Department of Geology

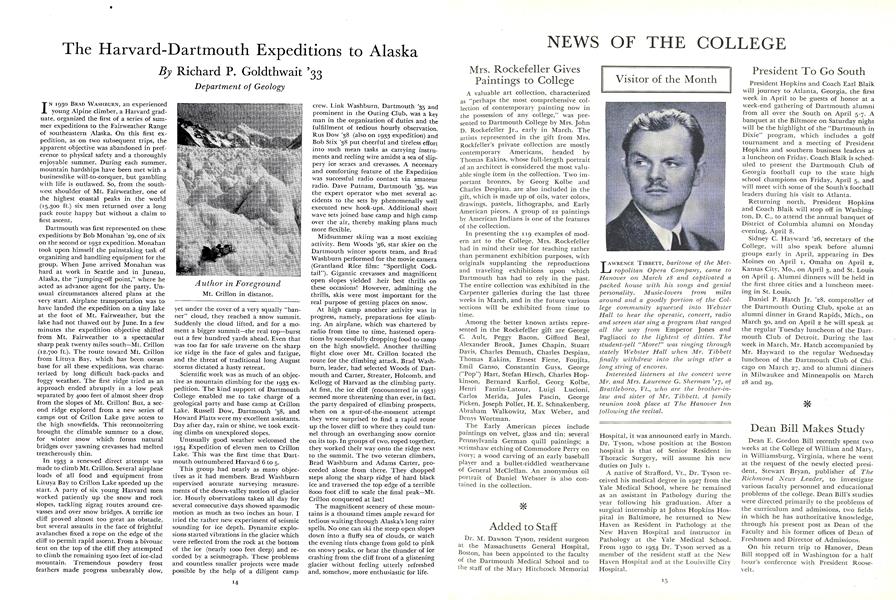

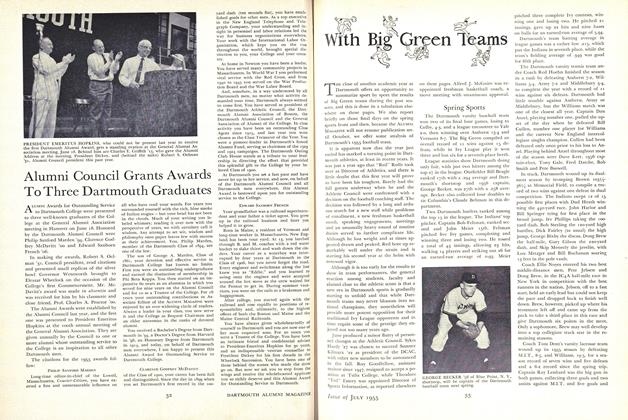

IN 1930 BRAD WASHBURN, an experienced young Alpine climber, a Harvard graduate, organized the first of a series of summer expeditions to the Fairweather Range of southeastern Alaska. On this first expedition, as on two subsequent trips, the apparent objective was abandoned in preference to physical safety and a thoroughly enjoyable summer. During each summer, mountain hardships have been met with a businesslike will-to-conquer, but gambling with life is outlawed. So, from the southwest shoulder of Mt. Fairweather, one of the highest coastal peaks in the world (15,300 ft.) six men returned over a long pack route happy but without a claim to first ascent.

Dartmouth was first represented on these expeditions by Bob Monahan '29, one of six on the second or 1932 expedition. Monahan took upon himself the painstaking task of organizing and handling equipment for the group. When June arrived Monahan was hard at work in Seattle and in Juneau, Alaska, the "jumping-off point," where he acted as advance agent for the party. Unusual circumstances altered plans at the very start. Airplane transportation was to have landed the expedition on a tiny lake at the foot of Mt. Fairweather, but the lake had not thawed out by June. In a few minutes the expedition objective shifted from Mt. Fairweather to a spectacular sharp peak twenty miles south Mt. Crillon (12,700 ft.). The route toward Mt. Crillon from Lituya Bay, which has been ocean base for all these expeditions, was characterized by long difficult back-packs and foggy weather. The first ridge tried as an approach ended abruptly in a low peak separated by 4000 feet of almost sheer drop from the slopes of Mt. Crillon! But, a second ridge explored from a new series of camps out of Crillon Lake gave access to the high snowfields. This reconnoitering brought the climable summer to a close, for winter snow which forms natural bridges over yawning crevasses had melted treacherously thin.

In 1933 a renewed direct attempt was made to climb Mt. Crillon. Several airplane loads of all food and equipment from Lituya Bay to Crillon Lake speeded up the start. A party of six young Harvard men worked patiently up the snow and rock slopes, tackling zigzag routes around crevasses and over snow bridges. A terrific ice cliff proved almost too great an obstacle, but several assaults in the face of frightful avalanches fixed a rope on the edge of the cliff to permit rapid ascent. From a bivouac tent on the top of the cliff they attempted to climb the remaining 2500 feet of ice-clad mountain. Tremendous powdery frost feathers made progress unbearably slow, yet under the cover of a very squally "banner" cloud, they reached a snow summit. Suddenly the cloud lifted, and for a moment a bigger summit the real top burst out a few hundred yards ahead. Even that was too far for safe traverse on the sharp ice ridge in the face of gales and fatigue, and the threat of traditional long August storms dictated a hasty retreat.

Scientific work was as much of an objective as mountain climbing for the 1933 expedition. The kind support of Dartmouth College enabled me to take charge of a geological party and base camp at Crillon Lake. Russell Dow, Dartmouth '38, and Howard Platts were my excellent assistants. Day after day, rain or shine, we took exciting climbs on unexplored slopes.

Unusually good weather welcomed the 1934 Expedition of eleven men to Crillon Lake. This was the first time that Dartmouth outnumbered Harvard 6 to 5.

This group had nearly as many objectives as it had members. Brad Washburn supervised accurate surveying measurements of the down-valley motion of glacier ice. Hourly observations taken all day for several consecutive days showed spasmodic motion as much as two inches an hour. I tried the rather new experiment of seismic sounding for ice depth. Dynamite explosions started vibrations in the glacier which were reflected from the rock at the bottom of the ice (nearly 1000 feet deep) and recorded by a seismograph. These problems and countless smaller projects were made possible by the help of a diligent camp crew. Link Washburn, Dartmouth '35 and prominent in the Outing Club, was a key man in the organization of duties and the fulfillment of tedious hourly observation. Rus Dow '38 (also on 1933 expedition) and Bob Stix '38 put cheerful and tireless effort into such mean tasks as carrying instruments and reeling wire amidst a sea of slippery ice seracs and crevasses. A necessary and comforting feature of the Expedition was successful radio contact via amateur radio. Dave Putnam, Dartmouth '35, was the expert operator who met several accidents to the sets by phenomenally well executed new hook-ups. Additional short wave sets joined base camp and high camp over the air, thereby making plans much more flexible.

Midsummer skiing was a most exciting activity. Bern Woods '36, star skier on the Dartmouth winter sports team, and Brad Washburn performed for the movie camera (Grantland Rice film: "Sportlight Cocktail"). Gigantic crevasses and magnificent open slopes yielded .heir best thrills on these occasions! However, admitting the thrills, skis were most important for the real purpose of getting places on snow.

At high camp another activity was in progress, namely, preparations for climbing. An airplane, which was chartered by radio from time to time, hastened operations by successfully dropping food to camp on the high snowfield. Another thrilling flight close over Mt. Crillon located the route for the climbing attack. Brad Washburn, leader, had selected Woods of Dartmouth and Carter, Streater, Holcomb, and Kellogg of Harvard as the climbing party. At first, the ice cliff (encountered in 1933) seemed more threatening than ever, in fact, the party despaired of climbing prospects, when on a spur-of-the-moment attempt they were surprised to find a rapid route up the lower cliff to where they could tunnel through an overhanging snow cornice on its top. In groups of two, roped together, they worked their way onto the ridge next to the summit. The two veteran climbers, Brad Washburn and Adams Carter, proceeded alone from there. They chopped steps along the sharp ridge of hard black ice and traversed the top edge of a terrible 8000 foot cliff to scale the final peak Mt. Crillon conquered at last!

The magnificent scenery of these mountains is a thousand times ample reward for tedious waiting through Alaska's long rainy spells. No one can ski the steep open slopes down into a fluffy sea of clouds, or watch the evening tints change from gold to pink on snowy peaks, or hear the thunder of ice crashing from the cliff front of a glistening glacier without feeling utterly refreshed and, somehow, more enthusiastic for life.

Author in Foreground Mt. Crillon in distance.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Article

ArticleHANOVER BROWSING

April 1935 By Herbert F. West '22 -

Article

ArticleSTABILIZATION BY SPECIE PAYMENTS

April 1935 By Edward Tuck '62 -

Class Notes

Class NotesClass of 1908

April 1935 By L. W. Griswold -

Class Notes

Class NotesClass of 1910

April 1935 By Harold P. Hinman -

Class Notes

Class NotesClass of 1918

April 1935 By Allan C. Gottschaldt -

Class Notes

Class NotesClass of 1929

April 1935 By F. William Andres

Article

-

Article

ArticleCAMPUS NOTES

November 1920 -

Article

ArticleFaculty Publications

March 1936 -

Article

ArticleAlumni Council Grants Awards To Three Dartmouth Graduates

July 1955 -

Article

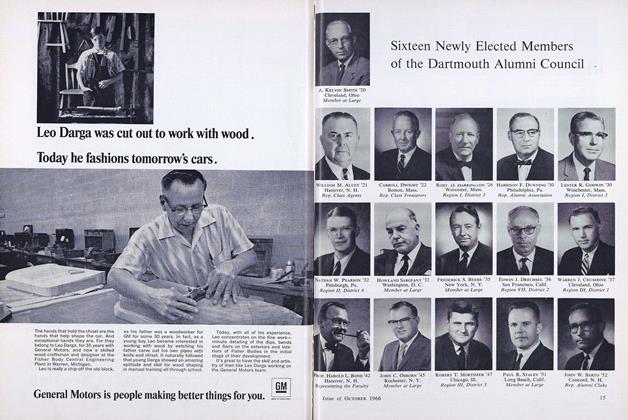

ArticleSixteen Newly Elected Members of the Dartmouth Alumni Council

OCTOBER 1966 -

Article

Article99 Rocks

June 1994 -

Article

ArticleTHE SPIRIT OF '21

October 1941 By GEORGE L. FROST