grant Powers free at the age of twenty-one to plan his own life. He supposed it was too late to think of an education and made arrangements to learn a trade. But he unexpectedly met an old friend who had decided to strive for an education "and he was greatly determined that I should enter upon the like adventure. My reply was that such a thing as that was impossible. I could conceive that he might do it, as he was already a scholar, had rich parents and some money to commence with, but I was no scholar or had ever enjoyed but few means for an education, had no friends who could assist me, and no money. But he endeavored to obviate all my objections . . . and proposed that we should go to our minister, the Rev. Eli Smith, that night and take his advice. It was a late hour, and the walking very bad, as the frozen ground was like hatched teeth. We reached the house of Mr. Smith a little before eleven o'clock at night, and Mr. Smith was undressing to take his rest. He seemed much surprised to see us and sat down upon the side of the bed and waited for announcements. My friend, with some embarrassment, stated the object of our coming at that unreasonable hour. I kept silence. Before he had done Mr. Smith seemed to comprehend the whole subject and espoused the cause of my friend with all his native energy, and before we left "Mirabile dictu" I had resolved on striving for an education. . . . "It was shortly arranged that I with three other young men should all commence our studies at the Rev. Mr. Smith's on the same day. I was to enter upon English studies and they upon the Latin. But I had neither book, slate, or pencil, and I borrowed thirty-seven-and-a-half cents of my oldest sister and bought me a slate and pencil.

"One of these young men had a portion of 1500 dollars at his command, another had 700 dollars, another about 200 dollars, and I was cents below level.

"When I came there it was thought best for me to commence Latin with the others, and Mr. Smith furnished me with a grammar.

"We all applied ourselves closely, and the second day, the young man who had the most means deserted our company and never returned to us again. We went through the Latin grammar in ten or twelve days, and before we had proceeded far in Fables, my two companions had opportunity to engage in school keeping, and they left hie.

"I then took my slate and pencil, and English studies, for I knew very little of reading, spelling, writing, arithmetic, or English grammar.

"By the middle of February Mr. Smith said I could teach school to good acceptance, and he engaged a small school for me in the south part of Milford at ten dollars per month and furnished me with a certificate. I have always wondered at this, for I was profoundly ignorant of every branch of education. But I went on and kept the school and was so immensely popular that they engaged me for the next winter at $12.50 per month."

SCHOOL AND COLLEGE

During the summer lie worked on farms and in the fall went to Groton Academy (Mass.) for a time where he "got some insight into arithmetic and English grammar, and could write tolerably well." Of the early winter he says, "I taught seventeen weeks in three different schools in two different states and the extremes were thirty miles apart, but did not lose a day, for as soon as one closed, the other was ready to commence and walking all day on one Saturday enabled me to be upon the ground at the time appointed."

He then had an opportunity to go to Phillips Academy and while there he lived with his great uncle Samuel Abbot "who needed a person to read for him, and at times to ride with him. . . . When I left for Hanover College, September, 1806, he gave me eight dollars, and I hired thirty-five dollars of my brother Joel. This enabled me to spend the first term in College and during the winter I taught the Central School in Hollis, twelve weeks, at twenty dollars per month. This was great wages for those times for they were Embargo times, and under the administration of Mr. Jefferson, and dollars were very scarce. But I had a large school of ninety scholars under examination at once. The avails of my labors this winter carried me through the summer of my freshman year, but as the times grew more and more hard I could see no way by which I could procure means to meet the expenses of the approaching fall term, and yet I did not despond for I had already got the impression that there was a superintending Providence that provided for me, independent of myself.

"It so turned out that at the Commencement of 1807, I was the only freshman, who had a part in a play for the evening before Commencement. It was a tragiccomedy exhibiting the Irish Rebellion, in which the Established Church of England bore a conspicuous part, I belonged to the Establishment, and the design of my part was to show the cruel and oppressive nature of the Establishment, and so it was General Stephen Abbot of Salem, Mass., was there, himself an Episcopalian; but he was so much interested in the part that I performed, that he inquired me out, and found he should go by my parents on his way home, although I did not speak with him at Hanover. He came to my father's on his return, and called in my absence, stated what he had witnessed at Hanover, and although said he, 'he took me off, yet it was done so well, I was resolved to see him.'"

A BENEFACTOR APPEARS

"He inquired how I was supported at College, and soon I came home and before I entered the room, he, hearing my voice, came out to meet me, saying, 'Sir, I saw you at Hanover a few evenings ago, and you gave us poor Churchmen a severe drubbing, but it was well done, and now I wish to know what are your means for going back to College.' I told him I had none. 'How much do you want?' I told him I thought I might get along with forty dollars. He drew out his pocketbook, threw it on the table saying 'There, count it out, and then get you a pen and paper and write me a note.' I replied to him 'General, I have no means, and if I should prove a villain, or should be taken away, you have no remedy.' At this instant my father was affected at what he heard and came forward and said, 'Grant, I will sign with you.' 'No,' said the General, 'You shall not. He shall be alone responsible. I know what I am about.'

"I counted out forty dollars and called for pen and paper, and then he added, 'You will feel better with ten dollars more, count it out.' I did so and gave him my note. He then took up his pocketbook, and shaking it at me, said, 'When that is gone, remember, here is more. Come again.'

"You may judge of my astonishment at this unexpected supply, for that was not an age of benevolent acts like the present.1 There were no Educational Societies, Bible, Tract, or Missionary Societies like the present. General Abbot, although a liberal man in his house, and would send portions of good things to the poor in town, never did much, as I can learn, for general objects of benevolence. His education did not qualify him to appreciate the advantages of science, and I do not suppose he thought himself an experienced Christian, although a member of the Episcopal Church.

"And more than all, I was not sure that Christians would have selected me for an education, for I was not professedly pious."

Mr. Powers had more experiences, pleasant and unpleasant, in teaching and came to the last year of College, when he taught successfully at Royalton, Vt., during the winter vacation.

"Would any know how I could be absent from College for so long a period of each winter? I will state that at that time there were but two vacations in the College in the year, four-and-a-half weeks from Commencement in August, and eight-and-a-half weeks in the winter. This was an arrangement to aid those who were under the necessity of keeping school. And I always carried my Classics with me and kept up with my class and passed an examination in the spring.

"When this was known by the Faculty, they were not rigid with me as to the time I was absent, and I recollect perfectly well, that as I returned in the spring from Royalton in 1810, I was examined by the President, with several others who had been out eight weeks or more. And when we had been through with what the class had studied in our absence I remarked to the President that I had been paying some attention to Chemistry and should like to be examined in that. He manifested surprise and approbation, and after a few simple questions, dismissed us, for that was not a classic in College; and the President himself was not proficient in that science.

PROF. NATHAN SMITH

"But I had an object in applying my leisure hours to that branch of science, as I had already resolved on being a physician, and surgeon in my future life. To this I was invited by Prof. Nathan Smith,2 and for two years he had aided me in granting me attendance on his lectures, gratis, and in leaving with me the key of his Anatomical Museum, so that I could enter there with my book and read Anatomy with every part of the human system exhibited before me. My name was already enrolled in his Catalogue of Students, and I was uniformly called to attend with his students, when an operation was to be performed on the Plain or in the vicinity. I was exceedingly fond of that study in this profession, and I had the vanity to think that I never saw him perform any operation which I could not have performed after him.

"I mentioned this fact to him after I was in the ministry, specifying one thing to which I had doubts. 'What was that?' said he. I referred him to the amputation of a limb in the town of Thetford and recalled to him the trouble he had in taking up the great artery. 'o' said he, 'Yes, I remember it. Ah, that was an extraordinary case. I never saw anything like it before or since. You would not experience any difficulty in that in most cases, and I presume you would have operated successfully in almost every case, when you had once seen it performed.' And it was always his belief, as I learned from others, that I ought to have pursued that Profession."

SERIOUS ILLNESS

"But I have arrived to serious and portentous ground. In the winter of 1810, at Royalton, I took a violent cold on my lungs, which produced a very hard cough, and it was almost incessant, but I paid no attention to it, until by continued exposure it became fixed upon me.

"I returned to College in March with it, in hopes it would leave me, when shut up in College; but it continued nearly the same until the first of May, when I was to return to Royalton to Preparation School for a public exhibition in June. The only difference was my loud and hard cough had subsided into a low incessant hacking cough and I was feverish and weak. But I knew no other way for me than to labour and throw off complaints as I had always done, and I did not dream of anything serious, although had I seen another in my condition I should have preached terror at once.

"I continued to instruct till after the exhibition. I then thought I would journey for my health."

Mr. Powers "mounted a hard trotting horse" and rode forty-seven miles the first day. After some days of this he gave out completely and his life was despaired of.

"Dr. Smith soon came to Royalton and told my friends that my case was hopeless, but all three (doctors) agreed on depleting me as far as could be done and not have nature fail under it. They took blood until I could hardly speak. They continued blistering and put me on fasting. I lived on milk and whey without bread.

. . . My pulse was uniformly 120 strokes in a minute. My breathing was short and labored and pains confined my lungs to a small compass."

In August he had rallied enough to be able to go to his parents' home by chaise with a devoted friend.

"I took my leave of all for this world. We went by Hanover and the Professors asked me some questions and told me that they should confer on me my degree of A.8."

REV. GRANT POWERS of the class of 1910

Written in 1840. 2Dr. Nathan Smith, Harvard M.B. 1790, established the Dartmouth Medical School, the fourth in the country, in 1797.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Class Notes

Class NotesCLASS OF 1929

May 1932 By Frederick William andres -

Article

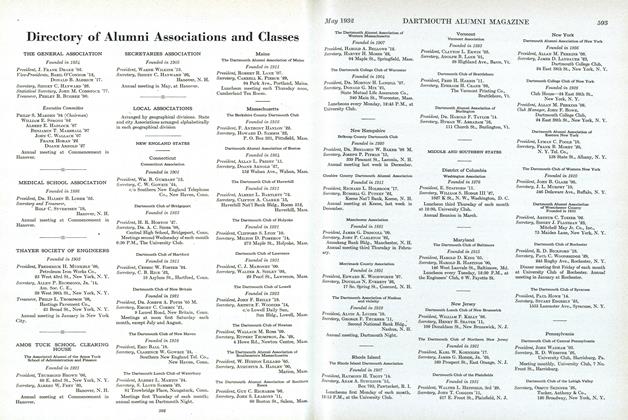

ArticleDirectory of Alumni Associations and Classes

May 1932 -

Lettter from the Editor

Lettter from the EditorPublic or Private Schools: A Letter to the Editor

May 1932 By Louis P. Benezet -

Class Notes

Class NotesCLASS OF 1905

May 1932 By Arthur E. McClary -

Article

ArticleLetch worth Village—A Home for Mental Defectives

May 1932 By Charles S. Little, M.D. -

Class Notes

Class NotesCLASS OF 1910

May 1932 By Harold P. Hinman

Article

-

Article

ArticleRhodes Scholarship Appointment

January, 1911 -

Article

ArticleMasthead

January, 1912 -

Article

ArticleCarol Service Resumed

January 1945 -

Article

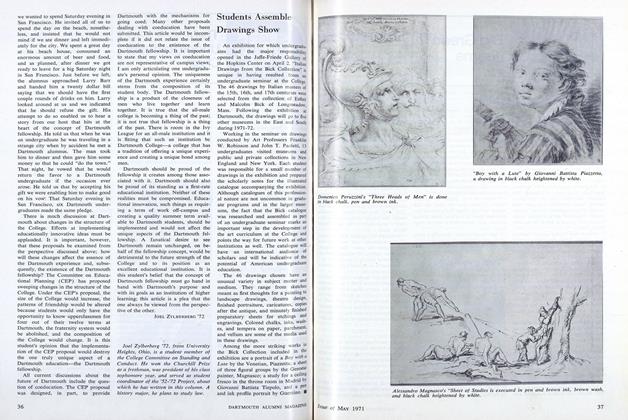

ArticleStudents Assemble Drawings Show

MAY 1971 -

Article

ArticleThe Teaching College

May 1994 -

Article

ArticleAlumni Council Sponsors Southeastern Conference

December 1953 By RICHARD D. McCARTHY '50, ATLANTA CLUB SECRETARY