THE writer quarrels with four of the editorial state- ments;—one, that there is an "occasional pro- pensity among public school products to outstrip the products of the private schools." Two, that it is "very unlikely that public school preparation is even so good as that which a similarly minded lad would derive from a private school." Three, that "the differ- ence is probably in the boys." Four, that "the teaching in them" (the private schools) "unquestionably is better than that in public schools where politics holds sway." (Note that the absence of the comma restricts this to a small percentage of public school systems.)

The first statement is refuted by the opening sentence of the article, which tells the truth;—"it is the virtually universal testimony" etc., that the public school products stand better scholastically than the graduates of private schools. The results of a study made in 1925 were published in the Daily Dartmouth, to the effect that while only fifty-six per cent of the Dartmouth undergraduates had been prepared in public schools, seventyeight per cent of the men in college who were outstanding for scholarship or leadership were public school graduates. Similar studies from Princeton, Yale, Harvard, and Smith confirm this conclusion.

The second statement can be nothing but a guess. Each person will answer it on the basis of his own prejudices. The editorial states that the young people who go to college from the public schools are "the picked few." This was true thirty years ago. Over two hundred graduates of the two Manchester high schools entered institutions of higher learning in the fall of 1930.

The statement that "going to college is the general rule for all products of private schools" is far from true. There are any number of military academies which send very few of their graduates into college and scores of institutions of the type of "Miss Blitheringham's Finishing School for Girls, at Lorgnette-on-the-Hudson" which do not pretend to fit for anything but a fashionable debut. Sixty per cent of the graduates of the Manchester high schools eventually go to higher institutions of learning.

Speaking of "preparation," are we thinking of preparing for the first semester of the freshman year in a New England college for men, or preparation for the work which the young person will follow as a life vocation, and for worthy citizenship, which is a very different thing?

The average private school offers a hide-bound curriculum, forced upon it by the requirements of certain colleges whose educational thinking is still back in the mauve decade. The underlying philosophy of education in the "Gay Nineties" was the doctrine of formal discipline, that if a boy is compelled to do hard and unpleasant memorizing, such as the principal parts of irregular Greek verbs, or the development of the "e" formula for logarithms, this will give him a very keen brain. Totally exploded long ago, this theory still dominates entrance requirements at many colleges and dictates curricula for students of secondary schools.

A Pacific- Coast university admitted thirty mature students who had never attended a secondary school, but had proved by an intelligence test that they had better than average thinking ability. This unprepared group, older than the average entering student to be sure, ranked, as freshmen, considerably above the average of the class.

Dartmouth is very liberal, with English and Mathematics her only prerequisites. Many colleges are still very narrow. They declare that a study of the life activities of Gladstone, Gambetta, von Bulow and Crispi does not fit a student to do college thinking; while a study of the careers of Alcibiades, Cleon, Parmenio and Gelon is essential to any further pursuit of higher education.

Some years ago I recommended a boy to a college which we will call Wilson. The boy's course in history had emphasized Modern European rather than Ancient History. He had studied Ancient History a half year instead of a year; therefore Wilson turned him down. Their statement to me was that there were plenty of desirable boys so anxious to enter Wilson that they would spend one year on Ancient History; therefore, why should Wilson change? The boy went to Harvard, where he is making a brilliant record.

The entrance requirements of another college, which we will call Abercrombie, are as follows:

"4 units of English; 4 of Latin, or 3 of Latin plus an extra unit of advanced Mathematics or a third year in a foreign language; 2 units of Algebra; 1 of Plane Geometry; 2 of a foreign language; 1 of Ancient History; plus two electives, preferably 2 more years of a foreign language."

Any private school which advertises to prepare boys for all-New England colleges is practically confined to this course.

Now let us take a look inside the head of a boy who enters college with the Abercrombie preparation.

He knows the story of: Diogenes and his lantern; The Spartan boy and the fox; The geese that saved Rome; Claudius and the sacred chickens; Caesar and the Rubicon; Alexander and the Gordian knot; Nero's fiddle and his fire; Horatius at the bridge; Caligula's wish that the Roman people had only one neck;

He is ignorant of the: Anglo-Saxon invasion of England; Norman conquest; Story of the French Revolution; Commonwealth of Oliver Cromwell; Career of Napoleon Bonaparte; Congress of Vienna; Republic of Spain; Unification of Italy and Germany; Causes of the World War; Foundation of the League of Nations and what it stands for.

He is well acquainted with the following 'persons: Cerberus Sisyphus Castor and Pollux

Aristides Miltiades Pelopidas Numa Pompilius Catiline Philip of Macedon Antipater Coriolanus Zantippe

He is ignorant of: Philip Augustus Wyckliffe Francis Bacon Spinoza Rene Descartes Richelieu Gustavus Yasa Peter Romanoff I Mirabeau Metternich Bismarck Poincare Briand Gustav Stresemann Andre Tardieu James Ramsay McDonald

He is well acquainted with the: Second periphrastic conjugation; Hortatory subjunctive; Gerund and the gerundive; Ablative of specification; Pythagorean proposition; Binomeal theorem with fractional and negative exponents; Convergency and divergency of series; How to divide a line into extreme and mean ratio; Dactyllic hexameter acatalectic;

He is ignorant of the: Story of vaccination and inoculation against disease; Commission and city manager form of government; Evils of selling short and buying on margins; Story of the industrial revolution; Scientific facts behind the invention of wireless telegraphy and radio; Simplest principles of bookkeeping and banking; Common laws of healthy living.

A certain boy is preparing for Dartmouth in one of our high schools. His English work has given him an appetite for reading. He is not forced to analyze Burke's Speech on Conciliation with America, Macaulay's Essay on Addison, Carlyle's Essay on Burns and similar thrilling classics of the college entrance list. He is learning to write original stuff. He is reading modern plays and playing parts in them in the school's dramatic society. He has had general science, biology, chemistry and physics; modern European history, United States his- Tory from a social and economic standpoint, three years of mathematics and three years of French. He knows his irregular verbs and writes an acceptable letter in French. He can pronounce French in a way to make himself understood by the French.

Other students in our high schools, preparing for college, take Sociology, Economics, Community Civics, Musical Composition, Harmony, Graphics, Art, Journalism, Hygiene, Home Economics and other subjects which have to do with things that are happening here and now in the United States. Few private schools dare include such subjects in their curricula. They are confined by the requirements of Wilson, Abercrombie, Jones, etc., to Latin, Mathematics, Modern Language, etc., as listed above.

Of course, one can not lump all private schools together. There are fifty-seven varieties. One group are among the leaders in progressive education. They are so liberally endowed that they are independent of college requirements and can teach anything they wish. They are usually day schools with a long waiting list of applicants and therefore have no problems of discipline. At the other end of the line are some military schools which are only a few steps removed from a state reform school, both in their clientele and the methods which they must use in order to keep discipline over such a group.

There are some families whose children have always gone to private schools: it is expected, as part of the family tradition, that the sons shall go to St. Timothy's and the daughters to Perry Hall. On the other hand, the great bulk of recent private school accretions has come: one, where hedonistic parents have refused to assume any responsibility for the rearing of their offspring; two, from homes where parents have failed in their effort to make their children study in public high schools (in the private school there is no car for them to hop into after supper, but, instead, a study hall where quiet is enforced for two hours every evening); three, from children who are not ranking quite high enough in the public high school to make the eighty-five per cent which is the certificate grade for certain very desirable colleges. Such children are sent to private schools which exist by preparing mediocre students to pass college entrance examinations with sufficiently high marks.

There is a place for the private school. It is needed to supplement, by an extra year of preparation, the work of some small high schools which are limited to a single course which would not satisfy Wilson and Abercrombie. It renders a service by giving an additional year to the high school graduate whose parents consider him too young to enter college. It is a godsend to the unfortunate children referred to under "one" above. Many a master in a private school has supplied to some small boy the affectionate interest refused by his parents. The private school does a great deal for those children whose parents have fallen down on the job of controlling them. Many a child who might have been ruined by his parents has been made into a decent citizen by private schools. The private school also has a distinct function under the third heading. It knows how to beat certain rigid entrance examinations. It plays the old game of palming off on the colleges second-class intelligence as first-class. You remember how Kipling's Head takes Stalky aside and teaches him how certain answers will, please certain examiners. For years certain schools have made it their business to decode the minds of those who make out the entrance examinations. They know what type of questions will be asked and they drill their students how to answer them.

I once was teaching in a private school which had guaranteed to get certain boys into Dartmouth. At graduation time it was discovered that someone had blundered and that one boy was short a credit in science. We secured copies of the five previous entrance examinations in physics given by Dartmouth. I wrote out the correct answers to these questions and the boy memorized them. Five of the seven questions on his examination came from my list and he was admitted! I blush to recall it now, but the school had to be vindicated.

With this clientele, it is inevitable that students in a private school must be always under a strain. They must pass the college entrance requirements, or the school will lose students, money, and its reason for existence. Boys are driven through distasteful subjects; in many cases they are given in advance a great deal of the work which they will encounter in their first college term. This carries the student through the first college semester's work successfully, and the honor of the school is saved. Then the impetus is gone and the student is more likely to slide down hill, scholastically, than is the high school boy who, according to Dartmouth's statistics, does progressively better work throughout his college course. Which student has the better preparation?

Three: The editorial says that "the difference is probably in the boys." There is a difference, of course. There are two kinds of private schools: first, those which are financially embarrassed and which, therefore, will admit any boy whose father has the price; second, those which are wealthy enough to exclude applicants considered undesirable. In the first type, the headmaster must keep enough boys to provide the money to pay the teachers' salaries. He cannot afford to see every infraction of the rules. He cannot make life unpleasant for the boys, for they might leave him; and yet, at the end of the year, he must explain to the parents why these boys were not admitted to college. His is a dog's life.

The wealthy schools are better off. Yet, as keen an observer as Sir Philip Gibbs, in "Since Then," writes:

"There is no discipline, I am told, in those very expensive private schools established for the sons of millionaires or highly successful business men. The buildings are magnificent. Every comfort is guaranteed. The teachers are men of education and culture—some ,of them imported specially from Europe. There are wonderful gymnasiums, the campus is beautiful, the technical equipment is magnificent and costly, as I have seen with admiration. But there is no discipline, they tell me, such as prevails still in English schools. The boys have too much pocket money. They play poker in their dormitories. They smuggle in books and pictures which are not exactly edifying to the mind of youth. They laugh at the admonitions of anxious teachers—those oldfashioned guys—who are not allowed to give them a flogging, as in English schools, and are afraid of expelling a black sheep lest it bring scandal upon the school which, must be made to pay. It is very difficult in this age of rebellious youth."

There is a difference in the boys, but not the difference which the editorial infers. The first difference is between the environment and influences that have surrounded them during their preparatory school life.

Four: The editorial states that "the teaching in the private schools is unquestionably better than in the public schools where politics holds sway." This, as I have already pointed out, is a very small fraction of public school systems. I have been connected with six such systems and I have yet to see a teacher appointed for political reasons. I have heard stories of one or two Massachusetts cities where political influence is necessary in order to secure an appointment, but even in these systems the long arm of the State Department is felt. Teachers cannot qualify for state certificates without certain diplomas, certain hours of practice teaching, certain standards of character and ability. State inspectors visit all the public high schools and insist on the dismissal of incompetent teachers. If it is not done, the school loses its privilege of certifying its graduates to state institutions and principal and superintendent lose their jobs immediately. In the private school there are no rules, no inspection, certificates, or standards other than the will of the Head. I can think of several schools where a place has been made for Aunt Mary's brother-in-law and Cousin Sarah's husband, or the nephew of the chairman of the board of trustees.

Not long ago I visited a private school where an old friend of mine was teaching. At the close of my day, I asked him "Do you know the thing about this school which has impressed me the most forcibly?" "It is, perhaps," said he, "how far behind the times we are." I had to admit that this was so. Methods were used which had been discarded in state-inspected high schools decades before.

The public school teacher works in the limelight of public knowledge. Any statement which he makes in class is reported in a hundred homes before nightfall. Any one of two hundred parents would take pleasure in reporting to the superintendent any error, even in mispronunciation, which the teacher might make. The head of a private school where I once taught, in informing me of my re-election, stated that I had maintained excellent discipline, gotten the boys to like the school and had taken part in their games and sports with enthusiasm. Here he paused, then continued: "I have not inquired as to your classroom work," said he, "but I have no doubt that it was equally successful!"

No, no one can tell me that the teaching in private schools, on the whole, is better than in the public schools, even in those "where politics holds sway."

My main plea for the public schools is based on democracy. For the good of our country it is well that young people from all strata of society should meet in a common school and learn each other's problems. Let the children of aristocrats acquire a sympathy with the struggles of the poor; let the son of the immigrant find good qualities in the scion of the old families who one day may be his boss.

Only forty per cent of the population of New England at present are descended from the old English stock. The children of the newer peoples are increasing in numbers. The children of the American Revolution can pass on to this group the splendid traditions of New England's past, but if the descendants of the Puritans insist on segregating their children in private schools from contact with the sons of the immigrants, why, so much the worse for New England. I have heard residents of certain Massachusetts cities explain that their children were not being sent to public schools because buildings were not adequate, the teachers poorly paid and the pupils an "uncultured" lot. If this is so, whose fault is it? If the so-called "best families" send their children to private schools, their only interest in the public schools is in lower costs, hence, taxes, while if these sons of the elite were going to public schools the buildings would soon become adequate, the teachers would be better paid and there might be discovered among the uncultured children of the proletariat a talent for art and an appreciation of music utterly unknown to the drab and songless ancestors of Puritan New England.

For those unfortunate children whose parents shirk the responsibility of training them for their future careers, the private school is a blessing; but the preparation which it gives, for either college or life, is not nearly as good as that accorded the boy whose parents have taken their job seriously and have given him a home environment which enables him to get his schooling in a public school where he rubs elbows with all the children of all the people.

L. P. BÉNÉZET '99

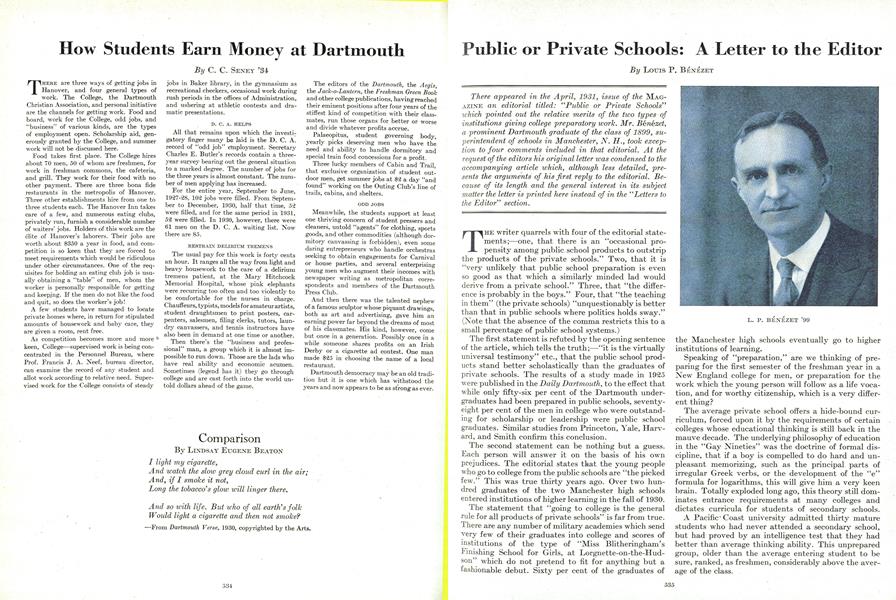

There appeared in the April, 1931, issue of the MAGAZINE an editorial titled: "Public or Private Schools"which pointed out the relative merits of the two types ofinstitutions giving college preparatory work. Mr. Benezet,a prominent Dartmouth graduate of the class of 1899, superintendent of schools in Manchester, N. H., took exception to four comments included in that editorial. At therequest of the editors his original letter was condensed to theaccompanying article which, although less detailed, presents the arguments of his first reply to the editorial. Because of its length and the general interest in its subjectmatter the letter is printed here instead of in the "Letters tothe Editor" section.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Class Notes

Class NotesCLASS OF 1929

May 1932 By Frederick William andres -

Article

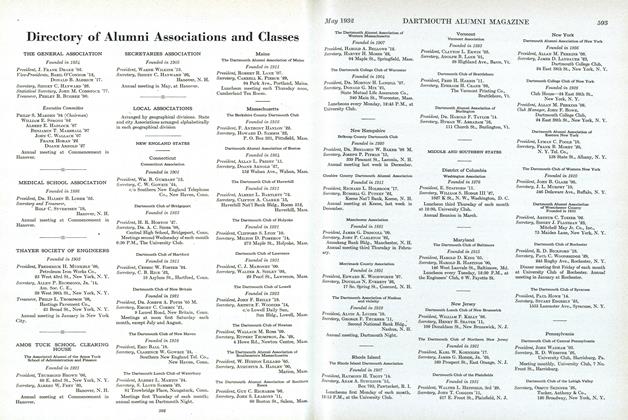

ArticleDirectory of Alumni Associations and Classes

May 1932 -

Article

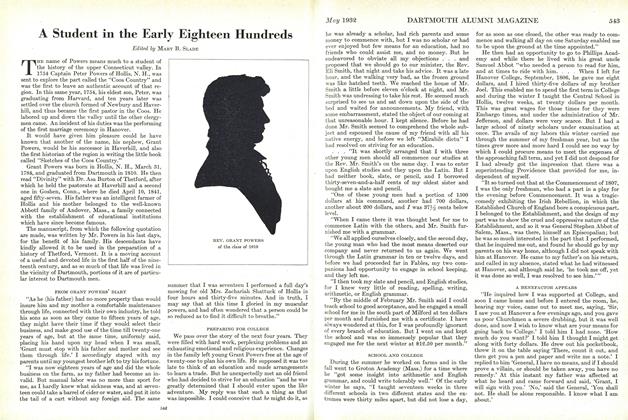

ArticleA Student in the Early Eighteen Hundreds

May 1932 By Mary B. Slade -

Class Notes

Class NotesCLASS OF 1905

May 1932 By Arthur E. McClary -

Article

ArticleLetch worth Village—A Home for Mental Defectives

May 1932 By Charles S. Little, M.D. -

Class Notes

Class NotesCLASS OF 1910

May 1932 By Harold P. Hinman

Louis P. Benezet

-

Class Notes

Class NotesClass of 1899

November, 1924 By Louis P. Benezet -

Class Notes

Class NotesClass of 1899

June 1925 By Louis P. Benezet -

Class Notes

Class NotesClass of 1899

DECEMBER 1926 By Louis P. Benezet -

Class Notes

Class NotesClass of 1899

FEBRUARY, 1928 By Louis P. Benezet -

Class Notes

Class NotesClass of 1899

AUGUST, 1928 By Louis P. Benezet -

Class Notes

Class NotesCLASS OF 1899

APRIL 1929 By Louis P. Benezet

Lettter from the Editor

-

Lettter from the Editor

Lettter from the EditorEditorial Comment

MARCH 1931 -

Lettter from the Editor

Lettter from the EditorEditorial Comment

APRIL 1932 -

Lettter from the Editor

Lettter from the EditorNew Hampshire Letter

APRIL 1932 -

Lettter from the Editor

Lettter from the EditorOn Being No. 1

MARCH 1984 By Douglas Greenwood -

Lettter from the Editor

Lettter from the EditorThe Numbers Game

JANUARY/FEBRUARY 1985 By Douglas Greenwood -

Lettter from the Editor

Lettter from the EditorYou Can't Go Home, etc.

OCTOBER 1985 By Douglas Greenwood