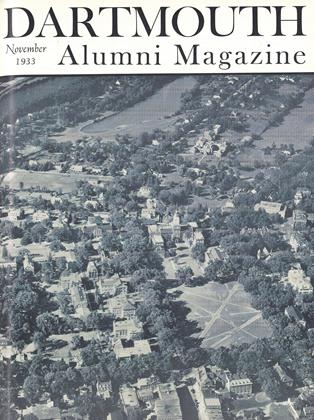

ROBINSON HALL, home of non-athletic student activities, has been well nigh choked with smoke, and but little damaged by fire, since last we went to press. The undergraduate publications, suddenly confronted with the problem of a changing college, editorialized themselves into a Freshman Rules, incipient football hysteria, campus cynicism, and the like.

Bubbling merrily in its own little teapot, Editor Danzig's Dartmouth veered about-face on its policy of last May, declared that Freshman Rules were "a form of mob hysteria," giving "a permanent false impression" of the College, and campaigned lustily (for three whole days) for their abolition. The opinion of the freshman class was decidedly in favor of the rules, upon examination; Palaeopitus voted eleven-to-one against abolition; and along came Delta Alpha and the whole matter now looks hermetically closed.

Steeplejack, Dartmouth's new "journal of controversy and opinion," next took up the torch in the Good Fight against the "new spirit" by vaguely attacking the rahrah components thereof in its first issue. Finding itself charged with "slacker cynicism," Steeplejack cleared the air with an admirable attack on cynicism itself. Editor Strauss logically demanded the right of criticism at Dartmouth, protested against "over-innocent loyalty." The journal now stands committed to rationalism and a loyalty to the College based on intelligent understanding.

Peculiarly enough, the excitement confined itself largely to Robinson Hall and its staffs. The campus was never quite sure what the keen young men were fighting about; and, quite characteristically, cared very little in any event. The day is not far off, we are sure, when the editors—sincere, well-meaning and intelligent as they arewill discover that at times they have been attacking straw-men they have themselves set up. The "campus," just like the equally intangible "masses," still considers hysteria, cynicism and rationality to be vague, rather inconsequential words.

CROWLEY ONCE AGAIN

But the boys of late are seeing beyond their noses and out of all the dither some few flames of importance have raised their interesting heads. The editors and others of comparable intelligence are realizing the basis for all their excitement and fears: there is something wrong with the college.

This is one of the few matters on which it is possible to gather anything resembling a unanimous "campus opinion." The feeling that the present Dartmouth set-up is not wholly perfect ranges from the belief that the college is spiritually bankrupt to a subconscious suspicion that something's missing around here. And we have seen tacit admission of this truth in the colorsupplying Rules, rallies, and stimulated "spontaneous enthusiasm."

With the dogmatism of the undergraduate we assert that this is all .one way or another of stating that the classroom has failed. Education, because of faulty or incomplete correlation with outside life, has proved too uninteresting to claim a major portion of student thought or time. The Dartmouth is now running editorial after editorial calling for the abolition of prerequisites, for the integration of the social sciences, for a course in Marriage and one in Modern Literature (which latter, it was later discovered, has been taught in Dartmouth for the last fifteen years); and Steeplejack likewise—although in a more far-sighted manner—has been crusading for the Ideal College, claiming that while Dartmouth may be the best large institution in the country, it isn't good enough.

We suspect somehow, that the Administration knows all this, since Dean Bill has been assigned to the work of changing the curriculum. In time we will be graced with a course of study more in keeping with a revolutionized America. The chief ground for undergraduate criticism is merely that Dartmouth, along with thousands of other colleges, has been caught short by the Depression. Only since financial worries have been assailing the average student has he taken cognizance of the outside world at all and demanded a more modern education; and only since the Depression has "change" in Dartmouth's curriculum seemed emphatic "necessity."

LET'S GET TOGETHER

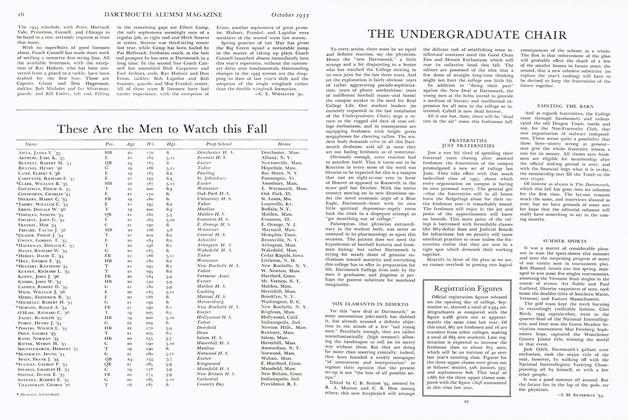

For the first time in many long years, Dartmouth staged a rally before a minor football game. To the fanfare of the College Band, some thousand students assembled in Webster Hall the evening before the meeting with Bates. At last, opined the cynics, football hysteria was having its day and Dartmouth was entering the Era of Hotcha.

We are pleased to announce that both the sour young men and the do-or-die boys were wrong. The rally, conducted by Coach Holbrook '20 and the ineffectual cheerleaders (who don't yet know quite what to do with their hands), was never allowed to get out of bounds. The boys sang and cheered, were addressed very quietly on the subject of "spirit" by Coach Cannell '19—who refused to get himself or the crowd excited—and enjoyed themselves immensely.

The freshmen, warmed by the speeches into whole-hearted enthusiasm for the team, then crossed the campus and proceeded to storm The Nugget. A large portion of the varsity, however, turned out to be members of Paiaeopitus, staunch defenders of The Nugget. The freshmen, confronted with this problem, attempted to enter without damaging the defenders. The white-hats had no such qualms, and repelled the youngsters effectively for a time. Eventually, sheer poundage wonand the invaders burst through the doors, victory on their cheery faces. The everresourceful Nugget, however, unleashed a few tear-gas missiles, and the crowd dispersed, proving modern science (which has also invented machine guns) to be a wonderful thing.

Dartmouth recently staged another rally of a completely different nature. Minus the hoopla of a Dartmouth build-up and bandmusic, a section of the College, three hundred strong, assembled at the Claremont airport at eleven o'clock on the night of October 16. They had been asked to come down, at a few minutes notice, to light up the landing field with their automobile headlights for the landing of an airplane. Seventy-five automobiles waited at the airport over an hour for the arrival of a Rochester physician who was to operate on a critically injured sophomore.

There was no question of coming or not coming, if it was possible to get away that night. They traveled thirty-odd miles and would have gone farther if necessary. They "got together" naturally, spontaneously, in the old-fashioned way Dartmouth men can be truly proud of.

FRATERNITIES—OR FRATERNITIES?

The Non-Fraternity Club adopted the name of "The Bema," campaigned for members, arranged for a Fall House Party Dance and entered into interfraternity athletics. The Interfraternity Council, which had not been informed of the Intramural Council's action placing The Bema in competition with the fraternities, waxed a bit impetuous and decided—rather logically—not to award Interfraternity Cups to non-fraternity organizations, and not to meet non-fraternity organizations in interfraternity competition.

The Dartmouth hopped on this technical point, regarding it as a move of reprisal, and editorialized that the Administration would like to see fraternities dead anyway. The Administration—in the person of President Hopkins—denied this statement of The Dartmouth, and censured the Interfraternity Council's move. The president of the Interfraternity Council explained the situation and agreed that the decision had been hasty. The Bema withdrew from the Interfraternity League.

In passing, any belief that the incident developed wholly from fear of The Bema's potential power does not seem particularly intelligent in view of the fact that the fraternities pledged four hundred and thirty men from the class of 1936. Obviously enough, however, club organizations on the campus must loom as a threat to the smaller houses in time, and without doubt, some fraternities voted with this in view. In any case, the situation is not of great moment at the present time. Five years from now, however, the campus may be studded with a dozen clubs of The Bema variety, and the fraternity houses may be serving as college dormitories; and the fraternities—who can tell?—may be doing their bit to prevent this state of affairs.

SOMETHING DOING EVERY MINUTE

Green Key reinstituted Freshman Placards (a poor cartoon abetted by some terrible verse) at thirty-five cents the placard .... The freshmen were "advised" to purchase. . . . The undergraduates as a whole are fairly optimistic about the football team. . . . "We're going to beat Yale this year". . . . The sophomores pulled the brightest trick in years by placing five sprinters on their front line in the class rush. . . . They secured four balls within sixty seconds. . . . Amelia Earhart went over in a large way when she addressed the campus during a recent chapel-period

. . . . Said Amelia: "Traveling on a train a few days ago a conductor stared at me, saying he had seen my picture in the papers but couldn't place me. 'Ah, now I have it' said he, 'you are Mrs. Roosevelt'!" .... Palaeopitus reopened its automobile-safetydrive. . . . One of its most helpful contributions to the student body. . . ."MerryGo-Round," the daily's humor column, is as nauseatingly squirrelish as ever at times .... Funniest writing of the year was the daily's parody of Roald Morton's "Diary" in the first Steeplejack. . . . Dartmouth now has a polo team, with its own field and everything—including a one-goal man. . . . The freshmen are wearing gabardine and glenurquhart; we play polo; Campion's and the Co-op are cleaning up on full dress outfits. . . . And people are still talking about "getting away from sophistication."

. you are Mrs. Roosevelt!"

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Sports

SportsFOLLOWING THE BIG GREEN TEAMS

November 1933 By C. E. Widmayer '30 -

Article

ArticleHANOVER BROWSING

November 1933 By Rees H. Bowen -

Class Notes

Class NotesClass of 1930

November 1933 By Albert I. Dickerson -

Article

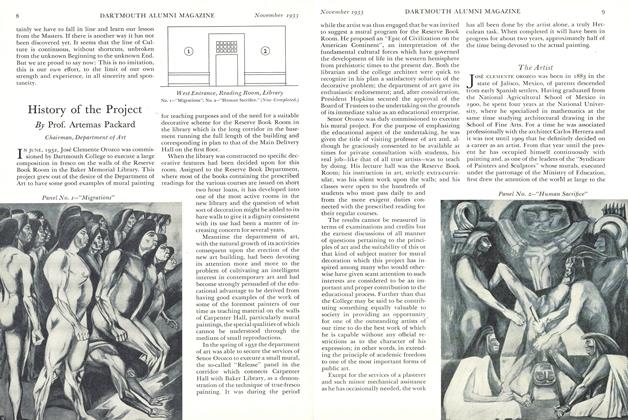

ArticleHistory of the Project

November 1933 By Prof. Artemas Packard -

Class Notes

Class NotesClass of 1910

November 1933 By Harold P. Hinman -

Class Notes

Class NotesClass of 1908

November 1933 By Laurence W. Griswold

S. H. Silverman '34

-

Article

ArticleTHE UNDERGRADUATE CHAIR

June 1933 By S. H. Silverman '34 -

Article

ArticleTHE UNDERGRADUATE CHAIR

October 1933 By S. H. Silverman '34 -

Article

ArticleEASY DOES IT

By S. H. Silverman '34 -

Article

ArticleDEATH AND DARTMOUTH

April 1934 By S. H. Silverman '34 -

Article

ArticleTHE GREAT AWAKENING

April 1934 By S. H. Silverman '34 -

Article

ArticleTHE OTHER SIDE

April 1934 By S. H. Silverman '34