WITHOUT DETRACTING in the least from the centennial honors that are being accorded the inventor of the magnetic telegraph, the fact should not be forgotten that the pioneer telegrapher in civilized America was Jonathan Grout Jr., a graduate of Dartmouth College in the class of 1787. His remarkable achievement in the first years of the 19th century in transmitting messages in a few minutes across a hundred miles of land and sea, which under ordinary circumstances required days to deliver, has never been justly estimated nor adequately recorded.

In order to appreciate the magnitude of Grout's task, the success of which must now be regarded as one of the outstanding events in the early history of the country, it should be remembered that at the time when he drove his line through the wilderness of Plymouth and Barnstable counties, long-distance travel was confined to coasting along the shore in small sailing vessels, or jogging along winding paths on horseback, for land journeys by any kind of a wheel vehicle were impossible beyond a few miles from the centers of population. News necessarily was slow in spreading, and important events were days in becoming generally known. Salem did not learn of the death of Washington until nearly two weeks after it had taken place.

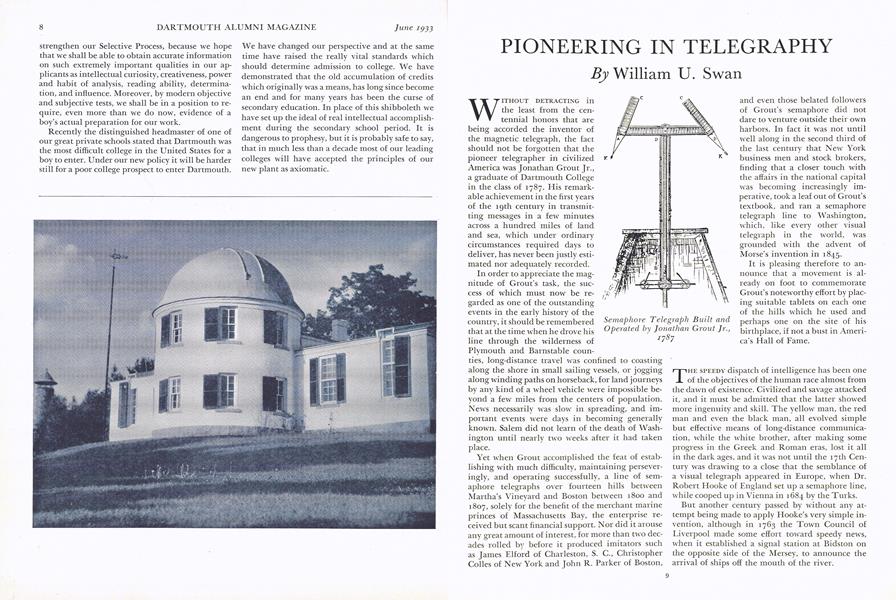

Yet when Grout accomplished the feat of establishing with much difficulty, maintaining perseveringly, and operating successfully, a line of semaphore telegraphs over fourteen hills between Martha's Vineyard and Boston between 1800 and 1807, solely for the benefit of the merchant marine princes of Massachusetts Bay, the enterprise received but scant financial support. Nor did it arouse any great amount of interest, for more than two decades rolled by before it produced imitators such as James Elford of Charleston, S. C., Christopher Colles of New York and John R. Parker of Boston, and even those belated followers of Grout's semaphore did not dare to venture outside their own harbors. In fact it was not until well along in the second third of the last century that New York business men and stock brokers, finding that a closer touch with the affairs in the national capital was becoming increasingly imperative, took a leaf out of Grout's textbook, and ran a semaphore telegraph line to Washington, which, like every other visual telegraph in the world, was grounded with the advent of Morse's invention in 1845.

It is pleasing therefore to announce that a movement is already on foot to commemorate Grout's noteworthy effort by placing suitable tablets on each one of the hills which he used and perhaps one on the site of his birthplace, if not a bust in America's Hall of Fame.

THE SPEEDY dispatch of intelligence has been one of the objectives of the human race almost from the dawn of existence. Civilized and savage attacked it, and it must be admitted that the latter showed more ingenuity and skill. The yellow man, the red man and even the black man, all evolved simple but effective means of long-distance communication, while the white brother, after making some progress in the Greek and Roman eras, lost it all in the dark ages, and it was not until the 17th Century was drawing to a close that the semblance of a visual telegraph appeared in Europe, when Dr. Robert Hooke of England set up a semaphore line, while cooped up in Vienna in 1684 by the Turks.

But another century passed by without any attempt being made to apply Hooke's very simple invention, although in 1763 the Town Council of Liverpool made some effort toward speedy news, when it established a signal station at Bidston on the opposite side of the Mersey, to announce the arrival of ships off the mouth of the river.

Thirty years later came the French semaphore, devised by Clause Chappe when a school boy, with no knowledge of Hooke's machine. Twice the Paris mob tore down the poles, but when in 1793 the semaphore brought the news of a victory that very day over the Austrians, three hundred miles away, Chappe was hailed as a hero and made superintendent of telegraphs by the Convention. Within a few years all the principal ports and leading cities in France were in quick communication with Paris; and Germany, Italy and Russia had followed with the same system. But England held aloof, contenting itself with a shutter telegraph invented by Sir George Murray, which was used for more than twenty years. It was through the Murray telegraph that the news came of the arrival of Napoleon at Torbay, a month after Waterloo was sent to London, and the order returned denying the fallen warrior an asylum in England. Descriptions of Chappe's semaphore appeared in the Gentleman'sMagazine in September 1794 and that of Murray's shutter system in the same publication in January 1796. By 1825 semaphore telegraph was universal throughout the world, in fact the British used it on their warships up to within a few years ago, even after the adoption of the wireless, while Hooke's, Chappe's and Grout's device continues to be the most practical system for every railroad.

The Grout family claims an ancestry of Teutonic origin reaching back to the 10th century, one member of which, Baron Gross of Prussia, is said to have contributed to the invention of the magnetic telegraph.

The first of the family to reach the new world was Captain John Grout of England, who, settling in Watertown in 1640 on lands purchased from the Indians, married Sarah Cakeboard by whom he had eight children, the fifth, Jonathan Grout, born on August 1, 1658, being the ancestor of the subject of this sketch. The first Jonathan Grout married Mary Dix, and one of their five children, John Grout, born October 14, 1704, after uniting with Martha Boynton, moved to that part of Groton, Mass., that subsequently became Lunenburg. Their fourth child Jonathan Grout the second of the name, born July 23, 1737, cut quite a figure in Massachusetts, before, during and after the revolution. He served with the Colonial forces in the expedition to Lake Champlain in the French and Indian war, and brought back the dispatches announcing the capture of Crown Point. He was with Washington, with whom he enjoyed some acquaintance, in the siege of Boston, and returning to his home in Petersham, Mass., where he practiced law, helped to raise many companies of troops in northern Worcester County, and after the war was a member with Caleb Strong and Elbridge Gerry in the Massachusetts delegation to the first Congress. His wife was Sarah Page, a daughter of Governor Page of New Hampshire. He died in 1807 while attending court in Dover, N. H.

JONATHAN GROUT JR., the telegrapher, was born in his grandfather's house in Lunenburg, January 22, 1761. He attended Dartmouth College from which he graduated in 1787, with a degree of Master of Arts, and after studying law in his father's office in Petersham, moved to Belchertown, Mass., where he hung out his shingle in 1792. What turned him from legal to mechanical pursuits is not known, but it seems likely that he became interested in long-distance telegraphy through reading of the success of the systems in Europe in the two articles referred to in the Gentleman's Magazine, and impressed by the simplicity of Chappe's invention, obtained a patent in this country for a semaphore telegraph in 1800.

His reasons for selecting Vineyard Haven, or Holmes's Hole as it was known at the time, as his objective, was because the harbor on the north side of Martha's Vineyard was then and has been for many years since a key port not only for coastwise commerce, but for ships from both the West and East Indies, Europe and South America, bound for ports north. Right up to the opening of the Cape Cod canal less than twenty years ago, every newspaper on the Atlantic coast that maintained a shipping section carried full reports of arrivals, sailings and passings at Vineyard Haven. Grout started out by applying for and receiving permission to erect a pole on Fort Hill in Boston early in 1800 to be used "for a line of telegraphs from Martha's Vineyard to Boston, to be operated from hilltop to hilltop, sighting by telescope." The location, however, was not used for when the telegraph finally reached Boston, Grout found a more advantageous site on Orange St., afterward Washington St., out on Boston Neck.

A full year was necessary to set up the line, the route of which can easily be traced by reason of the fact that the designation "Telegraph Hill" still lingers round the summits of seven heights between Wood's Hole and Boston. There is a Telegraph Hill in West Falmouth, another in Pocasset, a third in Sandwich, a fourth in south Plymouth, a fifth in Duxbury, in what is known as the Millwood section, a sixth in Marshfield, while one of the streets near the top of Dorchester Heights in South Boston, still bears the name of Telegraph Street, which was given it when Grout made the summit one of his stations in 1801.

How Grout financed his somewhat considerable enterprise is not known, but it seems quite probable that he received some assistance from his father who is credited with owning forty thousand acres of land in Central New England about the time. Still it must have been no small task to locate the hills, cut paths to their summits, clear away the shrubbery, build huts and equip masts; and something more than personal persuasion to secure and teach an operating force, and maintain it even for a few hours each day, through six long winters, for Grout did not keep his line open in the summer owing to lack of patronage.

In the fall of 1801 the first long-distance telegraph in the country had been completed almost within sighting distance of Boston, and on October 24th, the Boston Gazette announced that:

A line of telegraphs has been completed from theVineyard to Cohasset. On October 21 informationof the arrival of the ship Mercury at the Vineyardfrom Sumatra was very expeditiously and correctlycommunicated, passing througheleven different stations. The linewill be extended to Boston.

It was an interesting coincidence that the first message transmitted concerned the God ofSpeed.

By early November Grout had his line working to Dorchester Heights where he had set up his thirteenth station on the site of the fortification that drove the British from Boston a quarter of a century before, and on Novem- ber 17th inserted the following advertisement in the New Eng- land Palladium:

TELEGRAPH

Information is hereby given tothe Public that the Subscriber inpursuance of a Patent which hehas obtained from the Government has erected a line of Telegraphs between Martha's Vineyard and Boston, adistance of 90 miles and has opened an office (forthe present) under the same roof where the telegraph in Boston stands, viz., 112 Orange St., and isready to convey correct intelligence reciprocallythrough said line.

Fees for Intelligence from the Vineyard are ratedaccording to a scale of reasonable proportions from$2.00 to $I00.00. To know more of which please apply as above from S to IT A.M. and from 6 to 8 P.M.

Grout's line, which was actually a trifle less than eighty miles, was routed as follows, using the designations of the hills as they appear on maps of today:

West Chop to Quissett Hill Wood's Hole 6 miles Wood's Hole to Telegraph Hill West Falmouth 5 miles West Falmouth to Telegraph Hill Pocasset 7 miles Pocasset to Telegraph Hill Sandwich 6 miles Sandwich to Monument Hill Cedarville 5 miles Cedarville to Telegraph Hill South Plymouth 5 miles South Plymouth to Pilgrim Hill Chiltonville 4 miles Chiltonville to Great Captain's Hill Duxbury 6 miles Duxbury to Telegraph Hill Millwood 4 miles Millwood to Telegraph Hill Marshfield 5 miles Marshfield to Greenbush Hill Scituate 5 miles Scituate to Turkey Hill Cohasset 7 miles Cohasset to Great Hill Weymouth 5 miles Weymouth to Telegraph Hill South Boston 7 miles South Boston to Orange St. Boston 2 miles 79 miles

ALTHOUGH HIS telegraph was of course for the exelusive use of his subscribers, Grout naturally found some publicity necessary, and dealt out to the press certain items which had gone to his customers several days before, and even then were considerably ahead of despatches received from the Vineyard by ordinary means. One of the earliest to appear in print and one in which he must have taken considerable pride and satisfaction, to say nothing of astonishing a staid old town like Boston, concerned the arrival of the ship Holland in November 1801 at the Vineyard. Within an hour after the ship had been reported by telegraph her owner in Boston at 3:40 P.M. sent back an order to the commander, directing him to proceed to New York. The skipper of the Holland being naturally somewhat skeptical over the genuineness of the order, received in so short a time after he had reached the vineyard, sent the following message at 3:49 P.M.: "I understand you to say that ship Holland now at anchor here must sail for New York."

The owner immediately replied: "Yes, you understand me right."

The departure of the Holland for New York was reported the next day by the telegraph.

Several other items from the Vineyard were vouchsafed the newspapers but after awhile Grout shut down on specific information for the press, although he did announce in the Columbian Centinel on February 4, 1802, that two vessels were ashore at the Vineyard. The newspapers had the satisfaction a few days later of noting the arrival of a ship in Boston that had passed the Vineyard three days before, but which the telegraph had failed to report owing to unfavorable transmitting conditions, for Grout's line like every visual telegraph went out of commission in thick weather.

For several winters Grout catered to Salem shipping interests in the hope of securing sufficient support in that town to enable him to extend his line down the north shore of Massachusetts Bay and perhaps on to Portland, and at one time notified his agent at the Vineyard, "not to designate any arrivals unless the vessels belong to Salem or to subscribers, whose names I have given you."

He missed a chance to gain Salem favor when his line failed late in February to send up from Sandwich the news of the loss of three Salem vessels, Brutus, Volusia and Ulysses at the tip end of Cape Cod in the storm of February 23, 1802. The wreck must have been known several days later all over the Cape, but few if any items of news originating along the line seems to have been carried by the telegraph at any time, so the report of the disaster did not reach Salem until early in March.

Grout made no effort to maintain his line in the summer season, as has been said, probably for the reason that merchants had less anxiety regarding the safety of their argosies at that time of the year, and were content to receive news by the old methods at little or no cost, even though it might be two or three days late. On May 13, 1802, Grout therefore announced that the "operation of the Telegraph from Boston to Martha's Vineyard had been adjourned until September 20."

The service was resumed in October and maintained throughout the following winter apparently with some success, for very few news items appeared in the local newspapers. After another summer's lapse the Telegraph went into commission again in the fall of 1803 and while its efficiency was shown by the speedy handling of an order directing the ship Commerce to proceed to New York, business apparently began to decline, and between January and April 1804 he gave out for publication several items stating that the "Proprietor of the Telegraph has news of vessels at the Vineyard" but refusing to divulge their names.

Seeking closer touch with his subscribers, Grout changed his office early in 1804 from Orange St. to 75 State St. where he made an ambitious effort to broaden his news service by publishing a Poster offering to sell "First Intelligence" of any kind of a vessel bound from any part of the world in a graduated scale of rates, based on the size or rig of the craft and the location of the port from which she had sailed. A copy of this Poster is in the archives of the American Antequarian Society at Worcester, Mass. The charge for a sloop or schooner from the West Indies was $10; for the same type of vessel from Europe it was $l5, and for one from the far east $25, with half as much again for brigs and snows and nearly double for barks and ships. Grout evidently expected that much of this information would be obtained by his agent at the Vineyard, for in his Poster he calls attention to his telegraph line. In 1805 he attempted to supplement the service by giving "First Intelligence" of vessels from Chesapeake Bay and ports farther south, and the next year announced rates for non-subscribers to his Telegraph. Had he been able to sell his news to a combination of newspapers, he would have antedated cooperative news service forty years before it was adopted by the first Associated Press.

Late in the fall of 1806 Grout appointed Joseph May of the Marine Insurance Company of Boston to receive subscriptions and early in 1807 designated Edward Renouf of the Columbian Centinel to handle dispatches from the Vineyard. The last message to appear in a Boston newspaper was that under date of April 24, 1807, which may be regarded as the close of the first effort to maintain a telegraph in this country. Nearly seventy years rolled by before Vineyard Haven was again in telegraphic communication with the mainland, so its shipping news lapsed back to conditions which prevailed before Grout's ambitious enterprise.

Grout subsequently removed to Philadelphia where he embraced the Swedenborgian religion and devoted the remainder of his life to literary and scientific pursuits, in both of which he is said to have been eminent. In the Philadelphia directory of 1821 his name appears as the "Inventor of a Universal Grammar" with a residence at 1 Carpenter Court, while in 1825 the directory gives his address as the Shakespeare Building, South 6th St. He died March 12, 1825, credited with being a professor of Grammar with no mention of his telegraphic achievements, but nevertheless "a very respectable old gent."

Jonathan Grout's SemaphoreTelegraph Line

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Sports

SportsFOLLOWING THE BIG GREEN TEAMS

June 1933 -

Article

ArticleHANOVER BROWSING

June 1933 By Rees Higgs Bowen -

Class Notes

Class NotesClass of 1930

June 1933 By Albert I. Dickerson -

Class Notes

Class NotesClass of IQ9 1

June 1933 By Jack R. Warwick -

Article

ArticleSecretaries Convene

June 1933 -

Article

ArticleTHE UNDERGRADUATE CHAIR

June 1933 By S. H. Silverman '34