DURING THE inauguration of President Nichols in 1909 a dinner was given in Hanover at which were present some of the most distinguished men in American education. The speakers that evening were, among others, James Bryce, President Lowell of Harvard, Former President Angell of Yale, President Schurman of Cornell, President Hyde of Bowdoin, President Emeritus Eliot of Harvard, and President Woodrow Wilson of Princeton. It was one of the most notable gatherings in the history of the College, and as well of the educational world. One period in education was at that time closing, another beginning, and it was the speaker mentioned last on this list who broke most definitely with the past.

Woodrow Wilson, at that time in the closing years of his administration at Princeton, had this to say: "I was confessing to President Schurman tonight that as I looked back to my experience in the classroom of many eminent masters I remembered very little that I had brought away. The contacts of knowledge are not vital; the contacts of information are barren. If I tell you too many things that you don't know I merely make myself hateful to you. If I am constantly in the attitude towards you of instructing you, you may regard me as a very well informed and superior person but you have no affection for me whatever." The whole purport of this extraordinary speech by Mr. Wilson seemed to be that the college of his day, with its more or less conventional processes had left the student untouched, unstirred, unenlightened.

To make studies more available for instruction there have developed, in increasing degree, divisions of faculty and students into groups and classes and departments. The departments were more or less ironclad in the beginning, and they successfully repulsed the encroachments made by demands for new departments and wider spread of old departments. Toward the end of the Twentieth Century new subjects began to creep in, Sociology, later Comparative Literature, Psychology,—scattering groups such as Evolution and Citizenship, until today the creation of new departments is met with scarcely any opposition. To keep the students' efforts in the liberal college broader, a group system was at first devised, after the battle for free electives had been won, whereby the student could select the department in which he did his principal work in the latter two years of college, without neglecting some work in other departments. The departmental work was rather stiff and insured a program, of thoroughness, with special, and later, comprehensive examinations.

But the student was beginning to make himself heard. Indeed when the curriculum first showed signs of change, the student began to struggle for courses which gave him the most benefit and intellectual pleasure. This struggle is still going on. It may in the long run determine the future of the academic curriculum. The student objected to certain "majors" which he had elected in good faith but which turned out to be different from his expectations; but, by the end of a year, he had nothing else to do but to follow his first choice, now seen to be an error. The student saw in the catalog certain courses listed which appeared to him to be desirable, but he was unable to take those courses because he lacked the necessary "prerequisites." The drudgery of an unwelcomed major casts its shadow over a whole college career.

And the teacher has his side too. Few people realize how much work and effort and constant priming is necessary for a teacher to come before a group once or twice or three times a week and discuss the subject in question or conduct student discussions and yet keep himself enthusiastic and interested. After all, must a course be given on three days a week? The course may be laid out as a lane leading to some comprehensive examination and the sub- ject matter may be a simple matter of routine; in such a case it is likely to become deadly, when given three times a week, unless the instructor can constantly freshen both himself and the subject with new and living material. The instructor must also deal with an uninterested group in his class; there is usually such a group. The most astute kind of salesmanship is necessary to reach these students. Outside of class the instructor must keep himself posted on all the changes that are constantly happening in his field, and this work, in some subjects, involves much time and energy.

The world does not stand still, the subjects one teaches are constantly changing; why then, in all consideration, should the methods of creating interest in them stand still? No one generation of college men is ever contented with the material that is gained in college, nor with the method, by which the ends that the college seeks, are gained. Dartmouth has been notable since the incoming of the present administration in 1916 for its efforts in trying to make its teachings more effective. Nothing spectacular nor extremely radical has ever been attempted, yet there has been original thinking and action in Hanover in terms of the liberal curriculum which seems only to meet the needs of the time for which it is devised.

The liberal college still stands for that for which it has always stood, for the cultivation of good taste, health of mind and body, the development of intellectual enthusiasms, the stimulation of an appreciative and critical spirit for what men have done in the past for the good of the world, and the desire to apply methods of thought to the present day world. In view of the changes and embroilments of the past, the effort and struggle in every decade to bring curriculum methods up to a point where they will be effective in an ever changing world, Dartmouth is meeting the issue by the appointment of a Dean of the Faculty whose work will include this matter of curriculum adjustment and change. It is one of the most needed additions to the administrative functions of the College if colleges are to meet the demands of the age. The curriculum, which includes the subjects that are taught, the divisions of teaching staffs for presenting the subjects, and the methods by which the teaching is imparted and regulated and made effective, in its ideal form, is a thing of growth. It changes constantly from year to year. If, as in the case of an Utopian government, the curriculum could be sensitive enough to modify itself with any perceptible demand, there would be no need for drastic change at any one time.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Article

ArticleHANOVER BROWSING

December 1933 By Rees H. Bowen -

Class Notes

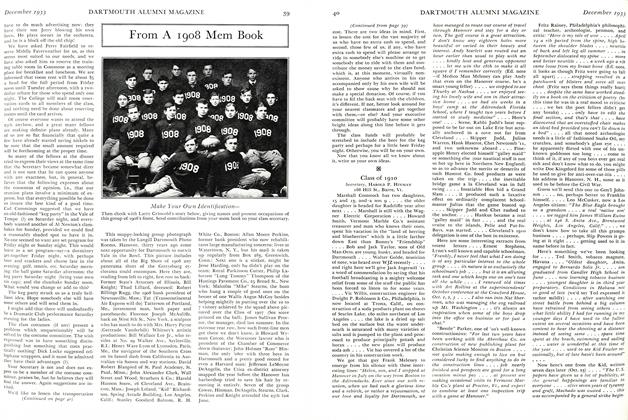

Class NotesClass of 1910

December 1933 By Harold P. Hinman -

Class Notes

Class NotesClass of 1930

December 1933 By Albert I. Dickerson -

Sports

SportsFOLLOWING THE BIG GREEN TEAMS

December 1933 By C. E. Widmayer '30 -

Class Notes

Class NotesClass of 1929

December 1933 By F. William Andres, Gus Wiedenmayer -

Article

ArticleENGINEERING, A WAY OF LIFE

December 1933 By Arthur G. Tozzer '02

Article

-

Article

ArticleStudent Fees Raised

May 1949 -

Article

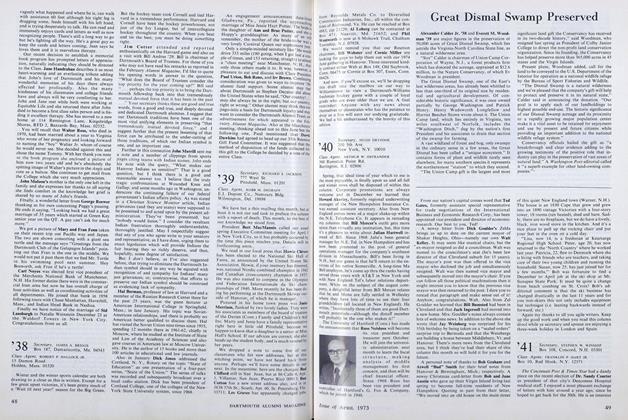

ArticleGreat Dismal Swamp Preserved

APRIL 1973 -

Article

ArticleMasthead

NOVEMBER • 1985 -

Article

ArticleIt's Just Like Talking to People

APRIL 1984 By Debbie Schupack '84 -

Article

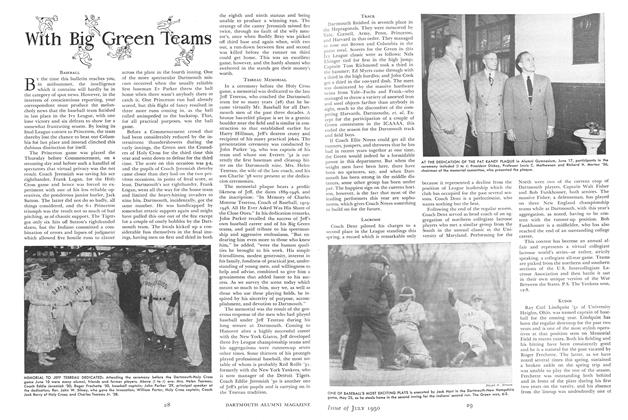

ArticleLACROSSE

July 1950 By Francis E. Merrill '26 -

Article

ArticleSputnik, Lost Moons, And Spacefarers

March 1996 By Proffessor Mary Hudson