IN a recent article in the Atlantic, Mr. John R. Tunis, the well-known sports writer, considers in a stimulating way the underlying motive in American sport—the placing of victory above all else, or above nearly all else.

Three degrees of latitude will reverse all jurisprudence and there seems to be a very similar virtue in meridians of longitude. Speaking broadly, the great difference between the views taken by Englishmen and Americans of the whole matter of sport relates to their notions of how important it is to win a game. One British writer sums it up by saying in effect that Americans lay too much stress on victory, and Englishmen too much on being good sportsmen. The competitive spirit, which is what makes games in the first place, certainly dictates in each instance that one should desire to win rather than lose. The whole idea is a trial of strength and prowess, into which one goes with the hope of succeeding. But to just what extent should competition be the life of sport? Just how hard should one play? It is possible that excessive competition is the death of sport, as it is the death of trade.

No one defends the winning of victories by resort to trickery. One finds instances of it now and then, but it would be generally agreed by all decent Americans that victory won by such means would be barren. The great differences relate to the employment of strategy—the taking out and sending in of fresh players to meet special emergencies in a baseball or football game. There is also a fundamental difference between British and Americans as to the essential desirability of victory. It is plausible to say that if a game is worth playing at all it is worth winning—and also plausible to say that after all it is -only another game, and that the loser may conceivably survive the night despite his momentary disappointment. Instances are cited to make the difference clear. An Englishman will forego an advantage which would shorten a game and give him a victory on his opponent's errors, because to shorten the game thus would deprive him of the healthful exercise he covets. An American will take any chance to shorten the contest and win through the mistakes of his adversary because what he wants isn't exercise so much as victory.

Quite probably the passion of each race for its chosen ideal is exaggerated. There may be room for salutary changes of view on both sides. There seems to be little doubt that we, over here, incline to overrate the importance of victory, and that they, over there, underrate it. But what is to be done about it? These varying estimates arise out of national character and are spontaneous enough. Very few would deny that the desire for victory could be overemphasized and that there are things much worse than defeat.

A good beginning has been made in the eradication of what was perhaps the worst consequence of the victorypassion—the covert hiring of players to win games for college teams that would lose if dependent on bona fide talent. That is the glaring instance in which excessive devotion to the victory complex has led to trouble. It has taken a surprisingly long time and a discreditable amount of effort to awaken people to the knowledge that a successful team of hired players brings only an imitation glory. That it did take so much time and effort undoubtedly affords the most cogent proof that the desire for winning is commonly overworked in this country.

It is less easy to prove that the indifference to results of a game is overdone in England. Nevertheless we incline to believe that it is, and that the ideal conditions require a change in the general attitude of the young men of both countries. There is no glory in winning a game by the sacrifice of true sportsmanship—but there may be no glory in losing a game when it could be won without forfeiture of true sportsmanship. After all, if we didn't hope to win we shouldn't play any games at all.

One difficulty lies in the differing postulates as to what good sportsmanship demands. The American cannot see that it is poor sportsmanship to make substitutions for strategic reasons, while the Englishman insists that it is. You ought, he says, to substitute no player save in the case of an injury. If you can't win with the team you send in at the start, just lose the game and charge it up to the fortune of war. To reconcile these opposing notions is hardly possible—and as a result each nation will probably go on as it is, feeding its athletic soul with the food convenient for it.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Class Notes

Class NotesCLASS OF 1929

May 1932 By Frederick William andres -

Article

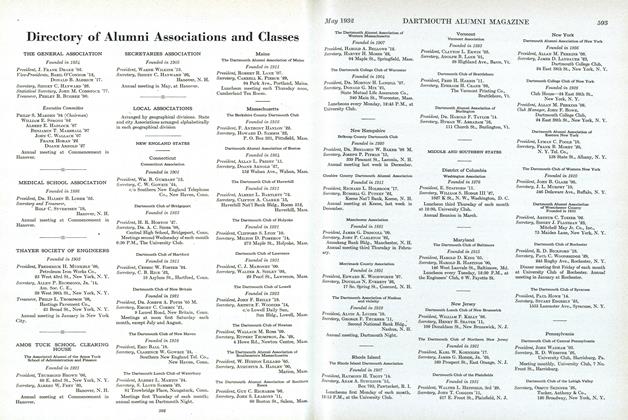

ArticleDirectory of Alumni Associations and Classes

May 1932 -

Lettter from the Editor

Lettter from the EditorPublic or Private Schools: A Letter to the Editor

May 1932 By Louis P. Benezet -

Article

ArticleA Student in the Early Eighteen Hundreds

May 1932 By Mary B. Slade -

Class Notes

Class NotesCLASS OF 1905

May 1932 By Arthur E. McClary -

Article

ArticleLetch worth Village—A Home for Mental Defectives

May 1932 By Charles S. Little, M.D.

Article

-

Article

ArticleAfter a highly uncertain and unsatisfactory

December 1916 -

Article

ArticlePRESIDENT HOPKINS' ENGAGEMENTS

February 1920 -

Article

ArticleTHE CLASS OF 1918 GATHERS FOR ITS ANNUAL POMONOK OUTING RECENTLY IN NEW YORK

November 1946 -

Article

Article1954-55 Schedule of Alumni And Other Weekend Dates

November 1954 -

Article

ArticleCancer Clinician

JUNE 1967 -

Article

ArticleProfessor Adams

October 1938 By Royal Case Nemiah