WITH CHARACTERISTIC thoroughness, The Dartmouth of March 12, 1909, reports that "the Jack-o-Lantern appeared yesterday morning at Chapel and Hanover newsboys spent ten busy minutes dispensing the sheet to men. The interest aroused was general and the satisfaction in the present number seemed to forecast the popularity of the paper." It was twenty-five years ago this month then that W. T. Atwood '09 and J. Howard Randerson '09 dispatched the first issue of "the comic monthly of Dartmouth College" to its printer, who (it must be confessed) was not completely bowled over by his twenty-page assignment.

But this year of banking crises and unemployment seems no fitting time to be shouting hosannas because a comic magazine has reached its twentyfifth birthday. What may occasion surprise, however, is that any magazine, regarded by its kindest critics as a luxury, has existed for so many years at a college where at least five periodicals have perished in the same period.

An answer to this hypothetical question involves analysis o£ such perplexing words as "comic" and "luxury." To its long line of editors, the first has always meant a playing of wit over the sacred cows of Dartmouth students—over its contemporary, TheDartmouth, "which gets a laugh every day," over senior societies, fraternities, grades, athletics and all the dubiously worth while items the college man sometimes magnifies to fallacious significance. And to twenty-five classes of Dartmouth students this humorously critical "voice in protest," to quote Charles Kingsley, editor in 1914, "against . . .

cant, hypocrisy, braggadocio, blindness, hide-bound conservatism," was apparently important enough to lift Jack-o-Lantern out of the "luxury" class (with its implications of worthlessness) into the sphere of comparative necessity.

Jacko has survived, moreover, for reasons that perhaps Dartmouth men alone will understand. One of the unique features of this college has been its tremendous vitality, energy and faith which have raised a small New England school to a ranking position in the educational world. The undergraduate scanning the files finds this liveliness strongly reflected in the pages of his comic magazine. To many present-day readers, the lusty spirit in which Jacko-Lantern attacked compulsory chapel, dance-fads and fellow-publications will no doubt seem puerile; but a similar spirit was the creative force behind that Dartmouth legend which is one of the dearest possessions of every living graduate; and it gave Jack-o-Lantern its own justification for existence. And if the "wanton page" of the magazine at times offended against the strictest canons of good taste, those respecting vitality and growth were able to forgive occasional excess.

In common justice it cannot be supposed that Jacko always kept the faith. It too, along with the pack, jested at the idea of woman suffrage; and for a time it caught the Jazz-Age fever it was assailing. Occasionally it has been hysterical and esoteric. Yet at other times it has maintained its perspective when most others were bleating like sheep: from 1915 to 1917 Jack-o-Lantern launched intelligent criticism at the World War. . . .

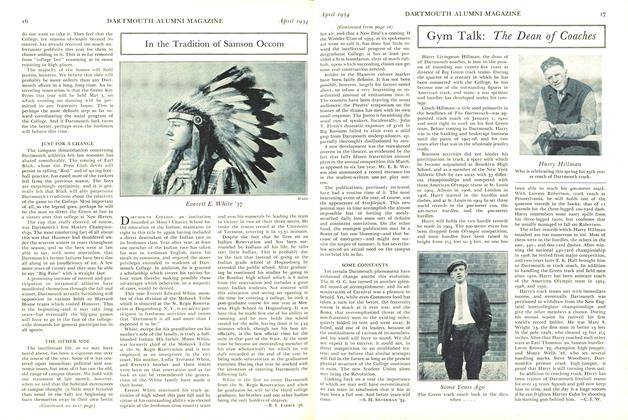

But almost always it has held fast, with minor digressions, to the guiding principle of any college comic—that of reminding an over-serious or overflippant student body to laugh at its own pretensions. Apparently this work has reaped dividends for the men who set themselves to this task: Walter Beach Humphrey, Harrison B. McCleary, Gene Markey, Walter F. Wanger, Stanley Jones, Alexander Laing, Jim Taylor, Dr. Seuss, Clifford Orr and Abner Epstein were all of the pumpkin's fellowship.

Jack-o-Lantern to-day is attempting to carry on the tradition the preceding years have handed down —vitality, evolution, intelligent laughter at stupidity and lack of perspective. In addition, the magazine is motivated with a "new" purpose—that of furnishing the College, in a novel, artistic format, with "an organ of collegiate opinion." At this "new" purpose the old, old Jacko must smile somewhat tolerantly: the editorial column of the magazine for October, 1909, reads in part: "The threefold mission of the J ack-o-Lantern, then, is to be funny, to be representative of the best undergraduate opinion, and to be a work of art."

Editor, Dartmouth Jack-o-Lantern

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Article

ArticleDARTMOUTH MEN IN AVIATION

April 1933 By Carroll A. Boynton '33 -

Class Notes

Class NotesClass of 1910

April 1933 By Harold P. Hinman -

Article

ArticleHANOVER BROWSING

April 1933 By Rees Higgs Bowen -

Article

ArticleNorthern April PART ONE

April 1933 -

Class Notes

Class NotesClass of 1902

April 1933 By Hermon W. Farwell -

Article

ArticleTHE UNDERGRADUATE CHAIR

April 1933 By J. S. Monacan'33.

S. H. Silverman '34

-

Article

ArticleArtist, Designer, Caricaturist

May 1934 By Abner Dean '31, S. H. Silverman '34 -

Article

ArticleTHE PROBLEM REMAINS

By S. H. Silverman '34 -

Article

ArticleLUCKY '37!

By S. H. Silverman '34 -

Article

ArticleTHE GREAT AWAKENING

April 1934 By S. H. Silverman '34 -

Article

ArticleJUST FOR A CHANGE

April 1934 By S. H. Silverman '34 -

Article

ArticleSOME CONSTANTS

April 1934 By S. H. Silverman '34