THE CHARACTER OF and the changes in the student-faculty relationships at Dartmouth since iB6O have been of great interest to me while making a study this year of Dartmouth student life since the Civil War. Obviously it was not to be expected that traits of undergraduate behavior would remain unchanged through the years; nor yet was it to be anticipated that any traits would show such an interesting transition as has been evidenced by the attitudes of the undergraduates toward the faculty and by the expression of these attitudes.

In the very earliest days the College was considered as in loco parentis. Its primary function was that of a moralist and an ethical teacher. The development- of the undergraduate mind was incidental to the major problem of caring for the undergraduate character.

It is said that Asa Dodge Smith, while President of the College, made it a point to interview personally every undergraduate at some time during the college course in order that he might have an intimate, paternal chat concerning the religious beliefs of each of his foster children. Today it is wholly impossible to conceive of a college president making it his personal function thus to survey and correct the ethical and theological views of each and every member of the student body. Yet the personal interview was the least offensive of the many methods employed in the early days. Gum shoe detective activities on the part of the faculty were frequently common and the use of disguises was not entirely unknown. Such preoccupation with the way in which the undergraduate employed his time is not completely understandable now except in the light of the function of the college as a great foster parent in charge of student morality.

Another device adopted by the faculty to further their contact with the student body was the setting aside of one night a week during which faculty open-houses were held. On these occasions all students were invited to visit the faculty members at their homes and come more closely under the benign influence of righteous men leading exemplary lives. In spite of this opportunity, however, calling on faculty members was only an infrequent practice among the undergraduates.

The attitude of the students themselves toward the members of the faculty in the early days was a curious and paradoxical Mixture of respect and contempt. The respect was evidenced by the common couresies of the street. At that time it was the custom to stand at attention ten paces away from a Passing faculty member; and if the resident of the College should pass by, it was the duty of the undergraduates to stand at fifteen paces and doff the hat. These customs were rigidly adhered to for the student keenly felt the reverence which he displayed. The members of the faculty were considered as belonging to an entirely different sphere from that of the youths: they were veritable Gods dwelling upon an academic Olympus. As such, it is true, they were austere creatures, rarely inspiring love—only respect and often fear. Although familiarity was indeed a sacrilege, the unnatural and aloof relationship between the two groups frequently strained reverence to the breaking point and resulted in both contempt and hostility. Here as everywhere else, however, the factor of the individual personalities involved on both sides was tremendously important in determining the relationship.

Two of the most prominent manifestations of student hostility were the old Dartmouth traditions of "horning" and "wooding up." "Horning" was a ruthless type of serenade invented by the students and considered as an inalienable right. Any faculty member who was so unfortunate as to incur undergraduate enmity was subjected to it. The mechanics of the serenade were distressingly simple. The undergraduates, sheltered by nocturnal darkness, would gather about the residence of the offending tutor and aided by a wide variety of horns, kettles, and drums, would endeavor to make lite miserable for the occupant. In this they were eminently successful. Many is the Dartmouth alumnus who vividly recalls the howling delight of; the vindictive students as the wrathful victim of the tin symphony appeared on the porch of his home in an effort to quell the crescendo of the clamor.

The other outstanding example of student hostility, "wooding up," was considerably less offensive but at times equally as disconcerting as "horning." Should any professor ever be so unwise as to indulge in stale jokes or should he attempt to polish the professorial ego, the response was instantaneous. A deafening stamping of feet was certain to greet such a display. From every part of the room shuffling and scraping boots produced such a din that all fforts to proceed with the class were hopeless, no matter how loud the instructor bellowed in the effort to stifle the uproar by his own vociferousness. "Wooding up" was the popular indoor game of the time and lasted as such till well into the twentieth century. It left in its wake many shattered tempers and broken classes, as well as provoking memories.

IT is interesting to speculate today why the studentsfgsjiould have indulged in what impress us questionable activities. Outside of the universal desire of human nature to see the great removed from their pedestal—a desire that is gratified when pomposity slips on banana peels or when tall hats are effectively removed by snow balls—there are several definite reasons. Outstanding among these may be listed the rural background of the students and the personality, defects of the faculty. Often the -tutors were severe, officious, or inexpert in dealing with the student mentality. One famous old professor who was subsequently soundly "horned" became too tired to learn the names of his students so he devised the ingenious plan of numbering them. This might have worked very well if the students had not spoiled his plan by rebelling against classification as mere digits. Possibly the procedure smacked too much of the penitentiary!

Other examples of the inexpertness of the faculty in handling student matters are many. One of them, the consequences of which were amusing rather than unhappy, was the faculty edict of 1869 forbidding the sophomore class to indulge in the sacred tradition of burying Mathematics. This edict was prompted by the belief that the burial rites, an elaborate affair, were becoming too great a travesty on the funeral ceremony. The sophomores of that year were not one whit daunted by the decree. Upon concluding their study of "math" they went ahead with their detailed plans for the ceremony—the only difference being that a cremation was substituted for the burial, a fact which left them technically unpunishable.

THE "BURIAL" AS conducted by the class of 1886 may be taken as typical of the age old ceremony. Preparations were made weeks in advance as programs had to be printed, speeches prepared, and costumes secured. On the chosen night a huge pyre was erected on the campus whither a weird procession wended its way. At the head of the procession, in costume and mounted on horses, was a Head Devil with four members of his cabinet. The Hartford band followed those grotesque figures and added its bit to the general clamor. Behind the band came the priests who were to conduct the ritual of the ceremony: the Pontifex Maximus and the various Pontifices, all in priestly regalia. Then in a body came the class proper escorting the orators of the occasion whose studied eloquence and eulogies of the lamented deceased were the feature of the ceremony. The corpse, itself Mathematicus—a bier loaded with books and drawn by a four horse team brought up the very rear of the motley array. Upon arriving at the pyre a long ritual was carried out and finally the torch applied. Adjournment then to Bed Bug Alley in Dartmouth Hall for "lemonade" was inevitable.

A further reason for hostile contempt was the mutual lack of understanding between the two groups. The undergraduate was a young barbarian, an uncouth animal, as he still is in many ways today, and the clash of attitudes was certain to result in friction with the faculty. Then too there were no organized athletic activities in the very earliest days. The undergraduate was largely left to his own devices for working off excess energy, and surely it is not surprising that "horning" should appeal to the youthful mind as an excellent means of garnering exercise—both of lung and limb. Today, as a general rule, undergraduate energy is directed into more harmless channels. A further consideration is the fact that then there were no elective subjects and all of the students were subjected to the same courses and the same professors. Thus grievances instead of being confined to a relative few were common ones cherished by a united class. Such a multiplication of unrest was certain to have its effect.

IN MORE RECENT years the function of the faculty and the College has been conceived not as primarily that of an ethical parent; but rather as that of an understanding teacher endeavoring to develop the student physically, and mentally as well as morally.

This change in function has been made possible by a change in the type of faculty member. No longer are they all ethical philosophers moving about in a sphere of their own far above the ken of the average student; but rather they are now sincere human beings meeting the student on his own level. Today there is not a disparity but rather a similarity of interests between the two groups. The faculty has become companionable with the student body insofar as it is able to do so in view of the great handicap of the size of both groups. The contacts are no longer limited to the classroom and occasional fraternal meetings; no longer does the artificial atmosphere of an open house, where the student called as one would call on a disciple of God, prevail. Today it is the friendly contact on the squash court and the street, at athletic contests and the movies, as well as in the classroom and the home, that cements the mutual respect and the mutual understanding.

Mathematical Tombstone Beneath it lie the text books of 1884.

Watering Trough on the Corner Was Scene of Rallies and Speech-making

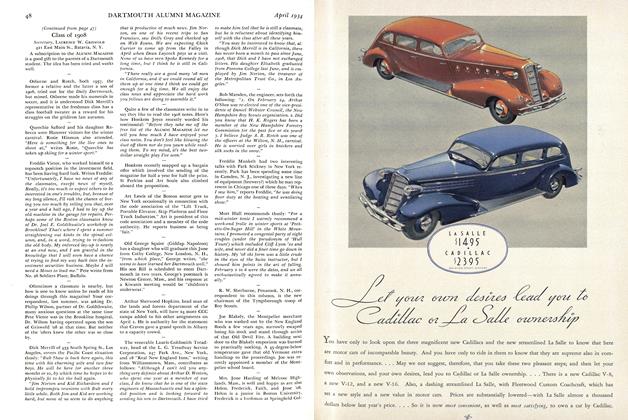

Senior Fellow

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Class Notes

Class NotesClass of 1918

April 1934 By Allan C. Gottschaldt -

Article

ArticleHANOVER BROWSING

April 1934 By Rees H. Bowen -

Class Notes

Class NotesClass of 1910

April 1934 By Harold P. Hinman -

Class Notes

Class NotesClass of 1908

April 1934 By Laurence W. Griswold -

Class Notes

Class NotesClass of 1930

April 1934 By Albert I. Dickerson -

Class Notes

Class NotesClass of 1923

April 1934 By John C. Allen