THE CURRICULUM at Dartmouth, or in fact anywhere, is far from being a simple thing. It is at this moment a complexity in the same degree that almost every other function of American life has become complex. The day is long since past when a man came to Dartmouth to learn certain specific things, to gain enough knowledge from the classics for example to enable him to fill a speech with Virgilian quotations, to resolve into undemanding definitely and forcefully the relation between a well defined God and the universe, to pick up enough "Mathematicks" to enable him to go round his farm or estate with a surveyor's outfit and know just where the boundaries lay. College in its simplest days possessed a curriculum that was simple, definite and pointed. And it may be said that the learning of that day was simple, definite and pointed. In the days in which these things were taught they were in themselves sufficient to assure a young man of a place in society, of giving him the mental instruments whereby he could place himself in relation to ihe rest of the world and the universe.

But in our day the astounding complexity of life, the new conceptions of religion, the growth of science, and the formation of a new society which is in itself a complexity—these are but a few of the influences at work upon the curriculum in the college. For the curriculum is designed today as it was in a simpler and less sophisticated age to give a man the instruments of mentality whereby he can find himself and make a place for himself in the world in which he lives. President Hopkins in a talk to some members of the faculty a few years ago recalled a conversation he had with an alumnus who used to walk back and forth to the College at the beginnings and ends of terms; that alumnus, alone, and in the starry night had the opportunity to meet problems and think them out by himself. But men don't walk to College any more, and they are seldom alone, and the opportunity to think out these essential things alone comes less and less.

HERE AND THERE in larger colleges, in smaller colleges too, the emphasis is slowly shifting from a wide-flung curriculum to one which centers in the study of the environment and the activities of men. These social sciences, so called, including among others, history, economics, sociology, and political science, dealing with the most common relationships of men, seem to answer most closely the demands of a complex civilization in which each student must live after he leaves his college. For the humanities, the classics, literature, art, music, there is no lessened demand. These will always be wanted and always be chosen. But the subjects which deal with the elements of the complex world in which we live are so necessary, so vital, and indeed on the part of the students so desirable, that institutions of learning have been seeing them grow until they now far outnumber in enrollment the older and more cultural subjects.

The curriculum at Dartmouth has been evolving slowly in this direction for many years. And now a faculty committee is at work studying the effects of different types of courses of study at other colleges. It is now quite generally conceded that the "learning for learning's sake" type of student in the old sense of the phrase is at a minimum in most colleges. Many of them are genuinely interested in broad scholarship and want to get some survey of the world they live in, of the men they will work with, and to have some training in the world of thinking so that they may apply themselves intelligently and with some sense of direction in the complexity of things.

And with this the College should hope that they will possess poise and the ability to study the world and their environment as objectively as did the boys who learned to think in the days when it was possible to be alone. The College should want its students to acquire the ability which Prof. Stearns Morse attributes to the late Professor MacKaye: "His mind was both subtle and relentlessly logical .... it cut through to the roots of things "

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Article

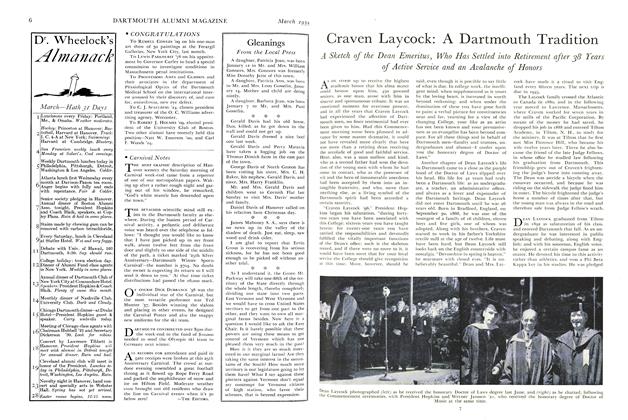

ArticleGraven Laycock: A Dartmouth Tradition

March 1935 By C. E. W. '30 -

Article

ArticleHANOVER BROWSING

March 1935 By Herbert F. West '22 -

Class Notes

Class NotesClass of 1914

March 1935 By C. Edward Leech -

Class Notes

Class NotesClass of 1918

March 1935 By Allan C. Gottschaldt -

Article

ArticleTwenty-Five Years Ago

March 1935 By Hap Hinman '10 -

Class Notes

Class NotesClass of 1934

March 1935 By Martin J. Dwyer Jr.

Article

-

Article

ArticlePacific Coast Meetings

March 1946 -

Article

ArticleTom O'Connell '50 Wins Alexander Meiklejohn Award

JUNE 1973 -

Article

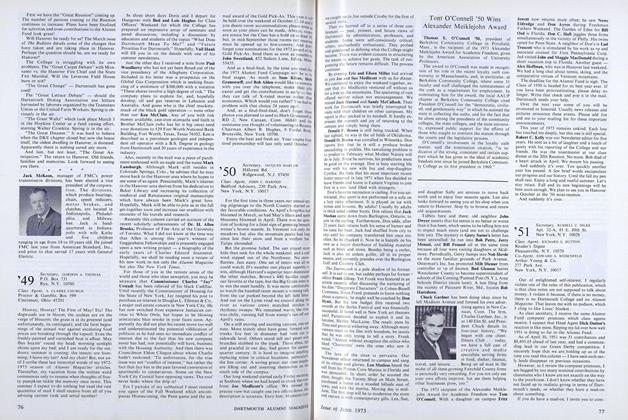

ArticleDartmouth Signs $2 million Computer Contract

DECEMBER 1983 -

Article

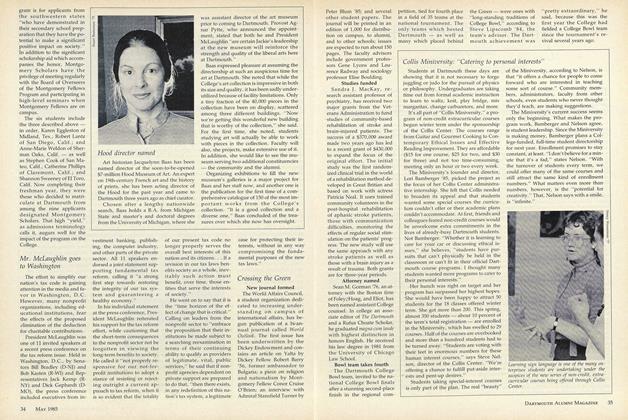

ArticleHood Director Named

MAY 1985 -

Article

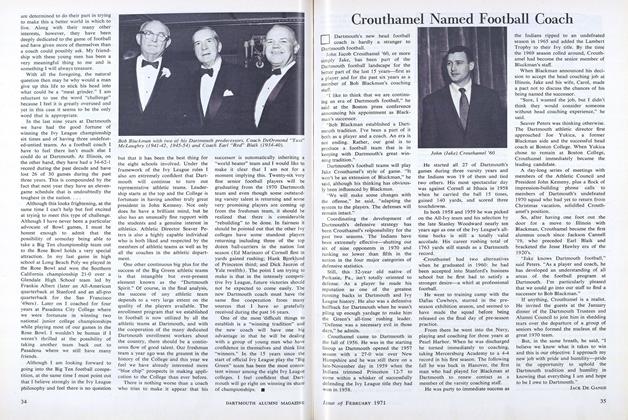

ArticleCrouthamel Named Football Coach

FEBRUARY 1971 By JACK DE GANGE -

Article

ArticleEndowed Professorships

JUNE 1973 By RICHARD E. STOIBER '32