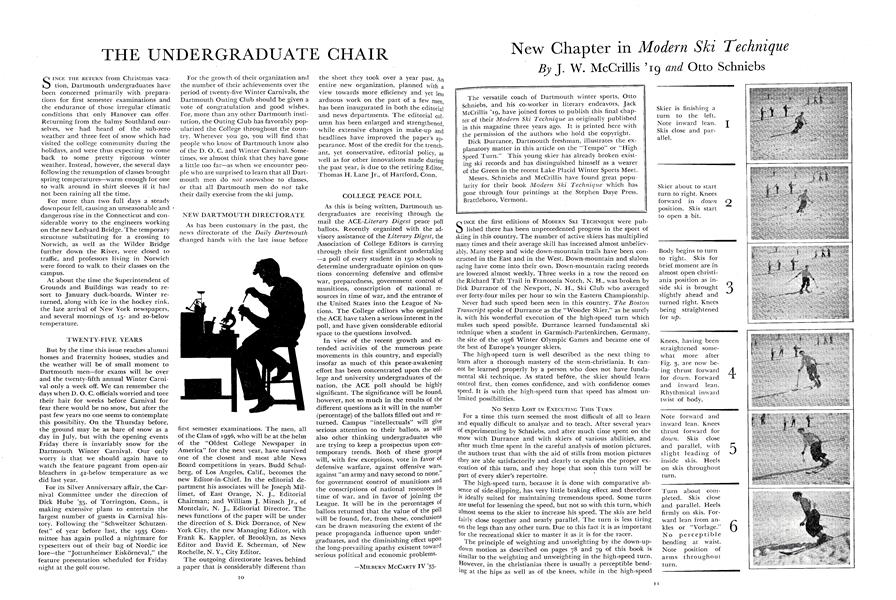

The versatile coach of Dartmouth winter sports, Otto Schniebs, and his co-worker in literary endeavors, Jack McCrillis '19, have joined forces to publish this final chapter of their Modern Ski Technique as originally published in this magazine three years ago. It is printed here with the permission of the authors who hold the copyright.

Dick Durrance, Dartmouth freshman, illustrates the explanatory matter in this article on the "Tempo" or "High Speed Turn." This young skier has already broken existing ski records and has distinguished himself as a wearer of the Green in the recent Lake Placid Winter Sports Meet.

Messrs. Sctiniebs and McCrillis have found great popularity for their book Modem Ski Technique which has gone through four printings at the Stephen Daye Press, Brattleboro, Vermont.

SINCE the first editions of MODERN SKI TECHNIQUE were published there has been unprecedented progress in the sport of skiing in this country. The number of active skiers has multiplied many times and their average skill has increased almost unbelievably. Many steep and wide down-mountain trails have been constructed in the East and in the West. Down-mountain and slalom racing have come into their own. Down-mountain racing records are lowered almost weekly. Three weeks in a row the record on the Richard Taft Trail in Franconia Notch, N. H„ was broken by Dick Durrance of the Newport, N. H., Ski Club who averaged over forty-four miles per hour to win the Eastern Championship.

Never had such speed been seen in this country. The BostonTranscript spoke of Durrance as the "Wonder Skier," as he surely is, with his wonderful execution of the high-speed turn which makes such speed possible. Durrance learned fundamental ski technique when a student in Garmisch-Partenkirchen, Germany, the site of the 1936 Winter Olympic Games and became one of the best of Europe's younger skiers.

The high-speed turn is well described as the next thing to learn after a thorough mastery of the stem-christiania. It cannot be learned properly by a person who does not have fundamental ski technique. As stated before, the skier should learn control first, then comes confidence, and with confidence comes speed. It is with the high-speed turn that speed has almost unlimited possibilities.

No SPEED LOST IN EXECUTING THIS TURN

For a time this turn seemed the most difficult of all to learn and equally difficult to analyze and to teach. After several years of experimenting by Schniebs, and after much time spent on the snow with Durrance and with skiers of various abilities, and after much time spent in the careful analysis of motion pictures, the authors trust that with the aid of stills from motion pictures they are able satisfactorily and clearly to explain the proper execution of this turn, and they hope that soon this turn will be part of every skier's repertoire.

The high-speed turn, because it is done with comparative absence of side-slipping, has very little braking effect and therefore is ideally suited for maintaining tremendous speed. Some turns are useful for lessening the speed, but not so with this turn, which almost seems to the skier to increase his speed. The skis are held fairly close together and nearly parallel. The turn is less tiring on the legs than any other turn. Due to this fact it is as important for the recreational skier to master it as it is for the racer.

The principle of weighting and unweighting by the down-updown motion as described on pages 78 and 79 of this book is similar to the weighting and unweighting in the high-speed turn. However, in the christianias there is usually a perceptible bending at the hips as well as of the knees, while in the high-speed turn the down-up-down motion is accomplished almost entirely by the bending of the knees and there is very little, if any, bending at the hips. But weighting and unweighting is the essence of the turn, and is accomplished by the knees.

The initial DOWN may indeed be so slight and so brief as to be scarcely discernible, but the beginner will do well to make a pronounced initial DOWN by the bending of the knees. As the knees are straightened for the UP there is a slight rhythmical twist of the body toward the inside of the turn with a slight leading of the inside ski and a pronounced leaning far forward from the ankles. There is little or no bending at the hips. The knees are thrust way forward for the second DOWN. The pronounced forward leaning from the ankles or "Vorlage" with little or no bending at the hips and comparative absence of sideslipping are characteristics of the turn which distinguish it from the christianias. The skis are kept close together and nearly parallel throughout the turn. It is chiefly the forward and inward lean, which may be well described as a "dive," together with a rhythmical twisting of the body and the changing of weight by the down-up-down of the knees which causes the turning.

The turn is especially adapted for long radius turns. The turn cannot be done properly without considerable speed. The greater the speed and the sharper the turn the more must the skier lean inward to counteract the centrifugal force which tends to throw him outward. As the skis are close together and as the center of gravity is high the arms are extended somewhat to help the sidewise balance.

The high-speed turn is most suitable for light snow, but can well be done on hard packed snow if the skis have metal or other hard edges.

Under favorable conditions the typical high-speed turn has an initial DOWN, followed by the UP, and a second DOWN with knees far forward throughout the remainder of the turn; the skis are close together and nearly parallel throughout. However, the initial DOWN may be very slight, and speed, radius of turn, snow conditions, or terrain may cause the skis to separate slightly, or one ski may be stemmed somewhat or opened slightly as in the open christiania, or the turn may be jerked. The sidewise balance in this turn is not as stable as in some other turns and it is often necessary, because of change in speed, snow conditions, or terrain to quickly and automatically shift from this to some other turn, in the manner similar to that already described in Chapter VI.

Down-mountain or slalom racers will want to master the highspeed turn. Because of the comparatively little side-slipping, this turn retards the speed less than others and—equally importantthis turn tires the legs less than others. Those who ski for recreation will also want to master the high-speed turn to add to the ease of down-mountain descents and to find new thrills which will come as they acquire more speed with less expenditure of muscular energy.

NOTE: The high-speed turn is now shown in the 16 mm. motion picture "Modern Ski Technique" which is mentioned on page 96 of the book.

Skier is finishing a turn to the left. Note inward lean. Skis close and par- allel.

Skier about to start turn to right. Knees forward in down position. Skis start to open a bit.

Body begins to turn to right. Skis for brief moment are in almost open christi- ania position as in- side ski is brought -4 slightly ahead and turned right. Knees being straightened for up.

Knees, having been straightened some- what more after Fig. 3, are now be- ing thrust forward A for down. Forward and inward lean. Rhythmical inward twist of body.

Note forward and inward lean. Knees thrust forward for down. Skis close and parallel, with PI slight leading of inside skis. Heels on skis throughout turn.

Turn about com- pleted. Skis close and parallel. Heels firmly on skis. For- ward lean from an- kles or "Vorlage." 0 No perceptible bending at waist. Note position of arms throughout turn.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Article

ArticleHANOVER BROWSING

February 1935 By Herbert F. West '22 -

Article

ArticleForgotten Dartmouth Men

February 1935 By Prof. H. F. West '22 -

Class Notes

Class NotesClass of 1930

February 1935 By Albert I. Dickerson -

Class Notes

Class NotesClass of 1908

February 1935 By L. W. Griswold -

Article

ArticleTHE DARTMOUTH EYE CLINIC

February 1935 -

Class Notes

Class NotesClass of 1934

February 1935 By Mariin J. Dwyer Jr.

Article

-

Article

ArticleADDRESS OF PRESIDENT ERNEST MARTIN HOPKINS AT THE OPENING OF DARTMOUTH COLLEGE, SEPTEMBER 23, 1920

November 1920 -

Article

ArticleFIFTY BOOKS INCREASE KENERSON COLLECTION

December, 1922 -

Article

ArticleDr. Wheelock's Almanack

January 1935 -

Article

ArticleFull name: Sheba

MAY 1997 -

Article

ArticleA Student on His Own

JUNE 1930 By H. S. Embree -

Article

ArticleWith the Outing Club

JANUARY 1929 By R. B. Sanders