RESPONSIBILITY for inflicting this article on an unsuspecting Dartmouth Public is placed on the editors who for two years have been pursuing me to write an article describing Letchworth Village and its work. Now, I am perfectly willing to devote my energies to digging ditches, building roads, planning, erecting, and organizing buildings, prescribing the best kind of training for mental defectives, looking after feeding, bathing, housekeeping, and so forth, but I hate to write or talk about it. Anyone who was in College in my time well knows that I didn't carry away any prizes in literature or oratory.

In the first place, I was brought here from New Hampshire 21 years ago—much against my will and for financial reasons only—to plan a state institution for mental defectives which, when completed, would take care of 3,500 children of both sexes, all ages, and all degrees of mentality. I had, years back, a feeling that the trouble with most of our state institutions, whether prisons, hospitals for the insane, or schools for the feeble-minded, was that they were too large and that their buildings were too close together—an institution caring for human beings should be viewed from a human standpoint rather than a business one—so in planning Letchworth Village I was able to carry out my ideas, with the aid of a board of managers who generously supported me.

We took the name of Letchworth Village, first in honor of William Pryor Letchworth, who lived up in the Geneseo Valley and who devoted the most of his life to improving the conditions of the epileptic and feebleminded and insane in New York State; and secondly, we wanted to avoid any name which characterized the intelligence of the patients.

Letch worth Village is located in the Town of Haverstraw, Rockland County, New York. On the edge of the Ramapo Hills, it is forty miles up the west shore of the Hudson River and ten miles below Bear Mountain Bridge. It consists of 2,300 acres of land, of different elevations from about 400 to 1100 feet, comprised of tills, valleys, swamps, ridges, brooks and stones. The water supply is obtained from reservoirs, holding 90,000,000 gallons, in the hills above the institution.

As I have often said, the spirit of the institution is the institution, and as it is very difficult to get the right kind of a spirit in a large institution, I personally believe it is a mistake to build such. I attempted to build a series of small institutions, with possibly a different atmosphere in each, rather than to have the whole planned as one unit.

A rough classification of mental defectives places the idiot in the group with an intelligence less than that of a normal child of three years; the imbecile in the group between four and seven years; and the moron between seven and eleven; anything above that being considered borderline or possibly socially feebleminded, but not intellectually so.

With these three classifications in mind, and considering that we were building for both boys and girls, the institution was planned as six small units of about 600 each, that is:

Two units of 600 each for idiots. Two units of 600 each for imbeciles. Two units of 600 each for morons.

Each of these units to consist of: Seven or eight dormitories holding from 70 to 80 children each.

A kitchen and dining room building with a capacity for 600 or 700 children and from 50 to 75 employees, in the four groups where the children can walk to a central dining room; each cottage for the idiot has its own dining room. An employees' home to care for those working in that particular group. A school and industrial building in the two groups caring for the higher grade imbecile and moron, under 16 years of age. (We do not send to school any child who is past 16 years.) A cottage for the doctor (and his family) who has charge of that particular unit.

In carrying out our ideas of wide separation of groups and cottages, we placed the three groups for girls nearly half a mile away from the ones for boys. We placed each one of the groups—whether for boys or for girls—a quarter of a mile or so away from the next group, so that the different degrees of mentality should not mingle.

Being a crank on one-story construction for public institutions, all the dormitories are erected in this form, the walls being of field stone, but in order to carry out this program we had to advance every possible argument in favor of them and I have advanced them so many times that it has been reported that sometimes in my sleep I have talked about one-story constructionwhen all the Powers that Be are claiming that one-story construction is 40% more expensive than two-story because of the same foundation and the same roof. As a letting proposition, however, it will be found that a contractor will erect a one-story dormitory, holding from 70 to 80 children, just as cheaply as he will a twostory holding the same number. This is partially accounted for in the fact that every inch of space is utilized in one-story.construction, while in two stories or more an addition to the building is made in order to obtain room for the stairway, and construction becomes more expensive as you go up in the air. The main idea in one-story construction is that there are no dark corners; every child gets out of doors—in fact they can not be kept indoors—and the building can be supervised enough cheaper to pay for its cost in less than fifty years.

Every dormitory in a group is separated from the next by from 200 to 400 feet, so as to provide ample playground space for the children of the building, with a large central playground which can be used for holidays, Saturday afternoons, Sundays, at cetera.

The institution was planned with some idea of architectural effect, adopting the Jeffersonian home type of architecture for each building (Jefferson's ideas of architecture are the only ones of his that I ever did approve of) with the hope that after a period of years when the grounds were filled with trees and shrubs, one might pass through the locality without realizing that it was a public institution and to avoid what we often see, three- or four-story buildings upon a hill which from their appearance stamp them as a public institution.

Now in regard to things that we do for our children. The larger part of them come to us from Greater New York, and with names, for the most part, that read like those of the modern football team—unpronounceable. Within a week after their admission they have physical, psychological, and school tests; they are immunized against diphtheria, typhoid fever and small pox, and Wassermann tests are made. Then they are perma nently assigned to the cottage in which they best fit. I they are under 16 years of age and mentally above fou years, they go to one of the two schools which we main tain—one for boys and one for girls. In the school there are classes of children ranging from kindergartei to possibly the fifth grade—rarely is there a child in th institution who can do above fifth-grade work. Th value of schoolroom work is a much discussed question but I argue that I spent four pleasant years in Dart mouth and it must have done something for me, a otherwise I would still be driving an ox team among the rocks of Webster, New Hampshire.

One-half of each day is devoted to scholastic work and the other half to hand and industrial work, or to gym nasties and music. We have singing classes, a boys band, a girls' orchestra, as well as a school library when the children may go to select picture books or simple interesting reading books.

All of the children, as we call them—as they an children, mentally—over 16 years of age and who an physically able, are placed at some practical outdoor o indoor work, depending where they will fit best. Thi girls, on the other hand, classed in this group, are in ou sewing rooms, laundry, kitchens and dining rooms employees' buildings, or industrial classes. There is ; large number of very low-grade children who perhap, have to be fed, bathed, and cared for like the younges child as long as they live.

As far as I know, the higher grade type of mentalb defective lives just as long as anyone else, but it is ran that we see a low-grade child above the age of 25. The; have slight resistance and succumb to influenza, measles tuberculosis, at cetera.

I am asked to describe a day's work. To begin with the milking group goes to the cow barn at 3:30 a.m., thi teamsters are out at 5:00; children who work in kitch ens and dining rooms report to those buildings at 6:00 Breakfast for everyone is at 7:00. After that the schoo children return to their cottages to get ready for the da;; in school. All others who are physically able to do any thing are placed at work indoors or out, under super vision, the boys at farming, road building, clearing land shoveling coal, at cetera; and the girls in the kitchens, dining rooms, sewing rooms, laundry, at industrial work, or possibly out on the land during some of the seasons.

In managing children—and possibly anyone else—it ought to be a combination of work and play, so while they work regularly between the hours of 7:30 and 11:30 in the morning and 12:30 and 5:00 in the afternoon, Saturday afternoons and Sundays (outside of the Church Services) are given up to more or less organized play. During summer evenings there are all kinds of out-door baseball games, basketball, 'soccer, croquet, swimming, caring for individual gardens, etc., and in the winterbesides the entertainments which are held in the individual cottages—there is a weekly dance and movies. Movies, in my opinion, were very largely made for the entertainment of the feeble-minded.

Everyone is in bed at 9:00 o'clock, excepting two evenings a week that are given up to diversions outside of their own buildings.

On Sundays Catholic, Protestant, and Jewish services are held during the forenoon by outside clergymen. The rest of the day is given up to visitors and to sports.

Now, as to what becomes of them after they are once admitted here. The law states that they shall remain at the discretion of the managers of the institution but, practically, you can not keep the high-grade feebleminded in an institution unless it is maintained as a prison, and as we have always maintained that we were running an institution for children, with only unlocked doors and fly screens in the windows, it is perfectly easy for children to run away at any time if they want to. Most of our runaways are picked up and returned to the institution. Every year a certain number leave and never return. What we would like to do with all the high-grade cases is to place them out on parole after they have been trained in the institution and we feel that they have at least a gambling chance of getting on. The question as to whether or not they get on depends not so much upon their ability to do good work—for almost any feeble-minded person can be taught to do good work—as on their personality.

We are inclined to speak of the good and the bad feeble-minded. The good being the more or less honest, industrious type, while the bad feeble-minded are the lying, thieving, lazy, difficult cases to get on with.

So we maintain a parole system. Most of our girls go into domestic work and most of our boys are employed on farms, as that is the work they are best fitted for. Drawing, as we do, a large part of our population from the foreign-born, the families are very insistent on getting hold of their children when they are past the school age and can work, and placing them where they will be able to bring something into the home. If they do not get them out of the institution one way they do it another, so these children are constantly returning to the communities—a considerable number of whom should never go back.

The lower grade, however, remain in the institution as long as they live unless the conditions of the family so improve that they are able to take care of the children themselves.

As the higher grades are the only social problem it seems unfortunate that with this group (with a bad heredity and the almost certainty of transmitting future generations of probable feeble-minded individuals, at least poor citizens) we haven't a sterilization law which would permit us to sterilize this group before it leaves the care of the state.

There is still a great argument in regard to the importance of heredity and we know perfectly well that high-grade feeble-minded cases appear in perfectly normal families, but any experience that I have had shows that at least 60% of the higher grade cases have a defective family history. The low grade cases, on the other hand, almost always have a good family history, the cause being due to accidents of childbirth, serious illnesses, or injuries.

Letchworth Village really consists of three parts: Home, School and Laboratory. The Home Department makes for the care of the children and attempts to make that home as near like the normal home as possible, but it is difficult where large numbers are congregated under one roof. Consequently, a great deal of attention is given to the housekeeping, diet, cleanliness, personal appearance, play, and diversions.

The School Department is more or less as I have described it, although we consider everyone in an institution, a teacher whether in the school building, laundry, kitchen, or on the farm. I have often said that if I could have but one implement with which to educate a feeble-minded boy, I would take the grub hoe.

The establishing of habits of industry by regular work from breakfast to supper time, and regular hours for meals, play, going to bed, and so forth, is highly important. Even the very low-grade child with a mentality of less than three years can be taught to do one thing exceedingly well.

The Laboratory Department consists of a medical director, a pathologist, psychologists, social workers, and technicians. We hardly expect to solve any large part of the problem of the cause of mental defect, but we would at least like to leave behind us a complete record of what mental defect is, as we see it, so that if we do not accomplish anything, someone in the future will be able to take our records and give to the world something of importance. Personally, I am very doubtful about making any large contribution to the knowledge of mental deficiency, but I do hope we have made a contribution which may be utilized by all kinds of institutions as to how an institution should be planned, built, and organized.

The accompanying photographs may give an idea of some of the things mentioned here. I will close by saying that to be really happy you should be a little feebleminded.

KINDERGARTEN BAND

BOYS' INDUSTRIAL CLASS

GIRLS' ORCHESTRA

DR. LITTLE, a graduate of the College in the class of 1891 and of theMedical School in 1895, enjoys the uniquedistinction of having played six years ofvarsity football at Dartmouth. "Squash"Little as a rusher, guard, and tackle was abulwark, in every sense of the word, of theBig Green rush line in the early days offootball on the campus. He was captain ofthe 1894 team, during his days as a MedicalSchool student. As the founder of Letchworth Village andits constant guide and director for 21 yearsDr. Little has made a distinctive contribution to the medical profession. A recentreport of the board of visitors of the schoolsays: "From small beginnings LetchworthVillage has grown to its present size. It hasblazed new trails and set new standards.Many of the ideas which were in advance ofpublic opinion twenty years ago are nowaccepted generally . . . Dr. Little hasmade Letchworth Village what it is today."

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Class Notes

Class NotesCLASS OF 1929

May 1932 By Frederick William andres -

Article

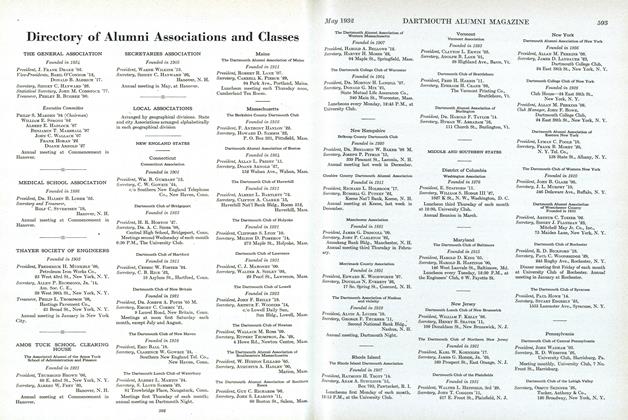

ArticleDirectory of Alumni Associations and Classes

May 1932 -

Lettter from the Editor

Lettter from the EditorPublic or Private Schools: A Letter to the Editor

May 1932 By Louis P. Benezet -

Article

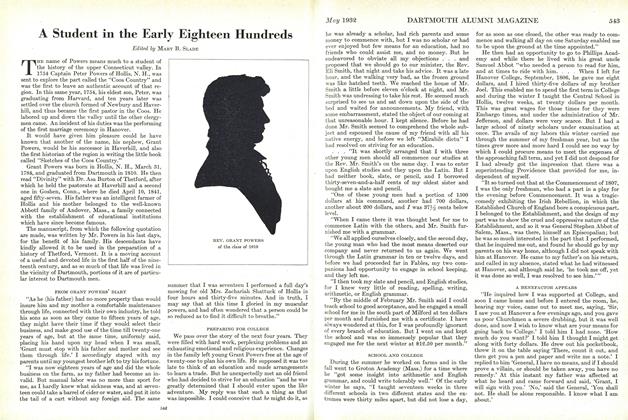

ArticleA Student in the Early Eighteen Hundreds

May 1932 By Mary B. Slade -

Class Notes

Class NotesCLASS OF 1905

May 1932 By Arthur E. McClary -

Class Notes

Class NotesCLASS OF 1910

May 1932 By Harold P. Hinman